Donroe Doctrine: How Trump is enforcing his will

Following the intervention in Venezuela, the US president feels increasingly empowered to act without restraint toward other governments

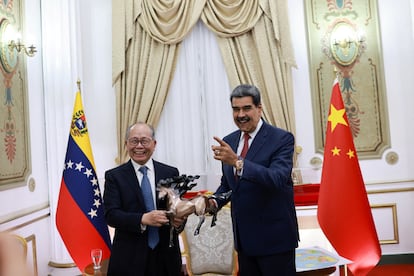

The scene in the East Room of the White House last Friday was almost like something out of a medieval court. At the center was an emperor — U.S. President Donald Trump — euphoric after his country’s military operation in which U.S. forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in Caracas, and surrounded by his top advisers. Around him were executives from the major multinational oil companies, who had come from around the world to pay homage and vie for a piece of Venezuela’s energy sector.

“This is historic,” said U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio. “A magnificent operation,” congratulated his vice president, J.D. Vance. “You’ve given hope to the people of Venezuela,” declared Ryan Lance of ConocoPhillips. “Thank you for what you did,” said Bryan Sheffield of Parsley Energy

Following the attack in Caracas, Trump is elated. What he sees as an unqualified success — the capture of the Venezuelan president without U.S. casualties in what resembled a blockbuster movie operation — vindicates his worldview. It is a vision in which his country, and especially he himself, enjoy a carte blanche to act as they wish, to coerce other governments, exploit natural resources, and not have to answer to international law. A virtually unlimited global power in which, according to one of his favorite metaphors, he holds all the cards.

Emboldened by an action that has diverted public attention away from scandals such as the one involving financier Jeffrey Epstein, Trump is now turning to more bellicose rhetoric to threaten further interventions. While predicting that changes in Venezuela will hasten the fall of Cuba’s communist regime, he has pointed to ground attacks against drug cartels “that are running Mexico.” Before his Wednesday call with Colombian President Gustavo Petro, aimed at a fragile truce, he warned the allied leader to “watch his ass.” On Friday he threatened Iranian authorities if the number of protesters killed in crackdowns against demonstrations increased. He has also threatened to “do something” about Greenland, the Arctic island that belongs to the Kingdom of Denmark, “the easy way or the hard way.”

His argument in favor of brute force also extends domestically, as he unconditionally defends the actions of an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent who claimed self‑defense in firing at close range and killing a woman, Renée Nicole Good, whose vehicle was blocking traffic on a street in Minneapolis

While praising the use of force, Trump declares his disdain for multilateralism. As he outlined his plans to control Venezuela’s oil “indefinitely,” last week he withdrew his country from dozens of international organizations — key elements of the multilateral system that the White House argues “waste taxpayer dollars on ineffective or hostile agendas.” Most of the institutions that the U.S. has withdrawn from deal with climate change and promoting equality.

Almost simultaneously, his administration has proposed doubling the military budget to $1.5 trillion and is demanding that defense companies ramp up production to rearm. The goal is to turn the U.S. military into a colossal Godzilla that can respond to the all‑out modernization of Chinese forces and overwhelm those of other countries — “peace through strength,” as Trump likes to boast.

“My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me,” he boasted last week in an interview with The New York Times. “I don’t need international law,” he added. According to Trump, only he can decide if and in what cases a given rule can limit the United States. He believes he can use any tool at his disposal — coercion, economic sanctions, military force — to promote what he considers his country’s interests, and as he posted a few months ago: “He who saves his Country does not violate any Law.”

Divying up the world

Trump defines his vision as the “Donroe Doctrine,” a play on his name and that of James Monroe, the U.S. president who two centuries ago proclaimed “America for the Americans” to block European expansion on the continent. Some experts have described it as a division of spheres of influence among great powers, with Washington controlling what it calls the Western Hemisphere, China taking Asia, and Russia claiming the territory of the former Soviet Union.

Political scientists Stacey Goddard and Abraham Newman coined the term neoroyalism: “An international system structured by a small group of hyper-elites who use modern economic and military interdependencies to extract material and status resources for themselves,” the researchers write in an academic article.

In this hyper-elitist system, Trump enjoys an exceptional position, commanding exclusive resources such as his country’s military power and the global dollar-based financial system. He also has a wide latitude of action, thanks to presidential powers to intervene abroad that successive administrations had already expanded, especially after the 9/11 attacks.

“He is not a president who is drastically expanding his powers abroad, because he already had those powers. The question is whether he will use them judiciously,” notes Robert Strong, professor emeritus at Washington University and Lee University, in a videoconference organized by the Miller Center at the University of Virginia.

Since taking office, Trump has been testing this model of force even though he campaigned against U.S. involvement in foreign conflicts. Before the U.S. strikes on Venezuela, Trump attacked targets in Yemen, Somalia, Syria, Iran, and Nigeria. These were generally opportunistic, lightning operations. “It’s the kind of military showmanship that Trump thrives on and endorses: quick, short, with a demonstrable result, and that forces everyone else to do what he says,” notes Eric Edelman, former assistant secretary of defense for policy in the George W. Bush administration (2001-2009).

In another era, such self‑serving objectives would have been cloaked in a mantle of good intentions: rescuing a failed state, restoring democracy and human rights, or fighting terrorism. Now they are laid bare.

“We live in a world in which you can talk all you want about international niceties and everything else,” White House domestic policy adviser Stephen Miller told CNN’s Jake Tapper. “But we live in a world, in the real world […] that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power." “These are the iron laws of the world,” added the ideologue, who is close to Trump and one of the most powerful men in the administration.

Or to put it another way: “The days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over,” as proclaimed in the Trump administration’s foreign policy handbook, the National Security Strategy, which was published a month before the military operation in Venezuela.

A preview

The National Security Strategy makes it clear that U.S. intervention in Venezuela is a preview of what is to come. It’s not a one-off action; it’s the beginning. It’s not a tactic; it’s a strategy. Washington once again conceives of the American continent as its backyard, a region where the United States must have primacy, “free of hostile foreign incursions or ownership of key assets.” “This is OUR Hemisphere,” the State Department proclaimed on social media last week, in case there was any doubt.

In this vision, Europe loses relevance; it is seen as a region where multiculturalism is leading to “civilizational erasure.” Priority shifts to the American continent, perceived on the one hand as the source of what Miller and Trump consider the main security risks for the United States: immigration and drug trafficking. On the other hand, it is seen as an immense exclusive economic zone, a source of natural resources to exploit and markets to which to sell products: it is no coincidence that Trump announced last week that, according to him, Venezuela will come to buy exclusively from U.S. brands.

The National Security Strategy paints a picture in which Washington unabashedly supports friendly governments — such as Javier Milei’s Argentina or Nayib Bukele’s El Salvador — , openly endorses favored candidates — like Nasry Asfura in Honduras — , and attempts to coerce countries perceived as recalcitrant, such as Lula da Silva’s Brazil, which Washington has sought to punish with tariffs and sanctions. This coercion, as demonstrated in Venezuela, can escalate to full-blown military intervention.

For now, the intervention in Venezuela has shocked the rest of the world. Europeans are moving at breakneck speed to try to dissuade the Trump administration from possible actions in Greenland. Petro has acknowledged that before his conversation with Trump to calm tensions, he seriously feared military action in Colombia. The president of Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum, is forced to call for calm. And authorities in Venezuela are, for the moment, complying with Trump’s wishes. The new leader, Delcy Rodríguez, has offered cooperation and, according to Trump, has already promised 30 million barrels of oil to the U.S. Nicaragua is keeping a close eye on the U.S. and this Saturday released half of its political prisoners.

Trump, for his part, maintains that he enjoys broad support within the United States and that his supporters are fully behind him: “MAGA loves everything I do. MAGA is me,” he said. However, polls point to a somewhat more complex scenario: while voters are split down party lines on the military operation in Venezuela, most fear it could draw U.S. forces into excessive involvement in the South American country, potentially triggering one of those “endless wars”— like Iraq or Afghanistan — that the president had promised to avoid.

Questions about the future

This is not the only question being raised about the future. Professor Alexander Bick from the University of Virginia warns that “the seizure of assets belonging to other sovereign states sets a very bad precedent for the behavior of governments globally.”

Russia may see it as a boost to its war in Ukraine. China, as an argument for invading Taiwan. And Beijing may resist relinquishing the vast commercial and security interests it already has in Latin America: from the Peruvian port of Chancay to infrastructure investments in Colombia, including the enormous loans to Venezuela that Caracas has been repaying with oil.

“Whether the Trump model can prevail over Russia and China remains to be seen,” says Edelman.

In its annual analysis of major global risks, consulting firm Eurasia Group considers the United States the top risk in 2026.

“The risk of U.S. policy overshoot is high — especially now that Trump has a successful raid under his belt,” says Ian Bremmer, president of the risk‑analysis firm, wrote in his weekly newsletter. Trump “will be tempted to double down on what has worked so far and push further,” whether through sanctions, meddling in elections, or promoting candidates in Latin America. In the process, Trump “risks planting seeds of anti-Americanism and pushing conflict, traffickers, and cartels into new places,” which has happened “on almost every continent where America has overextended itself,” Bremmer wrote.

Although Trump boasts that he has no restraints, the first signs of resistance are beginning to appear. In the Capitol, the Senate has given the green light to advance a bill that would prohibit the president from taking new military action in Venezuela without congressional permission. The vote was supported by a group of Republicans, who joined the Democrats. Behind the scenes, Republican legislators are warning that an intervention in Greenland would shatter NATO and go too far. Abroad, the European Union last week signed a free‑trade agreement with the Mercosur countries after years of delay; the EU is working on a strategy of resistance.

And just as elections will be held this year in countries such as Brazil, Peru, and Costa Rica, where the Trump administration may be tempted to back a particular candidate, the United States will also hold elections in 2026 — the midterm elections in which control of Congress, now dominated by Republicans, is at stake.

Trump himself knows that this vote could completely upend his agenda: “If we don’t win, [the Democrats] will look for an excuse to impeach me,” he warned last week in a meeting with lawmakers from his party. The scene was a far cry from the hand-kissing ceremony seen Friday at the White House.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.