Intervention in Venezuela reignites Trump’s obsession with Greenland

The White House maintains that taking the island by force ‘is always an option’

“We need Greenland for national security,” Donald Trump declared Sunday upon his return to Washington, a day after his country’s military operation in Venezuela, during which Nicolás Maduro was captured. The immediate success of that attack seems to have fueled the U.S. president’s appetite for further interventions. The Arctic island — an autonomous territory belonging to the Kingdom of Denmark — an obsession he has harbored for years, is emerging as the next target, and members of the Republican administration are already speaking publicly about controlling it. In a statement issued Tuesday, the White House acknowledged that Trump and his team are discussing various options for acquiring Greenland and that resorting to the U.S. military to achieve that end “is always an option.”

Trump’s attraction to the autonomous territory, in a key position for Arctic control and where the United States already has a military presence — the Pituffik Space Base — is intense. His administration believes that the geostrategic importance of the giant island has skyrocketed in the last 30 or 40 years, as Arctic ice melts, new maritime routes across the northern hemisphere open up, and China and Russia become increasingly active in the region. He argues unequivocally that Copenhagen is not in a position to respond adequately to guarantee security in the area. “Denmark is not going to be able to do it,” Trump insisted in his speech on Sunday.

In parallel with Trump’s statements, other members of his administration have escalated their rhetoric to advocate for the annexation of Greenland, whether peacefully or by force. “The United States is the power of NATO. For the United States to secure the Arctic region, to protect and defend NATO and NATO interests, obviously, Greenland should be part of the United States,” declared Stephen Miller, one of the most influential figures in the administration, in an interview with CNN anchor Jake Tapper, in which he adopted a defiant tone: “We’re a superpower. And under President Trump, we are going to conduct ourselves as a superpower.”

Miller is no ordinary official. His official title is White House deputy chief of staff. But his influence extends far beyond that. He is the man who shapes the administration’s domestic policy and its ramifications overseas: he is the one behind the hardline strategy of combating immigration and mass deportations, and one of the ideologues who left his mark on the National Security Strategy published in December, which advocates for U.S. hegemony in the Americas. This Monday, Trump confirmed that Miller will be one of his four trusted advisors — along with Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, and Vice President J.D. Vance — who will coordinate the administration’s efforts in Venezuela.

Miller’s wife, Katie, who during the first months of Trump’s second term also worked as a White House advisor and is now responsible for an influential ultraconservative podcast, reopened the controversy over the future of Greenland by posting on her social networks a map of the island with the colors of the American flag and the word “Soon,” just hours after the capture of Maduro.

SOON pic.twitter.com/XU6VmZxph3

— Katie Miller (@KatieMiller) January 3, 2026

The increasingly belligerent rhetoric from the Trump administration regarding the island of 56,000 inhabitants prompted a response from the European Union on Tuesday. In Denmark, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen’s government demanded that Washington cease its threats. In December, Denmark’s intelligence services included the United States as a potential security risk for the first time. The U.S. ambassador has been summoned repeatedly to receive official protests.

In an apparent attempt to calm tensions, Jeff Landry, Trump’s newly appointed envoy to Greenland, on Tuesday backed a path toward independence for the vast territory and the signing of a series of economic agreements with the United States. Landry, appointed in December to promote the island’s integration “into the United States,” dismissed the idea that Trump intends to annex it by force in an interview with CNBC.

Rubio also struck a more conciliatory tone in a closed-door meeting with lawmakers to discuss the intervention in Venezuela. According to the Wall Street Journal, during the meeting on Monday, he emphasized that the most recent statements do not imply an imminent invasion and that Trump’s plans involve purchasing the territory from Denmark.

Trump and his administration’s interest in the Arctic island is longstanding: during his first term, he offered to buy it, an episode that ended with the cancellation of a visit by the Republican to Copenhagen after Frederiksen flatly rejected the idea. The electoral victory of Democrat Joe Biden in 2020 put an end to the discussion about what at the time seemed like mere farce.

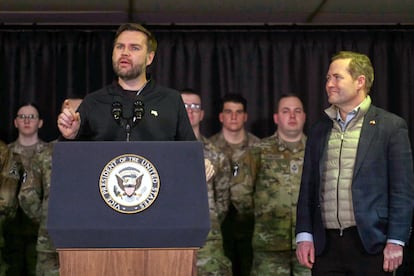

But Trump wasn’t bluffing. A year ago, on the eve of his inauguration for his second term, he revived claims to the giant island, even suggesting taking it by force. His son, Donald Jr., traveled there on a whirlwind trip, described as a mere tourist visit, but which represented a clear statement of intent. In March, Vance toured the U.S. military base on the territory with his wife, Usha Vance, where he criticized the Danish handling of security on the island: “They haven’t done a good job.”

Following Maduro’s capture, Trump and his team have emphasized the need for the United States to reaffirm its dominant position in the Americas in what they call the “Donroe Doctrine,” a play on words combining the president’s name and the Monroe Doctrine, which two centuries ago proclaimed that America should be for the Americans. In this new interpretation, Greenland is part of this sphere of influence.

“We live in a world in which you can talk all you want about international niceties and everything else, but we live in a world, in the real world… that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power,” Miller declared on CNN.

In addition to its key strategic location, Greenland has large deposits of critical minerals and rare earth elements, essential for manufacturing electronic products. Some scientists believe that parts of the island’s continental shelf could hold large deposits of gas and oil, although the autonomous government has declined to exploit them due to a lack of profitability and the environmental impact.

Despite its increasingly aggressive rhetoric, it remains unclear how the United States would attempt to carry out the annexation it so desperately desires, which Trump asserted in his address to both houses of Congress last year that they would “achieve one way or another.” A military intervention in territory under the sovereignty of a NATO member could shatter the alliance that has been key to shaping transatlantic security for the past 80 years.

Miller has indicated that this wouldn’t be necessary. While in Venezuela U.S. forces risked a local military response in Saturday’s operation, Washington anticipates that this risk wouldn’t exist in Greenland. And it has other tools at its disposal: economic and trade pressure, in the form of tariffs and sanctions, could be one of them. Or it could try to appeal directly to the Greenlandic population to support annexation or, in a solution similar to the one Washington envisions in Venezuela, a long-distance tutelage.

For the United States, the issue is fundamental. “Many members of the administration are working on this issue. It has become a key foreign policy priority for Trump. The Nordic countries are taking it seriously, slowly but surely. The rest of Europe, not so much yet,” Ian Bremmer, president of the Eurasia Group consulting firm, wrote on social media.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.