Trump softens hardline death penalty stance in cases against Mexican cartel leaders

The Justice Department’s decision, which benefits Caro Quintero and ‘El Mayo’ Zambada, marks a shift from the president’s earlier calls to execute drug traffickers

The appetizer was Genaro García Luna, the former “super cop” who was sentenced in October to 38 years in prison for organized crime. The U.S. justice system is now preparing to sink its teeth into the main course: the 29 drug lords handed over by the Mexican government to Donald Trump in the early days of his administration.

These criminal masterminds — including seasoned bosses such as Rafael Caro Quintero, Vicente Carrillo Fuentes, and Antonio Oseguera Cervantes — could provide Washington with an unprecedented map of transnational organized crime and its penetration into Mexico’s corridors of power. The cherry on top is Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, the veteran leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, who has been in the hands of the Department of Justice since being handed over a year ago in an operation worthy of a movie.

The Trump administration sent an important signal last week regarding how it is handling some of these drug lords. The Department of Justice officially notified that it will not seek the death penalty against Zambada, Caro Quintero, and Vicente Carrillo Fuentes, known as “El Viceroy.” By taking capital punishment off the table, prosecutors ease some of the pressure on the defendants and narrow the next steps to two options: work out a plea deal or face an open trial — something unlikely before 2026 or 2027.

The news came just days before The New York Times reported that the White House had instructed the Pentagon to use force against foreign cartels. The order marks an escalation from Trump’s first move in February, when he designated six Mexican organizations and two Central American gangs as terrorist groups. Several of the Mexican drug lords handed over — though not extradited — to U.S. justice were part of the structures of these criminal organizations.

The decision is no small matter given the words of Pam Bondi, Trump’s attorney general, after the 29 traffickers were sent north. “As President Trump has made clear, cartels are terrorist groups, and this Department of Justice is devoted to destroying cartels and transnational gangs,” Bondi said in February, stressing that they would be prosecuted “to the fullest extent of the law.” The court cases, however, have taken a more pragmatic turn five months into the administration.

The drug lords’ attorneys have welcomed the move. Frank Perez, Zambada’s lawyer, called it “an important step toward achieving a fair and just resolution.” Kenneth Montgomery, who represents El Viceroy in a New York court, told the Los Angeles Times that the brother of the legendary “Lord of the Skies” and leader of the Juárez Cartel is “extremely grateful” for the decision.

The decision marks a shift in the Trumpist narrative. In November 2022, when launching his presidential campaign, Trump promised that, if he returned to the White House, he would seek congressional approval for a law allowing the execution of all drug traffickers — including cartel kingpins. “Every drug dealer during his or her life, on average, will kill 500 people with the drugs they sell, not to mention the destruction of families,” he declared at Mar-a-Lago.

That promise has not materialized, despite the president’s pledge to reinstate executions. Among the flurry of executive orders the Republican signed in the first hours of his return to power was one aimed at bolstering the death penalty as a deterrent. Trump’s executive order described it as an “essential tool for deterring and punishing those who would commit the most heinous crimes and acts of lethal violence against American citizens.”

The president instructed the attorney general to seek the death penalty in all federal cases where it was warranted, especially for the murder of a police officer or law enforcement agent. This is precisely one of the most serious charges currently faced by Caro Quintero, who has been pursued for 40 years by U.S. authorities for the kidnapping, torture, and murder of Enrique “Kiki” Camarena, an undercover DEA agent who was investigating the Guadalajara Cartel.

The last prisoner executed at the federal level in the United States was Dustin John Higgs, an African American inmate sentenced for three murders who died by lethal injection in January 2021, at the tail end of Trump’s first administration. With Joe Biden’s arrival at the White House, the government shifted policy, imposing a moratorium on federal executions. The Democratic president went further, commuting the sentences of 37 of the 40 inmates on death row in the final days of his term. Upon returning to Washington, Trump ordered his attorney general to reassess these cases to determine whether the prisoners could be prosecuted again in local court systems.

The solitude of El Chapo Guzmán

The Justice Department’s decision may benefit some cartel bosses. However, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán showed last week that being one of the world’s most notorious criminals does not guarantee special treatment once behind bars.

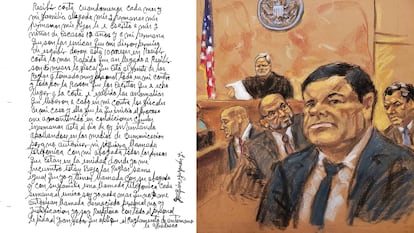

This past week, a handwritten note from the Sinaloa Cartel leader to Judge Brian Cogan — the same judge who sentenced him in July 2019 to life in prison plus 30 years — was made public. The letter was sent from the supermax prison in Florence, Colorado, where Guzmán has been held since that year. The drug lord is infamous for having escaped from prison twice.

In the letter, Guzmán Loera complains that prison authorities have prevented him from meeting with his new lawyer, José Israel Encinosa, who has spent the past 10 months trying to see his client. El Chapo also denounces that he has been unable to make phone calls or receive the nine letters his defense has attempted to send him — a right every inmate has in the United States. “For me, the lawyer is vital,” Guzmán writes, before thanking the judge for his attention.

Cogan, however, responded on Thursday that he has no say in the matter and advised the inmate to try with the Federal Bureau of Prisons. If that fails, perhaps the Colorado Supreme Court — the state where he is being held — might take an interest in his case.

El Chapo is seeking to make himself heard so that his rights are respected. Meanwhile, the U.S. government is negotiating plea deals with his two sons, Ovidio and Joaquín. The first, known as “El Ratón” (The Mouse), was the first to give in. Last month, the 35-year-old agreed to plead guilty to drug trafficking and organized crime charges. Joaquín, another leader of the Los Chapitos cell who handed over El Mayo Zambada to the authorities, is still pursuing a deal. The cartel bosses will seek reduced sentences now that lethal injection is no longer on the table.

Sign up for our weekly newsletterto get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.