El Chapo plays his last cards from prison: ‘The inefficiency of my lawyers cost me my freedom’

Since January, the notorious drug trafficker has taken on his own defense, despite not speaking or writing in English, as he navigates his new life behind bars. He has requested more visits with his wife, Emma Coronel, and demanded a retrial

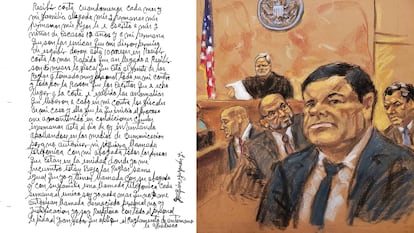

“I have been extradited to the United States for more than seven years and to this day, I have not seen the sun.” So begins one of the handwritten letters from Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, sent from the maximum-security prison in Florence, Colorado, where he is serving a life sentence following his 2019 conviction. The 67-year-old — one of the world’s most notorious criminals — has repeatedly expressed grievances about his treatment by U.S. authorities, describing the conditions of his confinement as “great torture, 24 hours a day.”

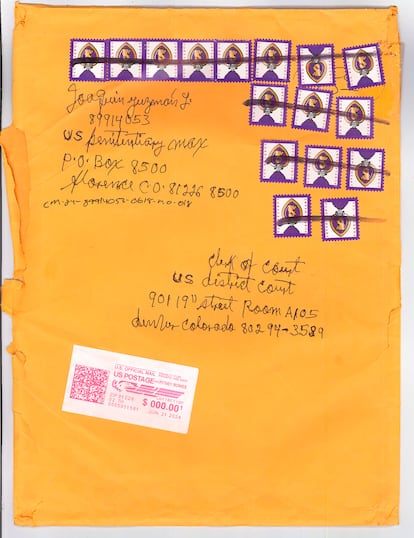

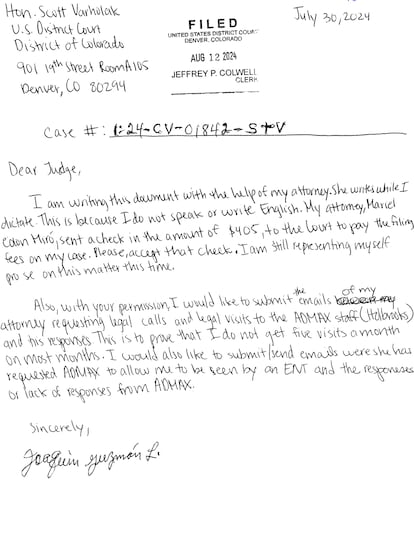

Frustrated with his requests not being met, the founder of the Sinaloa Cartel turned his back on his lawyers and, since January, has been representing himself from prison. “They had the evidence needed to confront the authorities, but they did not do it and because of that, they were very inefficient,” he says. Unable to speak or write in English, El Chapo has relied on one of his lawyers to translate and transcribe his dictated messages in a desperate attempt to improve his life behind bars and push for a retrial. “That inefficiency cost Guzmán his freedom,” says the drug trafficker, speaking in the third person, now acting as his legal representative.

From prison, El Chapo has sent out hundreds of pages of letters. Sometimes, he petitions the prison system for additional time outside his cell, increased visitation rights for his wife, Emma Coronel, and their two 13-year-old daughters, or access to materials and English classes. At other times, he meticulously scrutinizes testimony from former associates who testified against him, distancing himself from past allies and allegations while urging an appeals court to revisit his case. He has also directed letters to Judge Brian Cogan, who sentenced him to life, seeking clemency. Before taking on his own defense, he complained last year that key documents were withheld and even wrote to the then president of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, to ask for his help.

In his latest series of letters, Guzmán challenges the credibility of Vicente “Vicentillo” Zambada, son of his main partner Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada and the United States’ “number one witness.” “He [himself] said in court that the Mexican and United States governments campaigned against Guzmán to inflate his image, only to bring him down,” says Guzmán. “[There is] too much politics in my case. I ask you please to base it on Guzmán’s behavior and not on what the media says,” he pleads. “There is no justification for keeping me in these cruel and inhumane conditions,” he wrote to the director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) earlier this year.

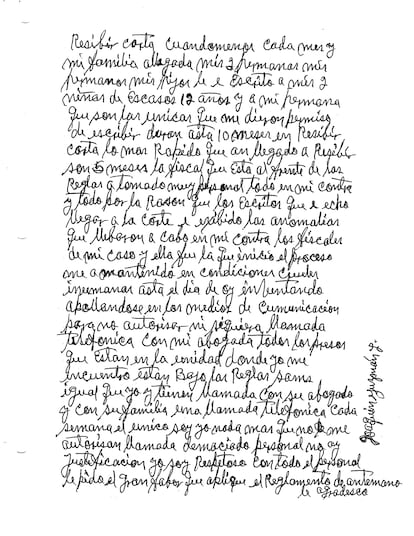

U.S. authorities, however, fear that El Chapo could escape, given his two infamous prison breaks in Mexico. The most recent, in 2015, involved a mile-long tunnel built by his associates under the maximum-security El Altiplano prison, complete with lighting, ventilation, and space for Guzmán to escape on a motorcycle. Now, Guzmán spends only three hours a week outside his cell, has no contact with other inmates or guards except during brief, handcuffed transfers, and his calls, letters, and visits are tightly controlled. Determined to avoid any risk, Washington has maintained these high restrictions. Since its opening in 1994, no one has ever escaped from Florence, also known as the Alcatraz of the Rockies.

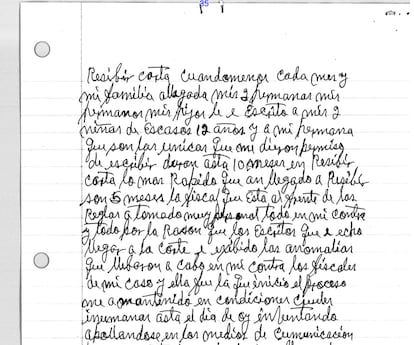

“At night, I put earplugs in my ears to be able to sleep and for my nose allergies I buy medicine here at the police station, but it doesn’t do me any good,” El Chapo said about his health. Guzmán has reported that his health issues — depression, headaches, and memory loss — have worsened and has requested treatment from a specialist. He says he is permitted monthly calls to his daughters and a sister, though he claims there have been stretches of over six months without any contact and has requested visitation rights for his wife.

“I am writing to you in the most respectful manner. I apologize for troubling you again with my previous request regarding my wife, Emma Coronel,” he wrote to Judge Cogan in April. “My wife is in California and can visit me often,” he added, emphasizing, “She is the only person in my family who could visit me.” However, the judge denied his request, stating that his court “does not have the authority” to alter the visitation restrictions. Undeterred, Guzmán has continued to send letters to everyone involved in his case.

El Chapo — who was convicted of running a continuing criminal enterprise, conspiracy to launder money, and multiple drug trafficking charges — has some access to the outside world. He can follow the news on two Spanish-language channels. “I often see President Biden [...] speaking against discrimination and racism,” he observes. “I’m sure you think like him, as a humane person. If not, the president wouldn’t have you in his Cabinet, and I ask you for a great favor to help me,” Guzmán pleads.

On July 25, the U.S. announced the capture of El Mayo and Joaquín Guzmán López, El Chapo’s son. Reports indicate that Guzmán is aware of recent events, including the ongoing conflict between his sons’ faction, Los Chapitos, and the faction of his former allies, Los Mayos.

Earlier in July, weeks before the events that reshaped Sinaloa, El Chapo submitted a 13-page document to Judge Cogan, demanding that his sentence be overturned. “The law is supposed to apply equally to all in this country, regardless of race, nationality, or even if the case is politically charged, as mine is,” he argues. He contends that his trial was rife with “inconsistencies,” alleging that prosecutors coerced witnesses to “lie” and that his defense was ineffective, labeling his attorneys as “inefficient” 65 times.

In that same document, he denies any alliance with Zambada, asserting: “It is clear there was no partnership between El Mayo and Guzmán.” He also denies initiating a conflict with the Juárez Cartel, claiming he was “unjustly blamed” for the murder of Cardinal Juan Jesús Posadas. Additionally, he dismisses testimonies from Vicentillo and nearly a dozen other figures, such as his Chicago associates Pedro and Margarito Flores and Colombian trafficker Juan Carlos “Chupeta” Ramírez, calling them “liars.”

El Chapo — the drug lord once branded “public enemy number one” in Chicago, the mastermind of immense tunnels, the feared kingpin once thought untouchable —insists his criminal reputation has been exaggerated. Yet, after a three-month trial, the jury did not accept his claims, and no authority has questioned the verdict that sealed his fate.

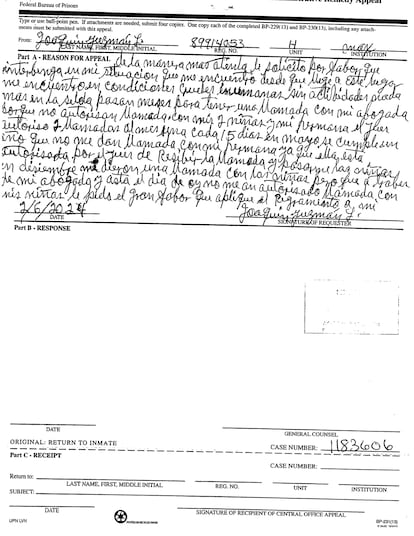

Three weeks after the capture of El Mayo and his son, in mid-August, Guzmán formally renewed his appeal in an appellate court. His first attempt was denied in 2022. The latest document he submitted was made public last week, one day before Judge Cogan sentenced Genaro García Luna, Mexico’s former secretary of public security who had collaborated with the Sinaloa Cartel for over two decades.

In his filing, Guzmán outlines several reasons for demanding a new trial: he claims his extradition was “illegal,” arguing he should have been tried in other U.S. states that had charges against him; he criticizes the “excessive” restrictions during his New York imprisonment; he alleges that critical evidence was excluded from the trial; he accuses the prosecution of misconduct; and he questions the competence of his own defense team. However, the appeals court rejected his request last Tuesday, citing errors in the filing process and late submission. “I went directly to the Supreme Court,” Guzmán explained regarding the delay, “but no one listened to me.”

One day before his latest appeal was denied, his son Ovidio Guzmán, known as “El Ratón,” made a second appearance in a Chicago courtroom. It was his first appearance since the high-profile capture of El Mayo. After the hearing, it was revealed that Ovidio and Joaquín Guzmán, sons from Guzmán’s second marriage, were considering a plea deal, which would allow them to avoid a trial.

Meanwhile, as the battle between the warring factions of the Sinaloa Cartel plunge the state into chaos, and accusations of betrayal continue to loom over the latest U.S. blow against the Mexican cartels, El Chapo — now inmate 89914-053 — is playing his last cards alone as he faces both his fate and his legacy from behind bars.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.