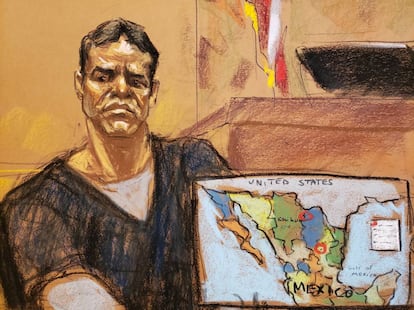

Vicentillo Zambada: a collaborator to the US, a traitor to Mexico’s drug gangs

The eldest son of the Sinaloa cartel chief has been freed from a US prison for cooperating with the authorities, but he remains the heir apparent to one of the world’s most powerful criminal groups

When Vicente Zambada Niebla was in prison, what he most liked to draw were superheroes. In the narrow confines of his cell in a federal prison in Chicago, the 46-year-old would draw pictures of Batman, Spider-Man and Superman like a child in a bedroom. It is hard to imagine whether the eldest son of one of the highest-ranking chiefs of the Sinaloa cartel, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, managed to identify more with the heroes than the villains of those movies.

Vicentillo – a nickname he has never managed to shed despite his college graduate look and carefully manicured two-day beard and in the last photo taken during his detention – was born into the bosom of the most powerful drug cartel in the world and headed some of its biggest trafficking operations. He also ordered executions from the age of 22. He was 16 years old when the first attempt on his life was made. But what his enemies say about him is that he was a traitor, and there is no greater betrayal in the drug-trafficking underworld than working with the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).

At the moment, although the US authorities have not specified his release date, Vicentillo is a free man. He is out of jail on condition that he will not travel to Mexico in the next five years and he cannot have any contact with any members of the Sinaloa cartel. Little more is known, after the authorities acknowledged the release to the television network Univisión, other than the fact that El Mayo’s son is no longer in a US federal jail. Vicentillo testified during the New York trial of drug lord Joaquín ”El Chapo” Guzmán and, as the first-born son of Zambada and a leading figure in the cartel before his arrest, he is also the main heir to one of the most powerful drug-trafficking networks in the world.

Vicentillo was arrested in March 2009 at one of his luxurious properties in El Pedregal, to the south of Mexico City. But even before then, his former lawyer told Mexican journalist Anabel Hernández for her book El traidor (or, The traitor) that he had been seeking to make a deal with the DEA. The situation in Mexico was becoming unsustainable. The war on drugs had littered the country with bodies but bloody turf wars between the Sinaloa cartel and the Arellano Félix gang, based in Tijuana, the Beltrán Leyvas (a Sinaloa splinter group) and Vicente Carrillo Fuentes’ organization had made doing business more and more difficult for a group accustomed to having the run of the house.

Vicente was willing to talk and his objective was to reveal the whereabout of his enemies. According to his own declarations in court, his testimony helped the authorities to kill or capture hundreds of Sinaloa cartel traffickers, members, associates and rivals, among them Arturo Beltrán Leyva and some members of the feared Zetas gang. Vicentillo was the DEA’s captive messenger, who served as a first-hand source for the agency and provided intelligence as to what was going on in the mountains of Sinaloa. In exchange, he was handed a 14-year sentence instead of life in prison, the standard sentence for a trafficker with his long list of crimes. That 14-year term has been gradually whittled down through good behavior and cooperation with the authorities.

The clearest example of that cooperation was his testimony against El Chapo in January 2019, when Vicentillo threw his colleague and a faithful friend of his family to the lions. Over five hours of testimony, Vicentillo was able to prove that he was familiar with Guzmán’s business and his personal retinue. He told the jury stories not only of El Chapo’s trafficking operations in Mexico, Honduras and Belize, but also about his suppliers, distributors, bodyguards, hitmen, cousins, brothers and children. He also implicated his father, who he said had a budget of up to $1 million a month for bribing officials. A Mexican Army general attached to the Secretariat of National Defense was paid $50,000 a month by the cartel, Vicentillo said. He added that his father also regularly bribed a member of the military who occasionally worked as a bodyguard for former Mexican President Vicente Fox.

“Vicente cold betray everyone, but never his father,” says Anabel Hernández in an interview with EL PAÍS. “His father was aware of his cooperation and even approved of it. It is not the first time the DEA has used such a strategy to catch drug traffickers or for their own ends. The same thing happened with Pablo Escobar years earlier. Vicentillo told his lawyer in a letter that it was El Chapo who gave him the contact to start his collaboration with the DEA in 2008.

On the day that Vicente Zambada was arrested he was just about to go to sleep. He had just messaged his wife and was under the covers when doors and windows were smashed in as the agents descended. A few hours earlier, he had been driving through the city in a top-range car with his team of bodyguards. And according to his version of events, laid out in another of his letters, he had just held a meeting with two DEA agents. “That night they arrested me, they betrayed me and I don’t know why. Th truth is I approached them of my own volition, in confidence, and I don’t know what happened,” he said in one of his letters, published in El traidor.

At that time, Vicentillo was not only the favored son of the powerful El Mayo Zambada. He was also a hugely influential figure in the Mexican drug trade and one of the three senior Sinaloa members responsible for giving orders, as he admitted to the authorities. After El Chapo’s first escape from jail in Puerto Grande (Jalisco) in 2001, El Mayo strengthened his relationship with the man who had until then been just another associate, a subordinate of the cartel chiefs of the 1990s, and together they raised up an empire on the back of violent battles with their rivals in the north of Mexico. “In 2001 I was another boss, I was the son of the cartel chief and I coordinated shipments across Central and South America. I handled corruption and manipulated people for my father everywhere in Mexico,” Vicentillo wrote his lawyer.

After his capture, Vicentillo created his own legend as a repentant drug baron. He portrayed himself as a 33-year-old man who had decided to retire from the criminal life and live in peace with his family. It was this picture Vicentillo presented during the various hearings on his case and it afforded him certain privileges in his criminal trial. Judge Rubén Castillo, who presided over the court that approved the reduction of his life sentence, acknowledged Vicentillo’s cooperation with the authorities: “If there is a so-called war on drugs, we have lost it. We have lost […] as far as I am concerned, you did not sell out El Chapo. I think it was the other way around. You cooperated with the United States of America. That is what happened. And if we didn’t have cooperators, the Department of Justice simply would not win cases. Perhaps we have lost the war on drugs, but we cannot afford ourselves the luxury of losing the war on crime,” said Castillo before handing down the ruling.

The question now is what will happen when Vicentillo is fully free again: whether he will return to the mountains of Sinaloa to take the reins of his father’s criminal empire, shaken after the jailing of his friend El Chapo, or if he will remain firm in his stated desire to live a quiet life. “The big doubt is human decision. Whether ambition does not win out, whether the thirst for power does not win out. Because his relationship of dependence with his father is very strong. If El Mayo were to say to him: ‘I need you here.’ What will he do?” wonders Hernández. In the meantime, El Mayo remains on the DEA’s most-wanted list and, unlike the majority of his associates, he has never been arrested.

English version by Rob Train.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.