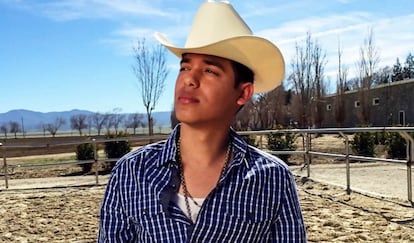

Ariel Camacho, the shooting star who inspired the modern corrido

The young Sinaloan artist died 10 years ago, but is still recognized as a major influence by the genre’s rising talents

They almost had to force Ariel Camacho to wear a cowboy hat. It was 2012 and the singer had a meeting in Los Mochis, Sinaloa, with manager and producer Jaime González, the father of today’s música norteña heartthrob Christian Nodal. “He was with two other guys, and they sang for me a corrido and a [romantic] song and that was enough for me,” González said in a Billboard interview published a few days ago. He signed the performer to his team and that humble young man, who’d shown up dressed in huaraches, a baseball cap and Levi’s jeans, would soon take Mexican regional music by storm. Camacho’s musical career ended just three years later on February 25, 2015, when he died in a car accident in the town of Angostura, Sinaloa. He was 22 years old. But his impact was far from over. Ten years later, the shooting star has become a major influence cited by today’s artists, who see in him the seed from which sprang several modern variations on the corrido.

After that meeting in Los Mochis, the manager told Camacho that artists in the sierreña genre — which is characterized by the sound of string instruments — sang in cowboy hats and boots. “But he wanted to wear those Ferragamo shoes that were in style and a little blazer. We almost had to force him to wear the tejana, and then he didn’t want to take it off,” González says in the interview. Still, that initial rupture with the norteña aesthetic that ruled the genre at the time was a foreshadowing of a generational shift that is reflected in today’s stars, who wear flat-brimmed caps and sneakers.

The legacy of Camacho (Guamúchil, Sinaloa) can best be heard in El Karma (2015), which is today a cult classic that has been honored and covered by artists like Natanael Cano, Gabito Ballesteros and Peso Pluma and even referenced by alternative musicians like Ed Maverick. Lyrics about love, heartbreak and drug trafficking mark the album’s 14 songs, which have proven key to the rise of corridos tumbados. Ariel Camacho y Los Plebes del Rancho’s Spotify profile still racks up more than six million listeners, besting the numbers of other classic regional musicians like Chalino Sánchez and Paquita la del Barrio.

A van pulls up to the Oxxo

Camacho’s first musical efforts began at a very young age. He learned to play the guitar with his father and in middle school he joined a Christian music group. That’s where he met guitarist César Sánchez, aka “El Tigre,” with whom he’d form a lasting friendship and start a band, Ariel Camacho y Los Plebes del Rancho. “He was looking for me, I remember a couple people mentioned it to me. They gave him my number, and he told me that he needed someone to play guitar and sing back-up vocals. I told him I’d do it,” Sánchez tells EL PAÍS.

After that conversation, they met up at an Oxxo convenience store. Camacho got out of a blue van and they talked. “He told me that it was a mutual friend’s birthday, and that we should play for him a little. I told him, alright, with pleasure.” It was there, in this good friend’s garage, where they gave their first concert, playing Miguel y Miguel covers. “I remember that from the first song we sang, our voices paired beautifully, they made magic. The people who were there asked us, ‘boys, how long have you been playing as a band?’ We told them it was the first time,” he says, eyes shining.

El Tigre knew Camacho was special, one of those people with whom you could immediately empathize. “He had a huge talent for people. He was always likable. He had a very cool connection.” That talent was also evident on his artistic side. Cano, an originator of corridos tumbados — a subgenre that blends the traditional corrido with urban influences — has never denied the influence Camacho had on the rise of the sound that has revolutionized Mexican music. “[Remembering his death] always makes me cry. He is the only person I’ve cried for in my life, truly. I admire him. I never met the guy,” confessed a tearful Cano in an Amazon documentary that came out in November.

Sánchez says that Camacho broke traditional barriers. “Before, you needed to have a lot of performers to form a band, in terms of Mexican regional music. He opened doors with his guitar […] I think that he laid the foundations, the roots of this tree, this new style; now, all these [corridos tumbados] guys, they’re the branches that have formed this great tree.” For Luis Omar Montoya, a music historian at Mexico’s Center for Research and Advanced Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS), the arrival of Camacho signifies a rebirth of the scene. “In comes a very young, twenty-something boy, and has without a doubt motivated many generations. That is one of the reasons why he has become an inspiration,” Montoya says.

Ariel Camacho laid the roots of this tree, this new style. All these corridos tumbados guys, they’re the branches that have formed this great tree”César Sánchez, “El Tigre”

The height of the group’s fame came between 2014 and 2015, years after corridos alterados and corridos progresivos thrust the genre into the spotlight, generating controversy with their violent content and explicit lyrics. Camacho’s subject matter certainly included romance, but he also sang stories of the drug trade, though he avoided vulgarity. “If he didn’t feel it, he didn’t record it. He always sang to love and heartbreak, and also had corridos about stories that had been in the news,” Sánchez says. González also mentions these “corridos with a message,” about overcoming, and says that the alterados and progresivos weren’t the singer’s style.

For Montoya, Camacho’s arrival at DEL Records, a major promotor of the corridos progresivos, constituted a “return to his roots,” an attempt to transition from more violent corridos into traditional corridos. “Ariel Camacho’s work is a mixture of música campirana [a string-based regional genre that includes rancheras and romantic songs] for guitars and so-called sierreño. It emerges at a moment that I see as fundamental, at a time when people are already looking for another option to the alterado movement.”

Disaster calls

At dawn on February 15, 2015, González awoke to a call from his sister, who was a crime reporter at the time. “She said, ‘brother, they’re telling me that Ariel died in an accident,’” he remembers. González told her it wasn’t true. He’d read similar, false reports in the past. He got up and went to Angostura to find out what was going on. “There, they told me that the police had already brought him to a funeral home. That’s when I realized it was true. I went to Guamúchil to deliver the news to his parents, but I couldn’t speak from the pain,” he says.

In the Alhuey cemetery outside Angostura, they built a tomb on which the silhouette of a massive guitar opens onto a kind of altar featuring a photo of Camacho. Artists visit to pay their respects to the singer. And it was there that, on February 15, 10 years after Camacho’s death, a group remembered him with the first live performance of El Plebe de Rancho, a tribute composed by Danilo Avilez. “No me fui, no me lloren/Sigo vivo en cada una de mis canciones [I’m not gone, don’t cry for me/I live on in every one of my songs].” Upon hearing the lyrics, Camacho’s mother started to sob.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.