The press under siege in the Sinaloa war: ‘Shooting at one media outlet is a warning to the others’

The battle unleashed between factions of Mexico’s organized crime groups following the arrest of ‘El Mayo’ Zambada has put journalists at the center of attacks, kidnappings and threats

The press is going through difficult times in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. The war unleashed between factions of the Sinaloa Cartel following the arrest in July of Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada in the U.S. has put journalism under siege in recent weeks. The shooting at the headquarters of the newspaper El Debate, one of the largest and most important in the state, the kidnapping of a worker from the same media outlet and the threats that have been increasing in recent times have placed the entire profession on alert. Several journalists and human rights defenders talked to EL PAÍS about the fear and uncertainty they feel as they go to work every day.

The key date was September 9. That Monday, a wave of violence without recent precedents broke out in Sinaloa. The alleged betrayal by one of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s sons, Joaquín Guzmán López, against Zambada, whom he allegedly turned over to U.S. authorities, broke a balance that had reigned for years in Culiacán. Until then, the two factions had coexisted almost without trouble in the capital city of Sinaloa. But the breaking of that “unwritten code,” says a local reporter who does not want to provide his name for security reasons, led to the war that has shaken the state since then.

The reporters were caught in the middle of this struggle, several people explained to this newspaper. “The situation is complicated by the division within the Sinaloa Cartel,” says Jesús Bustamante, president of the June 7th Association of Journalists. “We have nothing to do with it, but we have the duty to report on what is happening.” The increase in clashes between factions of organized crime led to an increase in intimidation against the profession, threats, and blockades to prevent access to the areas where the acts of violence were taking place. “All of this became more visible with the attack on El Debate,” he adds.

On October 17, just after 10:30 p.m., the headquarters of El Debate in downtown Culiacán was attacked by gunfire from a person who got out of a car with a long gun. The vehicle had been circling the media outlet for a while, and when the attacker fired at the facade, two journalists who were at the door managed to run and lie down to avoid the bullets. The bullet-riddled entrance is the one that the staff uses to enter and leave, explains a newspaper worker who declines to give his name, and at that time there are usually a lot of people around. That day, some colleagues had left just minutes before the attack. No one was hurt, but “the fear that this leaves behind does not go away.”

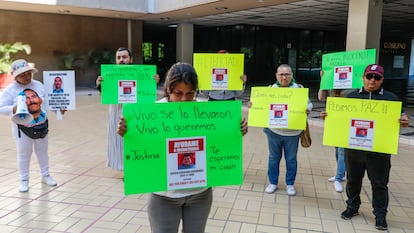

Less than two days later, the media outlet was attacked again. A deliveryman on a motorcycle who was carrying the printed editions of the newspaper was chased, attacked and kidnapped by armed criminals in the early hours of last Saturday. Since then, his colleagues and family have had no news of him. “I hope that the people who took him will take pity on him and release him,” says his colleague. The photographs distributed after the attack on the deliveryman showed the newspapers scattered next to his motorcycle, with no sign of the worker. For the other media outlets, these two attacks are a message from the criminal world to the entire profession. “By attacking a highly recognized media outlet with bullets, they put everyone on alert,” says Bustamante. “It is a warning to the others.”

When the wave of violence broke out in early September, the press began to notice signs that coverage was going to be difficult, Bustamante explains. In the previous months, if they asked permission from criminal groups to enter a red zone, they could do so. But recently, when they tried to access areas where clashes were taking place, cartel members blocked their way and warned them not to publish anything about what was happening in certain municipalities, he explains. This led journalists to stop entering rural areas, abandoning such coverage so as not to expose themselves. “We are limiting ourselves to reporting on events in the city because there is no safe way to reach those municipalities,” he says.

At least three reporters who declined to give their names said they now take extra precautions when going about their work. They don’t go out at night, they don’t go to cover a story alone, and sometimes they don’t even identify themselves as journalists. “The press is living in a context of fear,” says the El Debate worker. “We are trying to understand what the limits are so that the content you write doesn’t get you into trouble.” The newspaper’s editorial office is currently protected by the National Guard and the state police, but they don’t know how long that will last.

Jhenny Bernal Arellano, director of the Institute for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists of Sinaloa, admits that the most affected workers are crime reporters and that, in the last month and a half, complaints of attacks on reporters have almost tripled. “The climate of violence persists, we have had several incidents that are keeping us on alert,” she says in a telephone interview. The authorities have tried to downplay the situation, which continues to worsen as the weeks go by. “Any action will still not be enough to guarantee the work of the press,” she adds.

For Bernal, what the state is experiencing is “extraordinary violence” because, despite being used to dealing with adverse conditions at any given time, what is happening now is extreme. Another local reporter, who also does not want to give his name, says that “something like this has never happened before.” Several journalists remember the period of the struggle between the Sinaloa Cartel and the Beltrán Leyva group as the last major conflict they went through, beginning in 2008 and ending almost two years later. At that time, the weekly publication Ríodoce suffered an attack when two assailants threw a grenade at the editorial office.

The experiences learned at that time, however, do not diminish the fears of today. Reporters no longer fight over who has the exclusive, who gets to the scene first, or who publishes the story before anyone else. They have chosen to abandon competition and prioritize security. “The conditions are very difficult, but if we stop working we lose our essence,” says the worker from El Debate. “Journalists in Sinaloa are not just brave, they have learned to work with fear.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.