The letter from ‘El Mayo’ Zambada that widens the scandal in Mexico: A murder, a capture and a secret meeting

The Sinaloa Cartel leader has taken control of narrative over his arrest after claiming that he was going to meet with Governor Rubén Rocha and linking his detention to the murder of Héctor Cuén, an influential local politician

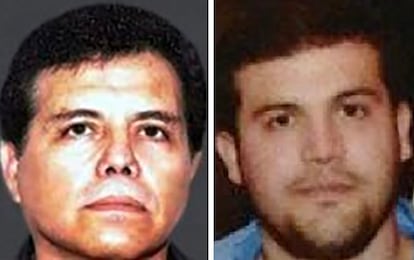

Two pages were enough for Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada to blow the official version of his capture in the United States out of the water and, in the process, shake up Sinaloa’s political chessboard. El Mayo’s letter, released by his lawyer Frank Perez on Saturday, forced Governor Rubén Rocha Moya, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and president-elect Claudia Sheinbaum to take a stand just hours after its publication. At the center of the scandal is the murder of Héctor Melesio Cuén, Rocha’s political rival, made public on the same day as the arrest of the 76-year-old drug lord and Joaquín Guzmán López, one of the sons of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. Zambada claims that he was going to meet with both men on the day of his surprise arrest, that the Sinaloa Cartel leadership was going to settle a conflict at the state’s main public university, and that one of his bodyguards was a commander in the state Judicial Police. His uncorroborated statements have sparked controversy over the influence of organized crime in Mexico’s public affairs and have provided a first warning of the scope of a potential deal between El Mayo and U.S. authorities.

El Mayo says the meeting was scheduled for 11:00 a.m. on July 25 at Huertos del Pedregal, a luxurious event hall on the outskirts of Culiacán, the state capital and stronghold of the Sinaloa Cartel. In addition to the politicians, Iván Archivaldo Guzmán, leader of Los Chapitos, the cartel faction commanded by El Chapo’s sons, was scheduled to attend. Zambada greeted Cuén, “a longtime friend of mine,” moments before meeting Guzmán López, “whom I have known since he was a child,” and who asked El Mayo to follow him. “A group of men assaulted me, threw me to the ground and put a dark-colored hood over my head,” said the drug lord of the alleged ambush.

According to El Mayo’s version, he was placed in the bed of a pick-up truck and taken to an airstrip about 20 minutes away, where he boarded the private plane in which he was delivered to the United States by his former partner. “I know that the official version given by the Sinaloa state authorities is that Héctor Cuén was shot the night of July 25 at a gas station by two men who wanted to steal his pick-up truck,” reads the capo’s statement. “That’s not what happened. They killed him at the same time and in the same place where they kidnapped me.”

Governor Rocha denied having been present. “If they said I was going to be there, they lied, and if he believed them, he fell into the trap,” Rocha said during a visit by López Obrador and Sheinbaum to the state. Rocha was careful not to give any statement at the insistence of the media, and consulted with the president before providing his version of events. The governor had said days before that he was not in Sinaloa on the day of Zambada’s arrest and Cuén’s murder. He claims he took a flight to Los Angeles around 9:00 a.m., two hours earlier in the timeline that El Mayo lays out.

Rocha took a plane belonging to private company Servicio Ejecutivos Aéreos Viz, owned by a former deputy of the ruling PRI party, Jesús Vizcarra, and his brothers, along with two of his four children, two wives and two grandchildren, according to information published by journalist Marcos Vizcarra in Espejo magazine, which had access to the flight logs. Doubts about the governor’s whereabouts had emerged because he had not given concrete details of his visit to California. On the official page of the state government of Sinaloa there was a gap in the press releases, with notes from July 24 and 26 detailing his activities, but not from July 25. “I am out of the State and from a distance I have been informed by the Secretary of Public Security of the regrettable event in which the teacher Héctor Melesio Cuén Ojeda, former rector of the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, lost his life,” said the governor in a video recorded and published on his social networks in the early morning of July 26, in which he did not clarify where he was.

The first account linking Cuén’s murder to Zambada’s arrest was published on July 29 on veteran journalist Ioan Grillo’s Crash Out Media portal. Since then, there has been speculation about the meeting with the former mayor of Culiacán, to be held in Huertos del Pedregal, and how his four bodyguards were outnumbered by Guzmán López’s hitmen. This version, attributed to a former member of El Mayo’s security team who is behind bars, expanded on the details Perez had given about his client’s capture on July 27, claiming it was a “kidnapping” at the hands of Guzmán López. It was also a possible alternative to the cryptic robbery theory put forward by the Sinaloa Prosecutor’s Office about the death of Cuén, a deputy elected by the PRI. Grillo’s text does not mention Rocha.

El Mayo’s version of events is explosive and problematic for the government because it offers a detailed account of what happened, compared to the contradictions and doubts that have surrounded the official account of the arrest. Zambada says how, when, where, and why he was arrested. His account sticks to the strategies seen in U.S. courts, where telling a good story is more important and can be more decisive than proving it. It sows doubts, beyond the evidence and statements Rocha has provided.

El Mayo’s letter did not come out of the blue. A day earlier, the U.S. Embassy in Mexico broke two weeks of silence and established the official version of its government on the drug lord’s capture. It did so with a five-point report summarizing that Zambada was taken against his will to U.S. territory. It also denied an extraterritorial operation by U.S. agencies on Mexican soil.

Contrasting versions

The White House has been extremely careful about the details shared with the López Obrador administration and public opinion, aware that its words could have a major impact on the bilateral relationship and the message sent to the Sinaloa Cartel after its leader’s capture. One of the readings from the official version — given Washington and Mexico’s insistence that the capture took them by surprise — is that the only people who knew how they had ended up in the United States were the drug traffickers involved: Zambada and Guzmán López. The table was set for El Mayo’s latest media coup. As he did after the arrest, Zambada took advantage of the gaps in the narrative that both governments were unwilling, or unable, to fill.

A cascade of revelations followed the publication of the missive. The Sinaloa Attorney General’s Office confirmed on Saturday that José Rosario Heras López, the police chief who allegedly watched El Mayo’s back, does work for the Sinaloa Investigative Police and was on vacation from July 14-30. He said, however, that he maintained that the theft of the pickup truck was the main motive for Cuén’s murder. The ministerial authorities released a video on Tuesday showing the moment when a motorcycle approached the pickup truck in which the politician was traveling, according to the testimony of his companion. The men opened the door of the vehicle, while it was stopped at a gas station, and left, according to images captured by a security camera.

The Attorney General’s Office (FGR) took over the case and said Sunday that it was already investigating Zambada’s claims, as well as the locations and people alluded to. In the same communiqué, the FGR stated that it had opened an investigation against both drug traffickers for crimes such as “treason” and “whatever comes of it,” two phrases so ambiguous that they brought a smile to López Obrador’s face during his daily press conference on Monday.

Neither the ministerial authorities nor the federal government have been able to offer a precise and different account of what happened to what El Mayo claims. López Obrador did make it clear that he had been upset by versions linking Rocha, one of his party’s state governors, to the Sinaloa Cartel leader, especially given his rivals’ insistence that the current administration is a “narco-government.” “We came [to power] with the moral high ground, we did not arrive leaving pieces of dignity along the way, we were not helped by drug traffickers or white-collar criminals,” the president stated. “We are not corrupt.”

The letter from El Mayo revives the controversy over Genaro García Luna, Felipe Calderón’s drug czar and López Obrador’s political adversary. García Luna was convicted last year in New York for collaborating with the Sinaloa Cartel over the course of two decades, following the testimonies of a dozen Mexican drug traffickers who testified against him, among them Jesús “Rey” Zambada, El Mayo’s brother. López Obrador celebrated the ruling in style and took political advantage of it. The National Action Party (PAN), the main opposition force, dug in during the weeks following the verdict. “García Luna has nothing to do with the PAN,” national leader Marko Cortés told this newspaper. The scandal surrounding Zambada has reversed the roles: Morena says that the word of a drug trafficker cannot be given credibility and has defended itself against the media blows from the United States, while the PAN has gone on the offensive.

There remains, however, a fundamental difference between the two scandals. García Luna fell after a judicial process. Rocha, Cuén and Zambada have been the protagonists of a media trial, at least until now. The possibility that El Mayo’s statements will be prosecuted is in the hands of the U.S. justice system and Washington’s political will to pursue the allegations. That is the price of Zambada being tried in the United States, predictably in New York, in the same court as El Chapo and García Luna. The capo’s letter is a sign to both governments that he knows the game well, and knows how to play it.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.