Breakthrough experiment succeeds in making a machine relate concepts as humans do

The work, published in ‘Nature,’ opens the door for generative artificial intelligence tools, such as ChatGPT, to learn faster, more efficiently and more cheaply

The human brain has a key property that makes language possible and allows us to elaborate sophisticated thoughts: compositional generalization. It is the ability to combine in a novel way elements that are already known with others that have just been learned. For example, once a child knows how to jump, they understand perfectly well what it means to jump with their hands up or with their eyes closed. In the 1980s, it was theorized that artificial neural networks — the engine on which artificial intelligence and machine learning rely — would be incapable of making such connections. A paper published in the journal Nature has shown that they can, potentially broadening the horizons for advancements in the field.

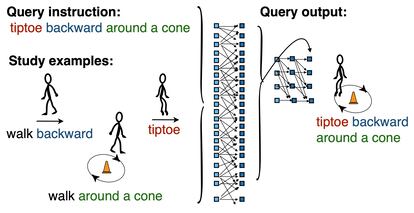

The authors of the study developed an innovative training method, which they dubbed meta-learning for compositionality. Under this method, the neural network is constantly updated and directed through a series of episodes, and in this way, it learns to relate experiences. The researchers then conducted experiments with volunteers who were put though the same tests as the machines. The results showed that the machine was able to generalize as well as or better than people.

“For 35 years, researchers in cognitive science, artificial intelligence, linguistics, and philosophy have debated whether neural networks can achieve human-like systematic generalization. We have proven for the first time that they can,” says Brenden Lake, assistant professor in NYU’s Data Science Center and Department of Psychology, who was one of the authors of the paper.

Large language models, such as ChatGPT, are capable of generating coherent, well-structured text from the instructions given to them. The problem is that, before they are able to do so, they have to be trained with a huge amount of data. In other words, huge databases are processed and artificial intelligence or machine learning algorithms are developed to enable these models to extract patterns and learn, for example, that there is a very high probability that the words “grass is colored” will be followed by “green.”

These training processes are slow and very expensive in terms of energy. Training a model like ChatGPT, which consider more than 175 billion parameters, requires a lot of computational capacity. This involves several data centers (industrial buildings full of computers) running day and night for weeks or months.

“We propose a partial solution to this problem that is based on an idea from the cognitive sciences,” explains Marco Baroni, researcher from the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA) and co-author of the study, over the phone. “Humans can learn very quickly because we have the faculty of compositional generalization. In other words, if I have never heard the phrase ‘jump twice,’ but I know what ‘jump’ is and what ‘twice’ is, I can understand it. ChatGPT can’t do that,” says Baroni. ChatGPT — OpenAI’s flagship tool — has had to learn what it is to jump once, jump twice, sing once, sing twice…

The type of training proposed by Lake and Baroni may serve as a way for large language models to learn to generalize with less training data. The next step, says Baroni, is to demonstrate that their experiment is scalable. The researchers have already proven that it works in a lab context; now it’s time to do it with a conversational model. “We don’t have access to ChatGPT, which is a proprietary product of OpenAI, but there are many smaller and very powerful models developed by academic centers. We will use some of them,” says Baroni, who is also a professor in the Department of Translation and Social Languages at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona.

Indeed, one of the authors’ goals is to “democratize artificial intelligence.” The fact that large language models require huge amounts of data and computing power limits the number of providers to a handful of companies with the necessary infrastructure: Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Meta, and so on. If Lake and Baroni’s proposal proves its worth by training such models, it would open the door for more modest operators to develop their own systems that are no match for ChatGPT or Bard.

The breakthrough presented by these two scientists may be of use in other disciplines as well. “Brenan and I come from the field of linguistic psychology. We don’t believe that machines think like humans, but we do believe that understanding how machines work can tell us something about how humans do,” says Baroni. “In fact, we showed that when our system makes a mistake, the error is not as coarse as those made by ChatGPT, but is similar to mistakes people make.”

This is evident, for example, with a mistake related to iconicity. This is a phenomenon in linguistics in languages all over the world, whereby if you say A and B — I’m leaving the house and going to eat — that means I’m going out first and then I’m going to eat. “In experimental type tasks, if you teach the human subject that, when you say A and B, the correct order is B and A, there are usually mistakes. That kind of error is also made by our system,” says Baroni.

How far can the method devised by Lake and Baroni go? Everything will depend on what happens when it is tested with large language models. “I wouldn’t know if it is a line of research that will offer great advances in the short or medium term,” says Teodoro Calonge, professor in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Valladolid (Spain), who has reviewed the code used in the experiments. He adds, in statements to the SMC España platform: “I certainly don’t think it will provide an answer to the questions that are currently being asked in the field of ‘explainability of artificial intelligence’ and, in particular, in the field of artificial intelligence.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.