Martin Scorsese, as saintly as he is sinful

A documentary series on Apple TV, directed by Rebecca Miller, brilliantly analyzes the life and work of the legendary filmmaker and uncovers secrets from his past

In the late 1970s, Martin Scorsese shared a house with musician Robbie Robertson. A house and drugs. Mountains of narcotics, confirms the lead guitarist for The Band. New York, New York (1977) had been a failure, and the filmmaker had lost his way in life. Until his body said enough, and, suffering from internal bleeding, he ended up hospitalized. “Most of me wanted to die. Because at that point, I couldn’t do my job anymore. I felt incapable of creating,” the director confesses to Rebecca Miller on camera. His friend Robert De Niro approached his bedside, pressuring him — he had been doing so for some time — to accept a project led by the actor, which the filmmaker resisted. Scorsese recalls: “He looked at me and said, ‘What the hell do you want to do? Do you want to die like this?’” No, Scorsese decided, and that’s how Raging Bull came to be made.

This is one of the anecdotes about the filmmaker that are revealed in Mr. Scorsese, a five-part documentary series directed by Miller that premieres on Apple TV on October 17, and which brilliantly analyzes the life and work of the director of Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Goodfellas, Casino, Gangs of New York, The Wolf of Wall Street and many other legendary movies.

Miller, in addition to directing feature films, had worked on another documentary about a myth, in this case her father, the playwright Arthur Miller, in 2017. She called Scorsese — whom she knows well for several reasons, including the fact that Miller’s husband is Daniel Day-Lewis, who worked with the filmmaker on The Age of Innocence and Gangs of New York — in the middle of lockdown to propose the project. So she began filming him and friends and collaborators from different eras. But given the amount of material, what was going to be a film became, after eight months of editing, a series for Apple TV, the platform that financed Scorsese’s most recent film, Killers of the Flower Moon. And even so, as Miller said during the promotion, they had to eliminate facets of Scorsese’s work such as his passion for production and restoration, or Hugo (2011), the only film he made that is not mentioned on screen.

The life of Marty Scorsese (New York, 82) cannot be understood without cinema. In reality, his life is cinema; the rest is subject to his impulses. His daughter, Domenica, remembers the best moments with her father as the days spent on the set of The Age of Innocence, in which she acted. She emphasizes: “My father is like a lighthouse: when he shines his beam on you, you’re the chosen one... And then that light turns, and you’re abandoned.”

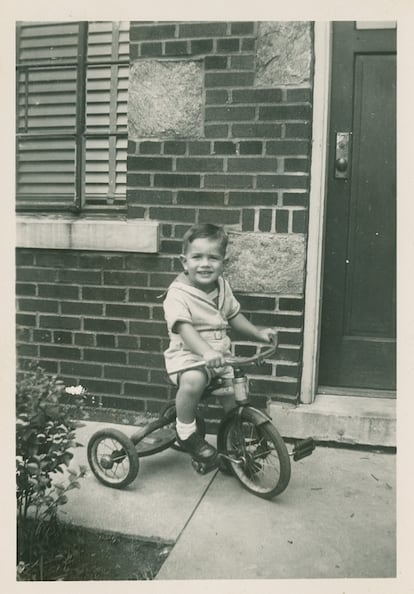

Curiously, her father almost didn’t become a filmmaker. Because his art is fueled by anger and boundless determination. Shortly after his birth, his parents left the mean streets of Little Italy to live in a small house in Corona, Queens. “Paradise,” Marty notes. Tranquility, trees, a garden. A fight between his father and the landlord, with an axe involved, sent the family back to an apartment on Elizabeth Street — that is, to violence, crime, and Catholicism. And asthma confined the boy, who viewed life for three years from a third-floor window, a vantage point that explains the frequent use of high-angle camera shots in his films. And from there, says Nicholas Pileggi, screenwriter of Goodfellas and Casino, you could see the dichotomy that has cemented his work: “In Marty’s world, St. Patrick’s Church is across the street from the Ravenite Social Club, where the mob used to meet and which dates back to the Prohibition era. Do you want to talk about the connection between those two worlds? There was this kid there watching everything that was happening. How could that not affect you?” The filmmaker himself recalls that he went to seminary (he dropped out because he liked women more), and on one occasion, chatting with Gore Vidal, he told him that in his neighborhood you could only be a gangster or a priest, to which Vidal replied: “You became both at the same time!”

Miller has free access to material and the filmmaker’s friends. On one hand, it will be a fundamental documentary in future Scorsese studies, because it analyzes and breaks down his films, both in terms of form (he draws each shot before filming), execution (he explains how he works on improvisations and gives good examples), and subject matter (why he made each film, what story he wanted to tell, and at what point in his life).

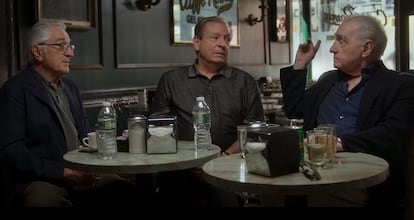

The series also unearths fascinating stories. De Niro recalls their first professional encounter and suddenly realizes that guy is Marty, whom he met as a teenager while roaming around Little Italy. Or when Miller interviews Robert Uricola, a neighbor and childhood friend, and he confesses that Johnny Boy, De Niro’s character in Mean Streets, is based on Marty’s uncle, Joe “The Bug” Scorsese, and his own brother, Salvatore Uricola, better known as Sally Gaga. Miller blurts out: “I’m so sorry we didn’t get to meet your brother.” Robert calls him, and shortly afterward, Sally appears, ravaged face, gleaming teeth, and shirt open to the navel, to recount some of his crimes from that time, as unpredictable and dangerous as his on-screen alter ego. With Scorsese, life and work are indivisible.

The director, on the other hand, misses a point. Scorsese talks about his drug-fueled hell, how meditation has helped him become aware of his anger, and how he has managed to confront and channel it. Isabella Rossellini, his third wife, recalls: “I would say Marty is a saint/sinner,” a saint because he constantly asks (and wonders) about good and evil, only to then act badly, often in real life. She adds: “He could demolish an entire room and then not remember it. At least he never hit me.”

That’s the issue that Paul Schrader, another great, describes, speaking of Taxi Driver and extrapolating it to his entire career, as a “Madonna/whore problem,” a simplification of his female characters that has never completely disappeared from Scorsese’s career. Miller prefers to talk about his actresses’ Oscar nominations rather than delve into this dichotomy, a minor detail in an otherwise outstanding portrait.

Many films tell you what to think. Marty doesn’t want to do that. He wants you to feel itThelma Schoonmaker

It is curious, because the documentary does delve into the dissonance between violence and spirituality. His editor and professional travel companion, Thelma Schoonmaker, explains: “Many films tell you what to think. Marty doesn’t want to do that. He wants you to feel it.”

In five hours, there’s time to talk about Scorsese’s numerous failures (more than people realize), which he laughingly emphasizes: “Dead again”; about how the success of the escapist films of his colleagues Lucas and Spielberg shattered his way of working in the late 1970s; about his relationship with the Oscars and how he never felt accepted by Hollywood; about the times he’s been attacked and boycotted because of his films; about how he fiercely defended his artistic judgment before producers or major studios, even with a gun in hand; about how Leonardo DiCaprio saved his cinematic vision in the 21st century; or how, in the end, he put something of himself in all his underdog protagonists (his framing lesson with Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver is remarkable in achieving that feeling).

Regarding Schrader’s script for Taxi Driver, Scorsese says that when he read it, he felt “almost as if I had written it myself.” Miller asks: “What of you, at that moment, do you feel was in Taxi Driver?” Scorsese reflects, and after a pause, replies: “The anger, the loneliness, no way of really connecting with people.” Cinema saved him.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.