Ludovic Slimak on Neanderthals: ‘It was suicide. Humans disappear when they no longer want to live because their values have collapsed’

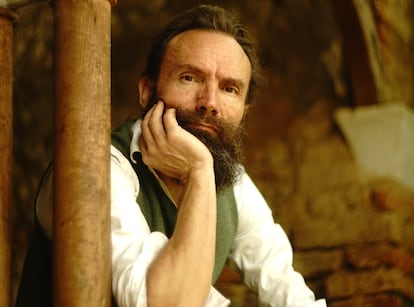

The French paleoanthropologist discusses his book ‘The Last Neanderthal,’ and provides clues about his latest discovery: ‘It’s possible that other, completely unknown human populations existed’

In his latest book, the paleoanthropologist Ludovic Slimak recounts how, as a young man, he spent his time observing people as he played the bagpipes in a kilt on the dirty streets of Marseille. Driven by an unconscious impulse, he had decided to master the instrument, and he succeeded, even leading a famous band in France. Then his first child was born, he found himself traveling from gig to gig, and eventually, he gave it up. But he was able to earn his PhD with the money he made from music.

The French scientist has been able to spend the last 30 years observing and studying one of the most decisive moments in the history of evolution: the encounter between our species and the Neanderthals, our closest human relatives. One of his latest discoveries is Thorin, a Neanderthal who lived around 42,000 years ago, very close to the moment of extinction. From then on, Homo sapiens became the only human species on the planet.

In his new book The Last Neanderthal: Understanding How Humans Die, Slimak, 52, reflects on the reasons for the disappearance of these human cousins, and what it reveals about ourselves. “It’s a sad book,” he underscores, because despite the latest evidence that Neanderthals controlled fire, created cave art, and had sex and children with our own species — leaving a trace of their DNA in our genome — this scientist from the French National Center for Scientific Research believes they went extinct in isolation and abandonment. Slimak answers EL PAÍS’ questions via videoconference from his beautiful home, where he lives with his wife and two children, halfway between Toulouse and the Pyrenees.

Question. What story do Thorin’s remains tell?

Answer. The moment of Neanderthal extinction is invisible, impossible to grasp; we have no data. What we learned about Thorin, after almost 10 years of research, is that he belonged to a distinct group from the classic Neanderthals of Europe, and that when he died he was isolated. But not geographically, nor physically.

Q. In what sense then?

A. Mandrin Cave is in the Rhône Valley, a vast migration corridor between the Mediterranean and mainland Europe. It’s a place of contact and exchange, but Thorin’s DNA tells us that his group had been isolated for some 60,000 years. And yet, there were other Neanderthals just a two-week walk from this place. How is that possible? I think it’s because they rejected contact.

Q. Is it possible to spend so much time in isolation?

A. They were happy in their small valleys. They didn’t want to explore the world or spread their genes. That’s radically different from us, who are explorers by definition. We’ve been to Greenland, to the Moon, and now we want to go to Mars. This goes beyond genetics; it’s a deeper and more interesting question: Is it possible that for Neanderthals, their relationship with the world was to have a small territory and stay there forever?

Q. What does that say about their minds? Were they more or less intelligent?

A. The problem is that we define intelligence in comparison to our own. But there are animals that are super-intelligent. In African valleys, there are very different chimpanzee cultures that live separated by a river. It’s very difficult to imagine these kinds of divergent minds, but we are surrounded by them. We have to accept that Homo sapiens is not the definition of human, nor of intelligence. The real question is how that other mind worked.

Q. Is it possible to find out?

A. It’s not just a matter of culture, but of ethology, of behavior. If I raised a Neanderthal baby like my own child, there wouldn’t be a problem with the bond. The question is whether, as they grew up, they would understand the world the same way my other children do. They would probably absorb my culture and traditions, but not necessarily. There would be something inside them that would condition them to see the world in their own way; limitations that not even the culture I taught them could overcome.

Q. In your book you conclude that they disappeared due to the collapse of their “mental sphere.” What do you mean by that?

A. In the book, I tell the story of Ishi, a Yahi Native American who lived in what is now California. Ishi suddenly appeared in Oroville in 1911. No one expected that there were still Native Americans, naked with their bows and arrows, in that area. What happened was that Ishi’s group consciously became shadows, they hid from the white people, and acted as if they didn’t exist. They lived like that for a century and a half, without any contact with Westerners. Their territory kept getting smaller.

They were hunter-gatherers; they needed to hunt unseen. And in the end, it became unsustainable. Ishi was the last of his lineage, and of his own volition, he decided to go and die where the Westerners were. He considered them demons and wanted them to kill him. Anthropologists were called from all over the country, but they couldn’t communicate with him. In fact, they never even learned his name. Ishi means human; he was simply saying that he was a human. There are many other examples. When these groups can hide, they do. And if anyone finds them, they kill them.

For several years, I worked in Ethiopia and Djibouti. There are still tribes of hunters and nomadic warriors living there. Contact with different cultures, such as Western culture, causes all their values, their way of understanding the world, the stories they tell their children, and their mythologies to collapse. After contact, these stories look odd. The children stop recognizing themselves in their parents, in their elders; they no longer want to go on. Many fall into drugs or alcohol. In the capital of Djibouti, a large part of the population lives under the influence of drugs. The young people only dream of emigrating to Yemen, where the worst kind of slavery imaginable awaits them.

Q. And did something like that happen with the Neanderthals?

A. Homo sapiens tools are standardized. Neanderthals, on the other hand, had a much more unique and creative, though far less efficient, way of using them. It’s clear to me that these humans collapsed. Depending on the region, they may have chosen to become invisible, and in others, they simply no longer wanted to go on living. It was an individual and social suicide of the population. This is how humans disappear: when they no longer want to live because their values have collapsed.

Q. Does that say anything good about us, the group that prevailed?

A. This suicide, this collapse, isn’t because sapiens is evil. The problem is that we are driven to be efficient. It’s genetic. We need to all do the same thing at the same time. It’s terrifying. When you understand this, you see the history of the 20th century. How we were capable of genocide. The Germans did it, but it could have been any other country in Europe. How can we describe our tendency to reject difference? If we don’t succeed, it will happen again. In Poland, during the Holocaust, the Nazis suggested to a police battalion that they kill Jewish children with a bullet to the head. They weren’t obligated; if they didn’t want to do it, that was fine. But despite this, the vast majority carried out the executions. It’s our tendency toward synchronization, standardization, group integration, conformity, and the fear of being marginalized.

Q. Humans also cured cancer, reached the Moon, and have tamed the atom…

A. Yes, we do good things. That ability I’m talking about is one of the keys to our historical success. But the mechanisms that enable cooperation and institutional stability also make humans highly susceptible to collective alienation when the norm shifts toward violence or ecological destruction. My intention is not to denigrate sapiens, but rather that by putting words to our fragilities, to our dangers, we can begin to change them. My work has gone from excavating Neanderthal caves to trying to understand what we are and how to act to be better humans. Despite our science and knowledge, we remain blind. Being better requires cultivating a genuine desire to understand and love those who are different. Without recognizing our intrinsic behavior, there will be no change.

Q. Is it possible that Neanderthals didn’t disappear on their own, but rather by living among Homo sapiens, perhaps even with a partner of that species?

A. In this field, it’s easy to say almost anything because the dating ranges are so broad. In Thorin’s case, for example, the fossil is between 40,000 and 45,000 years old, give or take a thousand years. But in Mandrin Cave, we analyzed the soot and saw that at most six months passed between the last Neanderthal fire and the first Homo sapiens fire. That means they were in the same place, together, but not mixed up. When Homo sapiens are present, we only find Homo sapiens tools; and the same is true for Neanderthals. Never together. I can’t help but think this is a sad story.

Q. Are we still incapable of seeing the other?

A. Absolutely. Look at Greenland. The media debate focuses on geopolitics, resources, and the economy, ignoring the fact that it’s not an empty space: it’s home to Inuit populations with millennia of history. This blindness isn’t new. Back in 1955, the United States built Thule Station, the largest in the world outside its territory, in total secrecy, without consulting the inhabitants who lived there. Now, in 2026, we continue to deny that Greenland belongs to the Inuit.

Q. Do you have any new discoveries?

A. Yes. I can’t give out any details because we’re going to publish it in a scientific journal, maybe in two or three years. And I’ll write my next book about this, which will be called something like The People of the Forest. We are working on layers dating back over 100,000 years, corresponding to an Europe covered by vast primary forests. It is a fascinating and still largely unknown phase. We know very little about how human populations lived in those dense, closed landscapes. Our image of Neanderthals is too heavily shaped by the cold and the glaciations, but before the ice, there was forest. These could be populations that developed very specific lifestyles in those environments. We are only just beginning to understand it. We have years of work ahead of us.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.