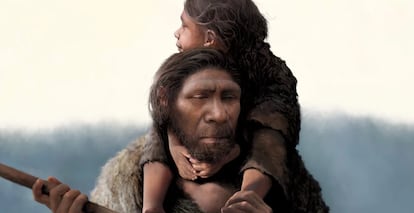

The first Neanderthal with Down syndrome shines light on the origin of human compassion

The discovery in Spain of the fossil of a six-year-old child with serious ear injuries suggests that their family took care of them without expecting anything in return

The analysis of a fossil the size of a thumb found in the Spanish city of Valencia in the 1980s has made it possible to identify the first case of Down syndrome among Neanderthals, our evolutionary first cousins, who disappeared about 40,000 years ago for unknown reasons. The remains were that of a six-year-old boy. According to the scientists who identified and analyzed the remains, this finding demonstrates that the Neanderthals also took care of the weakest members of their community without expecting anything in return, an altruism that was thought to be exclusive to our species, Homo sapiens.

One of the features that differentiate Homo sapiens from Neanderthals is the petrosal, a dense cranial bone located behind the ears. Subtle differences in the architecture of this bone are related to changes in the auditory system. When the petrosal bone of a child individual was found years ago in Cova Negra, a Neanderthal site near the Spanish town of Xàtiva, it was thought that to belong to another of the Neanderthal children that had already been located in this cave.

The remains were analyzed by Ignacio Martínez and Mercedes Conde-Valverde, experts in the auditory differences of sapiens and Neanderthals, who used computerized axial tomography to analyze the fossil. The surprise was immediate: the bone had marks of congenital malformations that are normally associated with Down syndrome.

It’s not known if the child from Cova Negra was a boy or girl, but researchers do know that the injuries to their inner ear probably left them deaf and with hardly any balance. According to the researchers, who published their findings in Science Advances, it is impossible for the child to have survived without the care not only of their mother, but also other members of their family.

It has been debated for decades whether any other human species is capable of the kind of altruism that’s seen in caring for the weak or sick without expecting anything in return. There are hardly any known cases. But in 2016 researchers published the case of a chimpanzee born with Down syndrome. The offspring survived almost two years thanks to the care of its mother and older sister. When the latter died, the mother could not take care of her sick daughter and she passed away.

In our own species, the oldest cases of Down syndrome date back some 5,000 years, according to a study published in February based on DNA analysis. None of the children identified survived more than 16 months, although several of the children found in the Iberian Peninsula were buried with honors.

The Cova Negra child is the first case of Down syndrome among Neanderthals. Although the bone has not been dated yet, the site where it was found dates back between 270,000 and 146,000 years ago. These were Neanderthals, the native human species of Europe, who lived in small clans and led a nomadic life in search of game. Despite the harshness of this existence, the Cova Negra child survived to the age of six. A gap of time later, in 1929, the life expectancy of children with this condition was only nine years, the authors of the study point out. Today, thanks to medical advances, as well as better social protections for this community, people with Down syndrome have a life expectancy of around 60 years in developed countries, the researchers add.

“This discovery is a bombshell,” says Juan Luis Arsuaga, co-director of the Atapuerca archaeological site and co-author of the study. “It shows that trisomy [the cause of Down syndrome, characterized by three copies of chromosome 21] existed at any time. But above all, it invites us to think about this child, who was cared for by an entire family and who survived for years. It is clear that this type of altruism is not exclusive to our species,” he says. “Neanderthals greatly appreciated their children, and we know this precisely because many children’s remains have been found in Cova Negra that we think received burials.”

Archaeologist and midwife Patxuka de Miguel, one of the authors of the study on the first cases of Down syndrome among sapiens, describes the new research as “excellent.” “I don’t know if the group that lived in Cova Negra was aware of the importance of each person who was born in the group, but I believe that in all societies in which survival is based on this collaboration, no one was superfluous. In the case of the Neanderthal population, it is increasingly assumed that they had knowledge about the use of resources for some pathologies, a symbolic world of their own and took care of people with sequelae of serious pathologies who survived for a long time after their suffering,” she says.

Edgard Camarós, archaeologist at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, believes that this is an “exceptional” find. “It opens a whole window to the archeology of caregiving; something very interesting to understand our evolution. It is true that this is a single case, and the diagnosis is based solely on a scan. I understand that it would also require genetic studies, especially to find that mutation on chromosome 21, which is what would confirm Down syndrome,” he details.

Miguel Botella, a doctor and paleopathologist from the University of Granada in Spain, highlights: “Although the complexity of their behaviors was already known, this is a new approach of interest because it is a child. However, the ascription of the ear pathology to a possible Down syndrome should be treated with extreme caution, as it is by no means exclusive to Down syndrome,” he adds.

Chris Stringer, paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, points out: “Although the severity [of this condition] may vary greatly in affected individuals today, the degree of pathological alteration suggests that this child was severely disabled and would have required considerable social support from others until the time of his death,” he explains. This study “adds another element to our view of the humanity of Neanderthals, capable of deep and lasting care for their own,” he concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.