Memes are a key tool for extremist communities and conspiracy theories

A study identifies the language of the internet based on text and images as a formula for representing the world view of groups that subscribe to hoaxes

Memes are not just a simple game of images and text, with more or less irony or grace. According to the Institute for Digital Safety and Behaviour (IDSB) of the University of Bath in the UK, they are the main “internet language for communicating narratives in simple, shareable formats,” “cultural representations” that unite and involve groups. But this popular communication tool is not harmless. According to a study by the British institution, published in Social Media and Society, for the most extremist communities and subscribers to conspiracy theories, they are essential for sharing and spreading “their vision of the world,” strengthening ties and transmitting deceptions: wolves in sheep’s clothing in online communication.

For Limor Shifman, professor of communication and journalism at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and author of Memes in Digital Culture (MIT Press), these creations are “units of culture that spread from person to person and reflect general social mindsets in an accessible and emotionally resonant way.” This quick-to-digest message characteristic is especially relevant, according to IDSB research, in communities where conspiracy theories are rife, “where users feel they are interacting with others like themselves, as like-minded alternative thinkers.”

“These communities attribute social events to hidden plots and the manipulative power of a shadowy elite. In revealing ‘what is really going on,’ members position themselves as an enlightened minority, in stark contrast to the uninformed majority epitomized by the general population,” the researchers explain.

And it is in this context that memes are most effective: “Given their ability to distill and communicate narratives, internet memes likely play a significant role, reflecting and thus reinforcing the collective understandings — or “conspiracist worldview” — of community members.”

Emily Godwin, lead author of the paper, details this conclusion: “Memes play an important role in reinforcing the culture of online conspiracy theorist communities. Members gravitate toward memes that validate their conspiratorial worldview and become an important part of their narrative. Their simple, shareable format allows for the rapid spread of harmful beliefs.”

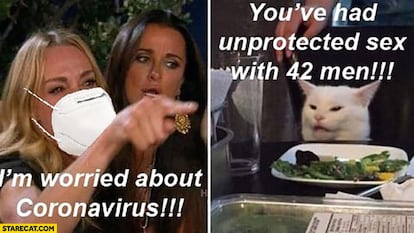

Contrary to what one might imagine, their ability to transmit does not depend on their originality, but quite the opposite. In fact, during the research, the 20 most-used memes were identified, among which NPC or Wojak (a basic representation of a person with almost no features), Soyjaks versus Chads (two men facing each other), Lisa Simpson on the blackboard, a woman yelling at a cat, or the well-known man who turns around to look at a woman while walking arm-in-arm with another, stand out. The roles attributed to the characters and cultural representations are also repeated, which are summarized in a deceitful, selfish, and shadowy elite that manipulates the rest of society, a deluded and uninformed majority, and the superiority of the group as an “enlightened minority committed to free thought and independent research.”

These representations not only multiply the message, but have the added effect of a cohesive element. As Godwin explains: “General themes create a general framework of understanding that guides members through conversations about collective concerns. Because of this, they act as a balm for disagreements that arise, reducing the possibility of fracture over minor differences. This cohesion allows dangerous ideologies to take root and flourish.”

Another purpose of these messages is to attract new members, explains Brit Davidson, associate professor of analytics at IDSB and co-author of the study: “The humor in memes is likely a key factor in attracting new members to these groups, including people who may not be aware of the full context and impact of the misinformation.”

The people most vulnerable to misinformation disguised as memes are the gullible, who are less able to recognize falsehoods, and the distrustful, who are “more susceptible to conspiratorial thinking,” according to a study published in PLOS Global Public Health by Michal Tanzer and a team from University College London.

According to Tanzer, the basic principle is a concept she calls “epistemic trust,” which is the predisposition to consider what others communicate as meaningful and generalizable to other contexts. This model of trust bypasses the necessary verification and updating processes. Chloe Campbell, co-author of the study and from the same institution, warns that these conditions affect not only people’s capacity for psychological resilience, but also their social functioning.

This blind trust in what is communicated is also evident in a study published in Nature Human Behavior by a team from Pennsylvania State University, which analyzed more than 35 million posts over three years on Facebook, although the patterns found are repeated on other social networks. The researchers found that around 75% of the content is shared without the re-sender even consulting the included link. Extreme political content, both right-wing and left-wing, is redistributed in this way more than neutral topics.

“It was a surprising and scary finding that more than 75% of the time, Facebook posts are shared without the user clicking through first,” said S. Shyam Sundar, the paper’s lead author and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. “I had assumed that if someone shared something, read it, and thought about it, they were supporting or even defending the content. You might expect that maybe some people would occasionally share content without thinking it through, but why are most reshares like this?”

Sundar himself offers an explanation: “The reason this happens may be because people are simply bombarded with information and do not stop to think about it. In such an environment, misinformation has a greater chance of going viral.”

“The study explores the sociocognitive processes associated with two of the most pressing global public health issues in the contemporary digital age: the alarming spread of fake news and the breakdown of collective trust in information sources. Our research seeks to explore the possible psychological mechanisms at work shaping individuals’ responses to public information,” the authors note.

The investigation included data from the fact-checking service Meta has suppressed in the United States following Donald Trump’s return to the presidency. It identified 2,969 links to false content that were shared more than 41 million times, without being clicked on.

There is a wealth of work on the forms and impacts of digital communication, and while the University of Bath researchers have focused on memes and the Pennsylvania researchers on Facebook, the British team admits that the field of digital expression is very broad and is considering adding to their work research on the role played by emojis, hashtags, online rituals and community-specific jargon — the ingredients on the chopping board of disinformation.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.