Sex, war and cannibalism: The impossible hunt for the Neanderthal mind

Paleoanthropologist Ludovic Slimak questions the current vision of our closest related species

In 2017, a telescope in Hawaii discovered a 1,300-foot-long missile-shaped object traveling at full-speed through space. It was coming from a star beyond the Sun. Speculation about a possible alien visit skyrocketed. This reaction reveals one of the greatest shortcomings of human beings today: we feel alone in the universe. And, as a result, we long to find another equivalent form of intelligence to communicate with and compare ourselves to.

The last time such an encounter occurred was on our own planet, tens of thousands of years ago, when members of our species from Africa came face to face with Neanderthals, humans who had lived and evolved alone for hundreds of thousands of years in Europe. And, despite more than a century-and-a-half of scientific research, we still have no idea what kind of intelligence they had, nor exactly what kind of humans they were.

French paleoanthropologist Ludovic Slimak defines himself as a “Neanderthal hunter.” He boasts of spending 30 years slipping into the “cracks and crevices” where those humans lived, ate and slept before they became extinct forever, some 40,000 years ago. His desire to understand them has taken him from the scorching Horn of Africa to the icy latitudes of the Arctic Circle, as he searches for new fossil remains. He recounts this vital journey in his book The Naked Neanderthal: A New Understanding of the Human Creature (2024).

Slimak writes that one of the places where new answers may be found is in the tundra of the Russian Arctic. Tens of thousands of years ago, while an uninhabitable Europe was covered in mile-thick glaciers, the climate of the boreal regions of Eurasia and America was unusually favorable. These areas were populated by numerous animals, who made for ideal game. In the north of Russia, mysterious remains have been found that could demonstrate that Neanderthals were the first species of human to live in the great north and that they had superior intelligence. For instance, the deep marks on mammoth tusks, or the traces of hunting and defleshing show that human activity was occurring 48,000 years before any Sapiens had arrived in the area.

In the Russian Arctic, Slimak — who works at the French National Center for Scientific Research — has found Mousterian stone tools (typically of Neanderthal origin) from 28,500 years ago. This finding, published in Science back in 2011, posits the existence of a group of Neanderthals who continued to live peacefully in Siberia 12,000 years after their supposed extinction. While waiting to find more remains, Slimak admits that this is one of the many mysteries surrounding the species.

Another key place to delve into the Neanderthal mind is the Néron Cave in southwestern France. This is where Neanderthal bones were found — bones that had been chewed by members of this same species. Cannibalism is a very human behavior, so much so that a cultural complexity exclusive to our species has been attributed to it. You can devour the enemy to make his power disappear and transform him into feces, or eat the remains of a beloved family member with great respect.

The notion of cannibalism without hunger or necessity is deeply cultural. However, in the 19th century, when the remains of Neanderthal cannibalism were found in the Néron Cave, it was concluded that the cannibalism that took place was, in fact, an act of desperation due to hunger. One scientist summarized that Neanderthals weren’t civilized enough to be anthropophagous.

In a nearby site, Slimak found the remains of six Neanderthals — including two children — who were eaten. The marks on the bones show that they were defleshed with much more care than the animals who were consumed due to simple hunger. In addition, there were marks on minimally nutritious parts, such as the phalanges of the fingers.

Back in 1854, the Scottish doctor and explorer John Rae reported that the Inuit people of the Arctic had told him of their encounters with a group of starving and sinister humans who had devoured several of their companions. They were, apparently, the last survivors of the Terror and the Erebus, two British ships that had set sail in 1845 with the intention of opening the Northwest Passage, but had been lost in the ice. In 2015, analysis of some of the crew members’ skeletons showed marks not only stemming from dismemberment and being cooked in pots, but also from intentional bone-breaking to access the marrow. This story helps Slimak argue that cannibalism due to hunger only occurs among desperate humans who have strayed beyond their territory. The Inuit, for example, haven’t engaged in cannibalism, despite living in a very harsh environment. The Neanderthals at the French site — who lived about 100,000 years ago — were highly adapted to their environment and it’s unlikely that climate change transformed their surroundings so much as to render them lost and desperate.

So, were the Neantherthals cultural cannibals? According to Slimak, it’s impossible to know for sure. One of the most human behaviors is to attribute meaning to objects — the so-called “symbolic thinking” that was believed to be exclusive to Sapiens. However, in recent years, this behavior has also been attributed to our Neanderthal cousins. But Slimak dismisses this possibility, referring to the fact that the shells or claw necklaces supposedly made by Neanderthals may just be superficial. He thinks the same about feather ornaments, referring to “the Neanderthal Mohican.” He also doesn’t accept Neanderthal rock art as being legitimate, because, he says, the carbon dating isn’t consistent.

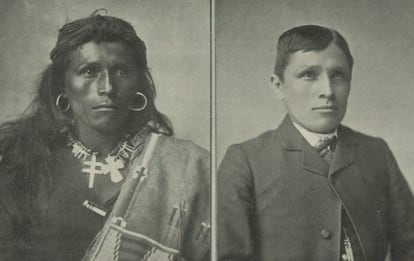

Slimak attacks the so-called “scarecrow Neanderthal,” whom we have disguised as ourselves. It’s often said that we wouldn’t be able to identify a member of this species if he were clean-shaven and well-dressed. The origin of this oft-repeated phrase lies in a 1939 image, in which anthropologist Carleton S. Coon portrayed a Neanderthal wearing a hat. The headdress hid one of the most Neanderthal-like physical features: the pronounced arch of the eyebrows, unmistakably characteristic of this species. The French archaeologist compares this attempt to rehabilitate a Neanderthal into looking like us with the case of Tom Torlino, a member of the Navajo Nation who was forcibly integrated into American society in 1882. His hair was shaved off by force, while his earrings and pendants were removed and stolen, before he was dressed in a suit.

“Having disappeared from the earth, the Neanderthal has been transformed — and is still being transformed — by us into a lifeless doll. Victor Frankenstein was only an experimenter, a precursor. We are the macabre inventors, the puppet masters of these marionettes from times gone by,” Slimak writes in The Naked Neanderthal.

The last stop in the Neanderthal hunt is the Mandrin Cave, in southeastern France. Here, Slimak has made his most controversial discoveries: the traces of the presence of Neanderthals and Sapiens overlapping in the same period of time. Slimak’s theory is that the extinction of the Neanderthals couldn’t have been unrelated to the arrival of the Sapiens. In his opinion, one of the key tests that differentiates one species from the other is in their respective ways of killing.

Judging by paleoanthropological remains, Neanderthals made very few weapons. 99% of the stone tools they carved were used to cut meat or tan skins. It’s thought that they hunted and killed at very close range, skewering their prey with wooden spears (which haven’t been fossilized). This left many of them with war wounds that have subsequently been identified in their remains. On the other hand, Sapiens manufactured stone weapons in almost industrial quantities. Many of them, such as arrowheads, were intended to hunt at a distance.

In the Mandrin Cave, there are arrowheads (supposedly belonging to Sapiens) that show marks of having hit bones. These are estimated to be around 54,000-years-old. Yet, it’s thought that our species arrived in Europe about 40,000 years ago. Hence, for now, this site is a mysterious exception.

Much earlier, about 100,000 years ago, and also later, about 55,000 years ago, Sapiens and Neanderthals met in Asia and the Middle East. They then procreated. Contemporary genetic analyses indicate that only the Sapiens accepted the children who were born from these encounters between tribes, since the last Neanderthals no longer had the Sapiens’ genetic markings. Meanwhile, our species continues to have Neanderthal DNA, which has given us a better immune system, as well as a greater risk of suffering from depression, among other things.

Given all this evidence, Slimak believes that there was not just one, but rather several waves of Sapiens that arrived in Europe, encountered the Neanderthals and ultimately lost the battle for territory. That is, until the last wave triumphed, which implied the extinction of the last human intelligence (other than ours) that remained on Earth.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.