From glory to derision: 25 years of the concept album that ended The Smashing Pumpkins’ fame

Billy Corgan’s band produced classics in the 1990s, but the dawn of the 21st century turned them into an experimental and confusing group even for their own fans, although others point to their vision when it comes to understanding rock and the influence of the internet in today’s world

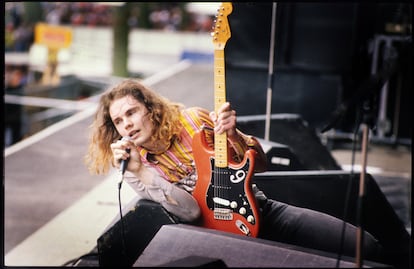

The Smashing Pumpkins were one of the most successful bands of the 1990s, but the turn of the millennium didn’t sit well with them. They decided to release one last ambitious album and disband at the end of 2000. At the time, frontman Billy Corgan was 33 years old, and the Pumpkins had sold 25 million records. Their music wasn’t exactly commercial, but those were different times: not only did they benefit from the alternative rock boom of that decade, they also knew how to broaden their fan base by unprejudicedly introducing influences closer to heavy metal, progressive, and gothic-inflected pop.

Although it wasn’t officially announced until May 2000, the idea of ending the group was put forward by its four original members (vocalist Corgan, guitarist James Iha, bassist D’Arcy Wretzky and drummer Jimmy Chamberlin) at the end of 1998. They had just released their fourth album, Adore, with influences closer to industrial electronics and dark pop, and, although they defended it tooth and nail, their popular adoration began to decline after having peaked with the double album Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness (1995).

Their record label, Virgin, was beginning to show dissatisfaction with the situation, and their manager, Sharon Osbourne — yes, Ozzy’s wife — decided to no longer work with them. In reality, there was an elephant in the room: the fallout between the band members. Chamberlin had already been expelled in 1996 after the overdose death of keyboardist Jonathan Melvoin, who was with Chamberlin at the time. Chamberlin had also taken the same amount of heroin, but managed to survive and, after undergoing rehabilitation, was reinstated in the group. However, the next to be dismissed by Corgan was Wretzky, also (according to his version) due to her addictions. Machina/The Machines of God (2000) was the last album recorded by the original Smashing Pumpkins lineup. For what was to be the final tour, called The Sacred And Profane Tour, Wretzky’s replacement was the charismatic Melissa Auf der Maur, who was then playing with Courtney Love in Hole.

A pretentious rock opera

Machina, released in February 2000, was intended to be celebrated as a return by Smashing Pumpkins to their more hard rock roots, although in reality it was an eclectic work that erratically pointed in very different directions. Corgan’s initial idea was to deliver a rock opera, a very long and theatrical concept album.

“The band had become such cartoon characters at that point in the way we were portrayed in the media, the idea was that we would sort of go out and pretend we were the cartoon characters,” he told New Times magazine in 2010. From there he conceived a story that revolved around a rock star named Zero (who would be Corgan’s alter ego as potrayed by the media), who hears the voice of God, renames himself Glass, and rechristens his band The Machines of God. In turn, his band’s fans were known as “The Ghost Children.”

But the concept remained half-finished. Part of it was communicated in various promotional campaigns tied to the album’s release, and in texts written by Corgan on his website and in the CD’s inner booklet, which he accompanied with illustrations by the Russian painter Vasily Kafanov and which linked the story with references to alchemy, metallurgy, physics, medicine, astrology, semiotics, spirituality, and more.

Furthermore, the band’s leader started an online puzzle game with fans, The Machina Mystery, and posted his favorite interpretations. This whole process continued in 2001, with a viral campaign on the band’s website inviting fans to search for mysterious sites and music videos. This was followed by the idea of an animated series that was also never completed. In his 2010 interview, the musician admitted that he was never sure “what the fuck I was trying to do.” “I kind of don’t understand why I made some of those choices, ‘cause they seem kind of silly to me now. But at the time, they made total sense to me.”

The public didn’t understand either, and the album was the lowest-selling of their career up to that point. A change of era had occurred, one now beginning to be dominated by the nu-metal of Korn and Limp Bizkit, although the fundamental factor was that the Pumpkins simply hadn’t given their fans what they had expected. “Adore hadn’t alienated the public. Machina had,” Corgan would later acknowledge.

But Corgan wasn’t finished there. The frontman’s idea was to release two double albums. Virgin, sensing the impending disaster, refused from the start, so Corgan decided to make the sequel (titled Machina II/ The Friends & Enemies of Modern Music) available online for free in September 2000. He also decided to self-release a run of 25 numbered vinyl copies (actually, a box set with two LPs and three 10-inch EPs), which were distributed among friends of the band.

The album was accompanied by instructions for ripping the content online, so that all fans who wanted it could easily access it. Currently, the album is still not available on any legal streaming platform, but it’s very easy to find on YouTube. With this move, the Chicago band unwittingly anticipated what Radiohead and many others would do years later. Piracy was still a problem in its infancy, but the massive collapse of the record industry was nowhere in sight at the time.

Fan alienation also extended to the final tour, which was as extensive as it was disappointing. It arrived in Spain in October 2000, with five stops: Santiago de Compostela, Madrid, Barcelona, San Sebastián, and Zaragoza. This columnist attended the concert at Madrid’s Palacio de los Deportes and witnessed something he doesn’t recall ever having seen again: in a packed arena, a large portion of the audience began to boo the band for their self-indulgence in selecting the setlist. They began with a long acoustic segment, and more than half the songs they performed belonged to the two Machina records. When the big hits finally arrived, they failed to redeem the Pumpkins from the general boredom they had caused.

On December 2, and with considerably more glory, the band officially bowed out at Chicago’s Metro Hall, the same venue where they had begun their career 12 years earlier. It was a concert that lasted four and a half hours. Each attendee was given a CD that included a recording of their first performance at that very venue. That would have been an excellent end for the band if not for one important detail: it wasn’t the end.

The erratic Pumpkins of the 21st century and an unexpected reissue

After the group’s dissolution, Corgan and Chamberlin formed a short-lived alternative super band called Zwan — Spain witnessed one of their rare concerts at Madrid’s La Riviera in 2003 — and the vocalist subsequently released his only solo album, The FutureEmbrace.

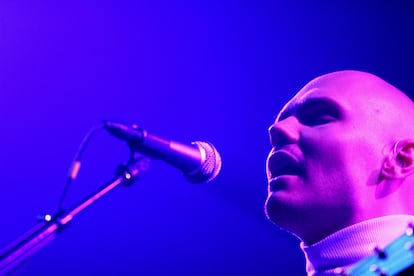

Smashing Pumpkins’ silence lasted only seven years. In 2007, they returned with a new album, Zeitgeist, although only the singer and drummer from the original lineup remained. Both the album and the tour were flops, but their free fall into irrelevance and public disinterest accelerated with their subsequent releases.

Oceania (2012) and Monuments To An Elegy (2014) were originally scheduled for Teargarden By Kaleidyscope, another ambitious conceptual project that remained unfinished, with Corgan now the only founding member. Chamberlin and Iha returned for Shiny and Oh So Bright Vol. 1 / LP: No Past. No Future. No Sun (2018) and Cyr (2020), and for a lengthy new release titled Atum: A Rock Opera in Three Acts (a trilogy of albums to be released between 2022 and 2023). Their latest album to date is Aghori Mhori Mei, which was released last August.

In reality, the entire strange trajectory of the 21st-century Smashing Pumpkins, much closer to a screwed-up Tool or Pink Floyd than to, say, Nirvana and Pearl Jam, is a diminished continuation of what they ventured into with the two volumes of Machina. In that sense, that project didn’t so much mark the end of the band as the beginning of a new Pumpkins that, moreover, has lasted longer than their triumphant first incarnation in the 1990s.

Corgan, in fact, has never stopped defending their two 2000 albums, which he considers a manifesto that defied the path that would have been easier for them and the one that would have pleased fans and the industry: that of repeating themselves. So much so that the musician has been working for years on a reissue that shows the project in a way that is more faithful to how he originally conceived it, including the simulation of a concert with canned audience noise (in the style of the album Alive! by his admired Kiss).

The first news about it dates back to 2011, but legal issues with the record company have been delaying it. In 2021, in an interview with New Musical Express, Corgan stated that the reissue was already finished and would contain more than 80 songs, but, to date, nothing further is known about it. Another unfinished and long-delayed project is his equally ambitious book of “spiritual memoirs,” influenced by Herman Hesse’s Siddartha (1922), which would be titled God Is Everywhere, From Here to There, and for which he says he has already written more than 1,000 pages.

Recently the musician declared on The Joe Rogan Experience podcast that Smashing Pumpkins were “one of the most misunderstood bands in the history of rock and roll,” and he also expressed disappointment that they haven’t been given enough credit for paving the way for bands like Muse.

For now, his latest announcement is that, in November, the band will celebrate the 30th anniversary of Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness by performing the entire album with a symphony orchestra for seven nights at the Lyric Opera of Chicago. Corgan’s intention with this is to appeal to both rock and bel canto audiences, but it’s really hard not to see it as the self-parody he promised to play 25 years ago, which ended up swallowing up one of the most talented musicians in alternative rock.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.