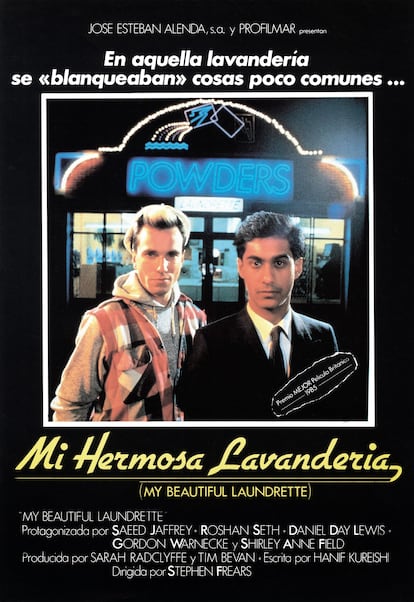

Gay far-right sympathizer falls in love with young Pakistani man in Thatcher’s London: The magnificent 40th anniversary of ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’

Daniel Day-Lewis, Hanif Kureishi and Stephen Frears were almost unknown when they burst onto the scene with this low-budget English film

There are blockbusters that flop before reaching the screen. And then, there are independent gems that become huge, thanks only to word of mouth. My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), now 40 years old, is an extreme example of this second category. At first, it didn’t even aspire to reach theaters, yet it became an international hit and a fixture on lists of the best British films, in addition to catapulting the careers of many of its creators. And it did all of this with a seemingly conflictive story, filled with social criticism, barbs at English classism, and queer themes.

My Beautiful Laundrette tells the story of Omar. The son of Pakistani immigrants in South London, he doesn’t want to end up like his father, a failed left-wing journalist, disillusioned by English society. Omar prefers to stay with his uncle Nasser, a successful businessman with a double life: at home, he acts like a classic patriarch, while outside, he maintains an English mistress and frequents dance halls.

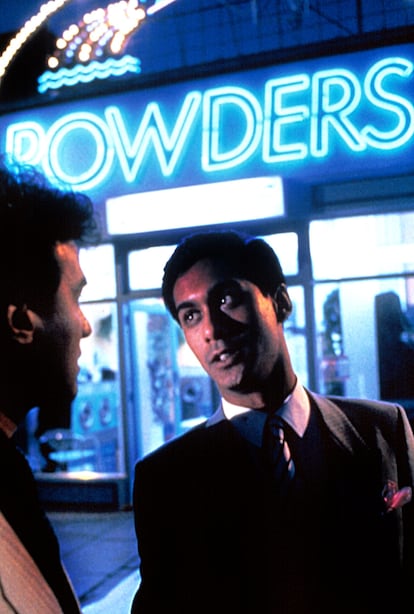

One night, Omar reunites with Johnny, a white childhood friend who has become a skinhead. They both realize they’ve become the opposite of what they once were because of their society’s contradictions: one, racialized, has become a cynic who only believes in money, while the other — who hails from the working class — blames everything on immigrants. Acknowledging all this brings them closer together… and they resume the love they had for each other as teenagers. In the process, they agree to modernize and run a laundromat that Nasser uses to “launder” the money he earns from drug sales. Obviously, everything ends up shattering (including the laundry’s window) in an ending that’s as happy as it is cynical.

For the British Film Institute (BFI), it’s one of the 100 best British films of the 20th century. And it’s also on the BFI’s list of the 30 best films with LGBTQ+ themes. But the story of how it came to be filmed and how it reached movie theaters around the world is as fascinating as the fate of its creators and protagonist.

In 1982, the British parliament approved the creation of a new free-to-air television channel, in order to break the duopoly between the state-run BBC and the commercial channel ITV. The new channel would be required to meet certain public service objectives — representing national diversity, instilling innovative and educational values, as well as cultivating a distinct personality — but with two fundamental economic conditions: it had to be self-funded, through advertising (a prime example of Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal policies) and it could not produce its content internally. Instead, it would have to commission it from private British production companies.

The result — Channel 4 — proved to be a resounding success. The desire to pursue quality and a unique catalogue, along with the need to be commercially viable, has ensured that it remains one of the three most-watched channels in Britain. It’s also one of the outlets that wins the most awards.

Thanks to Channel 4, series such as Queer as Folk, Black Books, Misfits, Utopia — and, more recently, Shameless, Derry Girls, and Black Mirror — have been produced. The formula is clear: don’t shy away from politically risky topics, give space to creativity, and ensure solid, high-quality productions. But that’s only in the present, with a well-established record. 40 years ago, the production team didn’t know where to start.

It was at this time that Tim Bevan and his then-partner Sarah Radclyffe entered the scene. They had set up a music promotion company in the early 1980s that recruited young filmmakers to make the essential music videos of the MTV era. The transition to filmmaking seemed obvious. Hence, they decided to found a production company that they called Working Title. They were immediately commissioned to develop a feature film for Channel 4 that would reflect the network’s values of diversity, topicality, and public service.

In an interview included in the DVD extras released by the Criterion Collection, Radclyffe recalled those years: “Channel 4 is the best thing that’s happened to our generation. For us, the BBC was the establishment, [while] ITV was a combination of companies, which made it difficult to work in that environment. Channel 4 was different, exciting. It was our voice, our generation. You could take risks and tackle political topics.”

For the plot, Bevan immediately thought of a young Pakistani writer he had recently met, who wrote short but poignant plays for independent venues.

Hanif Kureishi was 20 years old at the time. The son of an immigrant from Pakistan and an English mother, he had experienced racism and class divisions between his traditional family environment and a class-ridden country marked by the ruptures of punk, the economic crisis of the 1970s and the anything-goes of Thatcherism. Bevan asked Kureishi for a script and then called up Stephen Frears — who had experience at the BBC and two more or less unsuccessful crime films under his belt — to direct the movie.

Kureishi poured all his personal experiences into the story: from the strict codification of the Pakistani family structure to the racism of skinheads on the streets; from drug dealing to gentrification; from the shattered hopes of the Labour Party to the capitalist voracity of Thatcherism. He even incorporated biographical anecdotes and moments from his own life.

“I had an uncle who would take me around [his] laundrettes… because I think he thought the writing business was probably never going to work out,” he said, in an interview with the British Library. To give the project a standard structure, he conceived it as a classic “buddy movie,” a film about colleagues, a subgenre in which Frears could feel comfortable.

But if there’s one thing that defines the film, it’s cynicism — something that handily portrayed the society of the time.

“Stephen told me: ‘Make it dirty,’” Kureishi recalled, in an interview with The Guardian. “That’s a great note. Writing about race had been quite uptight and po-faced. You saw Pakistanis or Indians as a victimized group. And here you had these entrepreneurial, quite violent Godfather-like figures. He also kept telling me to make it like a western.”

The big themes are all there: racism, gentrification, class violence, homophobia, sexism, rampant capitalism, the loss of values and ideals. In the year of its release, Frears told The New York Times that the film offered “a good picture of Britain: isolated communities, somehow exploiting the situation — the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer; people struggling to maintain private values and dignity. The problems in England are terrible, and you don’t hear the sound of laughter in Britain.”

The theme of London’s gentrification has been so evident that the British Film Institute produced a report on the “then-and-now” locations of the film: from the dirty, drab, 1980s derelict structures, to immaculately clean properties, landscaped and ready to be photographed for a real estate magazine. The only thing missing is the laundromat: a block of flats has now been built on the site.

The film neither resolves nor condemns the problems it portrays, nor even attempts to judge them. In the end, things work out, with all the characters reconciling and resolving their differences… but at the cost of looking the other way and profiting from the situation. As film historian Pam Cook notes: “The strength of My Beautiful Laundrette is that it asks difficult questions in a provocative and entertaining manner, managing to be critical and sympathetic at the same time.”

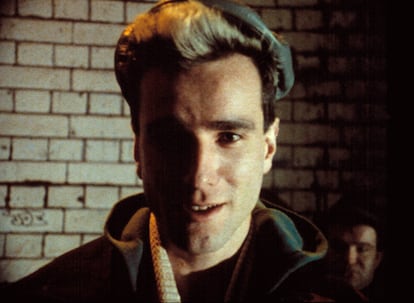

The shoot was quick, straightforward and inexpensive, with a mix of established actors of English, Pakistani and Guyanese descent, as well as new faces. The most striking role — that of Johnny, the tormented gay skinhead — was rejected by two actors who were just starting to attract attention: Gary Olman and Tim Roth. Ultimately, the role ended up in the hands of a complete unknown… one Daniel Day-Lewis. That same year, he also shot another small production in which he played the most polar-opposite character imaginable: Helena Bonham Carter’s uptight and posh fiancé in A Room with a View (1985). Both films were released almost simultaneously.

My Beautiful Laundrette would take a while to reach the television version for which it was conceived. At its premiere at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, it was so highly praised that the production company — Working Title — decided to expand it from 16mm to 35mm and release it in theaters. It became an immediate success, earning $3 million at the box office against a budget of just £600,000 (or $817,000). It was recognized in several award categories, with Kureishi nominated for Best Original Screenplay at the British BAFTAs and the Oscars. The applause was almost unanimous. And it also provided a fundamental boost to the careers of almost everyone involved.

Kureishi subsequently published his most influential novel — The Buddha of Suburbia — in 1990, which was followed by several hits that established him as a provocative and widely read author. His opinion on cinema hasn’t changed, as he made clear in recent statements to Sight and Sound magazine: “Contemporary independent film should be dealing with what life is like in Britain today. So much drama on television is dire — sentimental and nostalgic. I wanted to do something hard.”

Frears, in turn, would soon launch into big-budget projects, such as Prick Up Your Ears (1987) — a biopic of the gay playwright Joe Orton — as well as Dangerous Liaisons (1988). However, Frears would clash with Hollywood in the final years of the 20th century with films that were too sophisticated for the American industry. The failure of Hero (1992), starring Dustin Hoffman and Geena Davis, was followed by Mary Reilly (1996), Julia Roberts’s first attempt at a serious role. He subsequently made a series of small productions — some more personal than others — until The Queen (2006) arrived… that strange justification of Elizabeth II’s behavior following the death of Lady Di, which would bring him another worldwide hit. He would then resign himself to making eminently British commercial films, including Philomena (2013), Florence Foster Jenkins (2016) and Victoria & Abdul (2017), works that praise the English establishment. A curious ending, indeed, for someone who began his career criticizing it.

Something similar — but on a much larger scale — would be the fate of the production company behind My Beautiful Laundrette. Working Title has been responsible for some of the most commercial titles of the last 40 years, specializing in the English romantic comedy subgenre and making a fortune along the way. For Variety magazine, it is “arguably the U.K.’s best known and most successful production company.” In 1994, it released Four Weddings and a Funeral, the smash hit that would create the house brand and begin the production team’s collaboration with director Richard Curtis. This union would yield fruits such as Notting Hill (1999), the successive installments of Bridget Jones’s Diary, as well as Love Actually (2003).

Even though Working Title has produced films by the Coen brothers, Derek Jarman and Ken Loach — and, more recently, The Substance (2024) and The Brutalist (2024) — their catalogue since 2000 has focused on a recognizably English type of cinema, including gentle films and literary adaptations like Billy Elliot (2000) or Pride and Prejudice (2005), as well as period pieces, such as Mary Queen of Scots (2018). Working Title was created to produce films that reflected the political and social reality of the UK… but it has ended up becoming a factory of sugarcoated clichés about everything English.

Without a doubt, the most important of the careers that took off in 1985 with My Beautiful Laundrette was that of Day-Lewis. Considered “the best actor in the world” after winning his third Oscar, over the years he would go on to play such celebrated roles as the protagonist of My Left Foot (1989), who suffers from cerebral palsy; a man falsely accused of belonging to the IRA in In the Name of the Father (1993); Nathaniel “Hawkeye” Poe in The Last of the Mohicans (1992); and the faint-hearted representative of the New York gilded age in The Age of Innocence (1993).

Day-Lewis dominated the screen in the 1990s. And, since then, between retirements in Florence, he has reappeared periodically. And when he does, awards rain down on him: three Oscars, three Golden Globes and four BAFTAs are proof of that. Anemone (2025), co-written with his son, who also directs the film, is still pending release.

The fate of My Beautiful Laundrette is an interesting case. A socially critical, politically committed film, it touches on each and every one of the sore points of English society with absolute precision. It was never intended to reach theaters, and yet, it became the starting point for the most successful style of commercial cinema in the following decades. But even more surprising is its relevance 40 years later. Having become a milestone in queer cinema, it remains as fresh and poignant as the day of its release.

Today, there are more and more multiracial countries in Europe. There are several generations of children of emigrants who are torn between two cultural models. People are living in rapidly gentrifying cities, while the far-right is feeding off the disillusionment of the working class and scapegoating immigrants and the LGBTQ+ community. Under these circumstances, it’s time to watch the film again, to confirm that it’s still relevant.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.