‘Absolute and utter rubbish’: When ‘Four Weddings and a Funeral’ was slammed by its own cast

The romcom classic, starring Hugh Grant and Andie MacDowell, brought comedy laced with cynicism into the mainstream, but no one involved believed it would work

Thirty years after its premiere, director Mike Newell remembers Four Weddings and a Funeral as a train that arrived at its destination on time, after being on the verge of derailing at almost every station in between. The veteran director was especially mortified by the paltry £3 million ($3.8 million) available to him which he believed to be totally insufficient to put together a romantic comedy that was “very ambitious, with dozens of characters and five different environments.”

By the 30th day of shooting, Newell was down to his last penny and had yet to resolve one of the four weddings and a romantic climax he envisioned as spectacular, with the camera looking down on Hugh Grant and Andie MacDowell for a rain-soaked overhead shot as they come together. That scene — like many others — is not in the film. The idea had to be replaced by a much cheaper and more conventional succession of shots and counter-shots between MacDowell and Grant that, in spite of everything, is now studied in film schools as a prime example of a classic denouement.

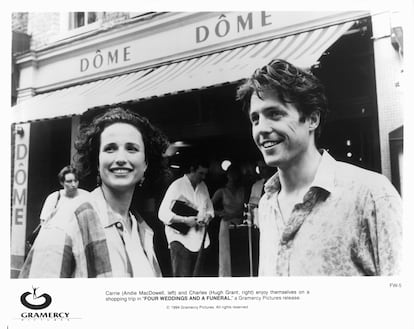

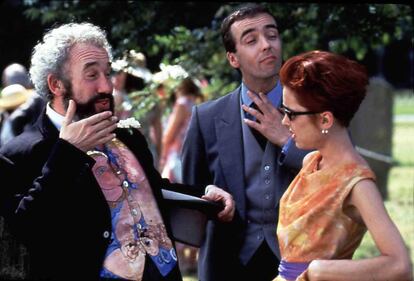

Success stories can be deceiving. Today, we know that Four Weddings and a Funeral was destined to multiply its modest initial investment by 50 and gross an impressive $245 million. It turned Hugh Grant into a star and the intense, mournful Andie MacDowell into the new romcom queen. And it put Kristin Scott Thomas on the Hollywood map at last as well as introducing talented supporting actors such as Simon Callow, Charlotte Coleman and John Hannah while breathing new life into Mike Newell’s career. Significantly, it transformed its screenwriter, Richard Curtis, into one of the industry’s heavyweights as it swept the BAFTAs, competed for Academy Awards and rivaled some of 1994′s best movies, such as Pulp Fiction, Ed Wood, Shawshank Redemption, Natural Born Killers, Clerks, The Lion King and Forrest Gump.

It also proved that British popular comedy could once again be a viable global export, and it made ephemeral fashions out of unlaudable qualities such as ostentation, snobbery and sarcasm, judiciously sweetened by a healthy dose of giddiness and social awkwardness. From a corporate point of view, it cemented the immense prestige of the production company Working Title and its continental partner, the Dutch distributor PolyGram, which would soon rub shoulders with the big Hollywood studios.

This is how history is written

Since all that happened — and weighing up the quality of the film, it seems logical it did — we tend to think it was inevitable. But it is enough to read what Newell, Curtis, Grant and the film’s producer, Duncan Kenworthy, have been recently saying about the movie as it reaches its 30th anniversary, to see that the main figures behind this sardonic comedy were not at all sure that they had a winning horse in the stable.

Shortly before the film’s release, Kenworthy was wondering if Richard Curtis’ original screenplay would not have been better served by a director with a less stuffy and more “contemporary” touch than Mike Newell, whose credentials stretched to directing Miranda Richardson in Enchanted April. Kenworthy was also concerned that the cast did not include any major stars, beyond a famous but unappreciated Andie MacDowell; and that the role of Charles, the character who made the expression “serial monogamist” fashionable, had fallen into the hands of a then only promising Hugh Grant, after more obvious options such as Alan Rickman and Jim Broadbent had had to be shelved.

Curtis wasn’t entirely sold on Grant (“I thought he was too handsome, too young and too devoid of the veneer of exquisite cynicism I envisioned for Charles”) and was disheartened that MacDowell, particularly in the wake of the success of Groundhog Day, had been cast as a last-minute replacement for the actress Marisa Tomei, who Curtis wanted for the role. Tomei eventually did accept the part and planned to move to England in the spring of 1993 to begin working on the movie, but a family issue forced her to change her plans.

As for Newell, his main concern, as he explained to media such as the Evening Standard, was to complete the film in the six weeks planned “without any deaths or injuries.” This was not in fact said as a joke, or at least not entirely: the London filmmaker claims that Hugh Grant and Charlotte Coleman risked their lives during the filming of a scene whose calibration was haphazard, to say the least

The scene in question involved Charles and Scarlett who were about to be late for the first of the ceremonies and decided to drive a few meters backwards to take a detour even though a truck was speeding towards them: “That scene on the motorway, for some reason, Hugh was actually driving. He shouldn’t have been, but he was. They were within inches of backing at full speed into a truck that was coming at them,” Newell told The Guardian. Newell had a moment of painful lucidity in which he saw himself accompanying the actors to hospital in an ambulance, with the shooting canceled and a letter of dismissal under his arm. “I suddenly saw the whole film collapsing in front of me, and what I had done was engineer the death of the leading man on the motorway,” he said.

In an interview with the SAG-AFTRA Foundation, Grant himself recalled that the first private screenings of the film, with a tentative edit that apparently convinced Newell but not Curtis or Kenworthy, proved a failure: “I thought we’d screwed it up. When we went to watch a rough cut, all of us, me, Richard Curtis, Mike Newell, the producers, all thought this was the worst film that’s ever been perpetrated,” said Grant. “We’re going to go and emigrate to Peru when it comes out so no one can actually find us.”

New Zealand actor Sam Neill explains in his autobiography that his good friend Grant told him in the spring of 1994 that he had just shot a movie that was “a piece of complete crap.” He reportedly described the film as “absolute and utter rubbish,” and predicted fierce criticism and the unconditional hatred of almost any viewer with a minimum of criteria. “I’m afraid I’ll never recover from this one,” he reportedly told Neill.

The moment of truth

Grant was wrong. Somehow, the film was rescued against the odds on the editing table and presented with full honors in January 1994, at the Sundance Film Festival. Early reviews were enthusiastic. Sensing its potential, PolyGram and international distributor Rank Films insisted on releasing it first in the U.S., albeit in limited cinemas, like someone dipping their toe in the ocean to test the water.

On March 11, it was released in five theaters in New York and Los Angeles. It was so overwhelmingly successful that an ambitious $11-million marketing campaign was launched two weeks later. The film ended up landing back in the U.K. in mid-May. By August, it had made close to $100 million at the box office and had become something of a phenomenon, trumping comedies such as Ace Ventura and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. Only The Mask, released shortly after, would come close, but the Jim Carrey film had a $23-million budget.

It is often said that failure is an orphan and success has many parents. Paul O’Callaghan, a film critic with the British Film Institute, believes that in the case of Four Weddings and a Funeral, Curtis’ seamlessly witty script, Grant’s iconic performance, the exceptional supporting cast and the fact the soundtrack featured the Troggs’ Love Is All Around in a version by the Scottish band Wet Wet Wet, were key ingredients of the winning recipe.

Curtis, in particular, created a memorable ecosystem of characters and knew how to pepper his script with brilliant repartee and biting observations on life, death, love and marriage. He also had the good sense to call on an old accomplice, Rowan Atkinson, for the scene with the trainee priest who officiates at his first wedding and is unable to string together more than four meaningful words. Atkinson and Curtis had worked together on scripts for Blackadder and Mr. Bean, and the screenwriter considered the comedian the best insurance policy the film could hope for: even if it turned out to be a disaster, they could always count on Atkinson’s fans to go see it.

For musician and culture journalist Bob Stanley, the success of a popular comedy will always depend on contextual factors and its ability to tune in to contemporary culture. In the case of Four Weddings and a Funeral, Stanley points out that it was released in the summer of 1994 when young political upstart, Tony Blair, assumed the leadership of the Labour Party, a band from Manchester called Oasis released its first album, Definitely Maybe, and a new aesthetic trend, labeled Britart, burst into galleries and museums driven by “tawdry and outrageous young talents” such as Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin.

In this context of New Labour, friendly Englishness, festively belligerent art and British pop that boasted an international projection despite its arrogant insularity, Four Weddings and a Funeral unexpectedly hit its target because it was timely and, moreover, it had substance, it had roots and it made perfect sense. Hence, its triumph, attributable also to a tragic phrase, rescued from a poem by W.H. Auden — “He was my North, my South, my East and West” — and to dialogues as hilarious and credible as this:

Charles. How do you do, my name is Charles.

Old man. Don’t be ridiculous, Charles died 20 years ago!

Charles. Must be a different Charles, I think.

Old man. Are you telling me I don’t know my own brother!

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.