‘My plan was not to join Hollywood. It was to destroy it’: How Jim Carrey triumphed through anarchy

In February 1994, ‘Ace Ventura: Pet Detective’ arrived to U.S. theaters, catapulting its star to global fame. After tiring of retirement, he’ll return this year to act in ‘Sonic 3′

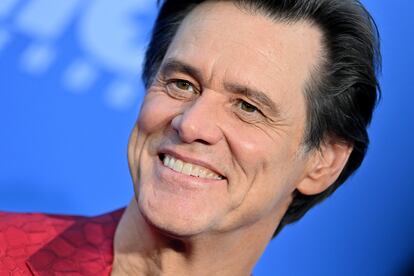

Sean Connery decided his final film would be The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003). Gene Hackman bid adieu with the lackluster Welcome to Mooseport (2004). And two years ago, Jim Carrey (Ontario, Canada, 62 years old) purported that he would become a member of this club of legends who ended their careers on an anticlimactic note when, the day before the premiere of Sonic 2: The Movie in April 2022, he surprised the world with the news that he was retiring. “I have enough. I’ve done enough. I am enough,” he said in an interview with Access Hollywood. “I’m being fairly serious. I really like my quiet life and I really like putting paint on canvas and I really love my spiritual life.” Nonetheless, the comedian left the door open to a comeback: “If the angels bring some sort of script that’s written in gold ink that says to me that it’s going to be really important for people to see, I might continue down the road.” Just a few weeks ago, that project capable of bringing Carrey out of his exile arrived: it has been announced he will appear in Sonic 3.

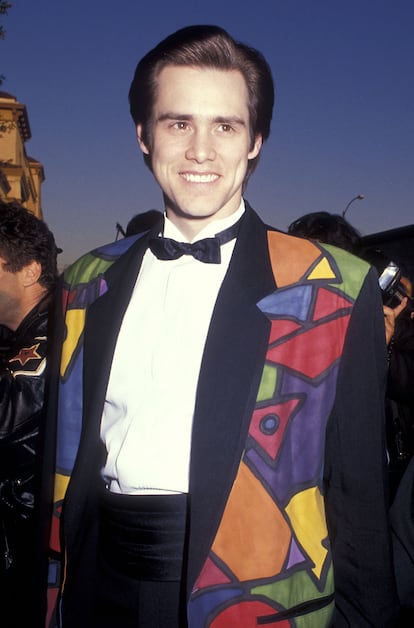

In addition to sowing sky-high expectations about the script of the third installment of the saga, based on the Sega video game, the confirmation of the end of Carrey’s retirement coincided with the 30th anniversary of Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, the film that catapulted Carrey to fame after its February 1994 release. The comedy (and character) opened a glorious year for the actor, who within just a few months would release two other phenomenal films in The Mask and Dumb and Dumber. The next year, he played the villainous Riddler in Batman Forever, filmed the sequel Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls, and by 1996, was the highest-paid movie star in the world, thanks to the $20 million fee he received for The Cable Guy.

The rest is history. The very embodiment of the sad clown cliché, Carrey felt the need to be recognized as a dramatic actor, and starred in prestige projects like 1998′s The Truman Show and 1999′s Man on the Moon, a change-up for which he was pardoned by critics. The Academy, however, offered no such consolation, and he was never nominated for an Oscar. His biography is marked by struggles with depression, from which he said he recovered in 2017, but that which may have been linked to relationships that quickly evaporated and the suicide of an ex-girlfriend who had been 23 years younger than the actor, carried out with pharmaceuticals that had been prescribed to Carrey. He had an anti-vax stage and another dedicated to political satire that peaked with confrontations with both Trump and Mussolini’s granddaughter. Where he has enjoyed some success is in the arena of self-help, thanks to his penchant for motivational speeches and inspirational yarns, such as his oft-repeated tale about how in 1985, he wrote himself a check for $10 million to convince himself that someday, he’d earn the staggering amount. He carried it around until cashing it, a decade later, for Dumb and Dumber To.

Carrey’s trajectory has managed to be both stranger and more erratic than that of your typical star. His filmography became less consistent after his first decade of success, and Carrey has played with his public image in disconcerting, if not uncomfortable, interviews that leave the line between performance and real jadedness unclear. This legend became further exaggerated in 2017 with the release of the documentary Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond, which was composed of material that, according to the star, Universal had saved since the end of the ‘90s, “so that people wouldn’t think Jim is an asshole”: footage from the filming of Man on the Moon, where for weeks he sewed chaos with his round-the-clock impression of the character he played, alt comedian Andy Kaufman. In addition to sparking debates over method acting (the documentary included moments of violence, with Carrey at one point being knocked unconscious in a fight, which left his co-stars visibly upset), the film renewed interest in the destabilizing undercurrents of Carrey’s humor, and opened up other avenues towards understanding his legacy.

Containing multitudes

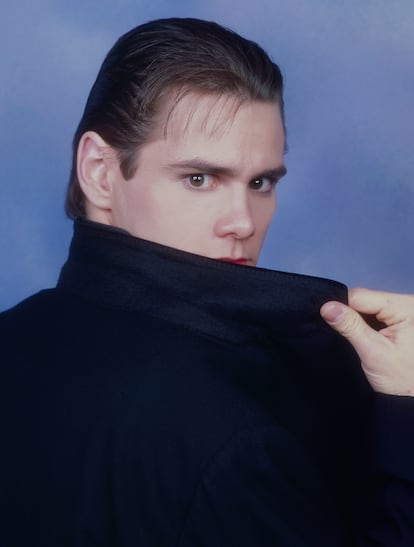

The rise of Carrey in 1994, after years of attention-grabbing sketches and supporting roles, coincided with the heyday of grunge (it was the same year that Kurt Cobain committed suicide), making for a confluence of generational happenings that now seem irrevocably linked. The first installment of the Ace Ventura series, whose script was co-written by Carrey, presented a screaming, energetic, irate, endlessly voluble character who ridiculed the serious adults around him and literally, talked out of his ass. It was a parody of thriller movies — its transphobic denouement, which has aged terribly, is a nod to Dressed to Kill (1980) and Silence of the Lambs (1991) — the movie told the story of a detective specializing in animals who was tasked with tracking down a NFL team’s kidnapped dolphin mascot on the eve of the Super Bowl.

Carrey’s gift for transforming his face, body and voice at top speed encouraged comparisons of his work with that of Tex Avery, whose violent and histrionic cartoons served as the inspiration of The Mask. All three movies in which the actor starred in 1994 were adapted into animated series. Finnish academic Tarja Laine published an article in 2001 in the magazine CineAction called The King of Embarrassment, in which she studied the source of the actor’s comedy.

“Carrey is sociologically provocative because his comic art is based on shame and embarrassment created by a tension built in social interaction,” Laine wrote. “In the same way as Jerry Lewis, by masochistically making embarrassment and self-humiliation the basis of his comedy, Jim Carrey turns the entire process of bourgeois subject formation inside out. The embarrassing pleasure that is being evoked in the films of Jim Carrey seduces the spectator to participate in this abandoning of the stability of the ego in a spectacle of abjection that stirs delightful fantasy.”

The critic admitted her disappointment with the dramatic shift in the roles that Carrey chose, whose dilemma she saw embodied in Me, Myself & Irene (2000). In that Farrelly brothers comedy, a repressed police officer suffers from a split personality from which emerges a chaotic and aggressive alter ego that he has to fight to contain. “Jim Carrey’s career is in the same kind of crossroads of two screen personalities. But it is still left unseen, which personality will finally conquer: the conventional or the anarchistic one?” Contacted by EL PAÍS 23 years later, Laine, who is now a film studies professor at the University of Amsterdam, laments that neither side of the actor ever claimed victory: “The fact that he did not get an Oscar nomination for his roles in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) or Man on the Moon can be seen as a symptom of Hollywood’s rigidity. It’s a shame that he didn’t go on to do any more serious roles, given that the majority of his comedies were formulaic and he’s now acting in a video game franchise. That could be due to a poor job on the part of his agent or personal reasons.”

“What Carrey did that was unique was his ability to extract humor from situations that weren’t necessarily funny, above all from negative or uncomfortable emotions,” she tells EL PAÍS. “He did something similar to what the Farrelly brothers try to achieve with their films: a carnivalesque liberation of behavior norms, in the spirit of Mijaíl Bajtín [the Russian thinker for whom popular slapstick expressions represented opposition to the aristocracy’s rigid views].

The infinite jest

In an extensive Rolling Stone profile published in 1995, journalist Fred Schruers had the opportunity to portray the Jim Carrey who was settling into Hollywood, through an interview conducted amid the filming of Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls. The article also quotes the wife who Carrey was divorcing after eight years of marriage, and with whom he had a daughter in 1987. Melissa Womer claimed that the man to whom she was still married suffered from severe depression and that he regularly stayed up crying until the wee hours of the morning: “I’m nervous for him. I think creative people need to be aware of the dark side that accompanies those gifts they have. I’ve learned that the smile he wears is the biggest mask of all.”

“I don’t think there can be a creative person on earth who doesn’t have extreme highs and lows,” responded Carrey. “Otherwise, you’re just boring. Some of the best work I’ve ever done has come out of those lows.” The Rolling Stone article delved into the legal battle for his estate, with Womer’s lawyer claiming that Carrey did not want to grant her an amount that he could earn with a few days’ work due to family trauma: his father had been unemployed and penniless throughout Carrey’s adolescence. The actor says his first experiences with violence took place during that time, when he and his brother vandalized the factory where his father had been exploited. Carrey said in the piece that he had supported his family financially for years, which had caused him to have recurring dreams in which he strangled his mother.

In v published by The Hollywood Reporter and written by Lacey Rose in 2018, he seemed to be more at peace. He was promoting the series Kidding at the time, his first work of fiction since the suicide of his ex-girlfriend. With the role of a children’s television host in the middle of an existential crisis, director Michel Gondry tapped into a personal moment for Carrey, similar to when he recruited the actor for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, which involved a visit to Carrey on the set of Bruce Almighty (2003) and found him bereft over his breakup with Renée Zellweger. “My plan was not to join Hollywood. It was to destroy it,” the actor reminisced, recalling his career’s early days. “Like, take a gigantic sledgehammer to the leading man and to all the seriousness.” The interview insisted that he was loath to return to Hollywood’s frontlines.

Nonetheless, the Sonic movies (from 2020 and 2002) have become two of Carrey’s biggest commercial hits. His character Dr. Robotnik has allowed him an unexpected comeback to an acting style along the lines of The Mask, excessive and caricatured. In the book Memoirs and Misinformation (Knopf, 2020), which he co-wrote with Dana Vachon, Carrey establishes his professional point of no return as having been I Love You Phillip Morris (2009) which had distribution problems due to, among other factors, a scene in which he is seen having anal sex with Ewan McGregor. Due to this, the actor says that Disney and Paramount put their projects with him on ice and suggests that his agents forced him to do Mr. Popper’s Penguins (2011) because, according to them, Ace Ventura proved that “people love seeing him with animals.”

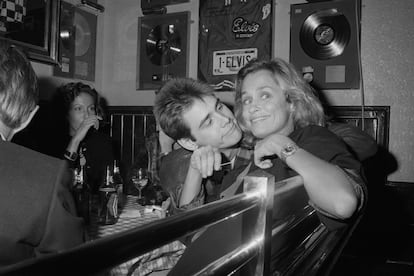

As with so many other factors related to Carrey, it’s difficult to know how much truth there is to this: the book is a fictional novel featuring aliens, sprinkled with biographical facts (the story of the dreams in which he strangles his mother makes a reappearance) and tales of his great loves such as Linda Ronstadt — with whom he had a relationship when he was young and she was a full 15 years older — and Renée Zellweger — who is fancifully depicted as having left him for the bullfighter Morante de la Puebla. Ultimately, a cataclysm leads him to experience an epiphany that undoes his individual identity. This seems to be in tune with an introspective interview he gave to Jimmy Kimmel in 2017: “Don’t get me wrong, Jim Carrey is a great character, and I was lucky to get the part. But I don’t think of that as me anymore.” “I hear people say, ‘Why doesn’t he just be funny?’ That stuff has just never mattered to me,” he elaborated in The Hollywood Reporter. “To me, it’s like, this is the experiment tonight. If you enjoy it, great, if you don’t, that’s cool, too. There’ll be another one tomorrow.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.