What if ‘Groundhog Day’ talks about all of us? An investigation into the most famous time loop in cinema

Critics Santiago Alonso and Isabel Sánchez have published an essay on the comedy starring Bill Murray that went on to gain cult status, generate imitations, and raise existential questions 30 years after its release

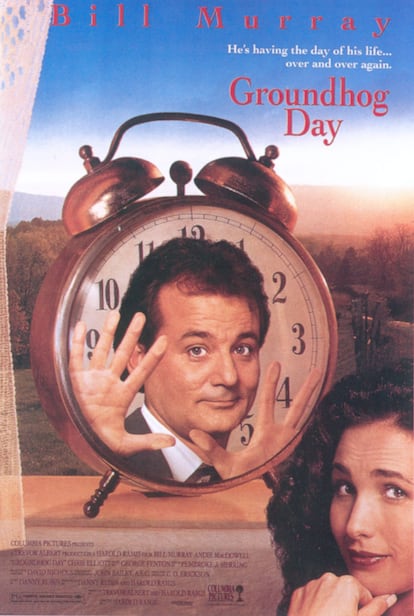

What does “Groundhog Day” mean to you? If the phrase automatically leads you to think about the same day repeating itself over and over again, it is thanks to the 1993 movie of the same name, which is one of the most influential comedies of recent decades.

The film’s title comes from a real life annual tradition, celebrated in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania on February 2. Groundhog Day is the day when, according to a Pennsylvania Dutch superstition, a groundhog known as Punxsutawney Phil predicts how long the winter will continue, based on whether or not he sees his shadow when he emerges from his burrow in the morning.

The movie follows the misadventures of surly meteorologist Phil (Bill Murray), who has been sent to broadcast from the Pennsylvania town on the eponymous Groundhog Day. However, after he finishes recording his segment, he is forced to spend the night in the town due to bad weather. To his horror, when he wakes up, it is February 2 again, and nobody has noticed except him. The same happens the next day, and the next, and the next. And so on indefinitely.

Directed by Harold Ramis, Groundhog Day became an instant classic and spawned an ever-increasing number of films in the same narrative mold, such as Edge of Tomorrow (2014), Happy Death Day (2017), and Palm Springs (2020). It also became an inexhaustible source of analysis, theories, and all kinds of literature.

One such study is the recently published Prisioneros del bucle (Prisoners of the loop), a Spanish-language essay in which journalists and film critics Santiago Alonso and Isabel Sánchez delve into the key elements that made Groundhog Day a cultural phenomenon. “It’s sobering to think that a film from only 30 years ago has given rise to so many others that copy it or are based on it. There was something to research,” Alonso tells EL PAÍS. For the co-author, the reasons for the study’s validity are clear: “It is due to the philosophical depth of its topic. Any viewer can identify and become hooked on its existentialist perspective. And, above all, the idea behind the plot is great.”

In one of the scenes in the film, Phil shares his affliction with the patrons of a bowling alley and, after asking them what they would do if their life was stuck in a place where every day is the same and nothing you do matters, one responds: “That’s the story of my life.”

“In middle age, we often get bored with our own lives, it seems like we are repeating the same day over and over again,” Isabel Sánchez reflects. The writer admits that what interested her most about the comedy is its nature as a fantastical love story that develops over time, which puts it in the orbit of classic films such as A Matter of Life or Death (1946), The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), and Portrait of Jennie (1948). After all, the role of Rita, the producer played by Andie MacDowell, is essential for Phil’s transformation.

“When Rita tells him what her perfect man would be like, she unknowingly becomes his guide and draws him a map,” the journalist explains. “It makes him realize that he is an asshole but he can take a path to become better, to see that life can be something else, and to learn to enjoy it as part of a community.”

Prisioneros del bucle is made up of a first part that tells the story of the production of the film, a second based around the literary and cinematographic background and its philosophical interpretations, and a third where the two authors dialogue about other movies involving time loops.

Jon Mikel Caballero, director of the Spanish movie The Incredible Shrinking Wknd (2019), features in the book with a final interview, as does the screenwriter of Groundhog Day, Danny Rubin. The Californian playwright says that the idea for the story came to him from the novel The Vampire Lestat (1985), by Anne Rice. “The universe Rice had created included people who were exactly like us, except in a few things. One of them was that they were always the same age and lived forever. That’s what I started thinking about that day,” Rubin clarifies in the book.

The film was a huge box office success in 1993 but also marked the end of the friendship and collaboration between Ramis and Murray. Both had worked together on Meatballs (1979), Caddyshack (1980), and Ghostbusters (1984), movies that are considered to have contributed to transforming the codes of American comedy of their time.

However, Murray’s stress over his divorce during the filming of Groundhog Day and the creative differences between the two (apparently Murray, who was looking for a career change, advocated a more tragic original version of Rubin’s script, while Ramis turned it into a romantic comedy) created an extremely tense atmosphere. According to the book How to be Bill Murray (Gavin Edwards, 2016), the actor stopped speaking to Ramis and hired a deaf-mute interpreter to mediate between them using sign language. They did not speak again until Murray decided to visit the terminally ill filmmaker shortly before his death in 2014.

“It was always said that, of the two, Bill Murray was the one who threw the map out the window and Harold Ramis was the one who looked for a way to get home,” says Sánchez. “That’s why they worked so well as a duo, one was chaos and the other was order.”

For Alonso, “it is not worth it” to think about what the film would have been like if that more dramatic vision that the screenwriter and Murray initially advocated had been imposed: “What matters is what it was. If one of the parts of the whole had been different or was made differently, perhaps we would not be talking about the same film.” Sanchez also vindicates Ramis and his sense of lightness: “He achieved a very difficult balance between comedy, romance, and thematic depth. Curiously, despite how light it appears to be, it has given philosophers, psychologists, and all kinds of theorists much more to talk about than other more pretentious films.”

The groundhog is Jesus Christ

Since the premiere of Groundhog Day, many fans have tried to determine how many years Murray’s character spends living on February 2. Although the film only shows 38 different days, the information that the protagonist gives about everything he has done, together with the time it would take him to learn to sculpt ice, speak French, or play the piano at the level he demonstrates, recently led journalist Simon Gallagher to place his estimate at 33 years and 350 days.

Others have taken deep dives into its alleged religious subtext. Danny Rubin received letters from monks or Kabbalah researchers who thought the screenwriter was one of them. There are also those who have seen in the transformation of the character a reflection of the path of perfection of Saint Teresa of Ávila, based on the idea of progress from the contemplative life. And then there is the critic and university professor Michael Bronski, who in 2004 argued: “The groundhog is clearly the risen Christ, the ever-hopeful renewal of life in spring. And when I say that the groundhog is Jesus, I say it with great respect.”

Rabbi Niles Goldstein commented on the ending, when the protagonist is allowed to live outside the loop once he has become the best version of himself: “The film tells us, as Judaism does, that the work is not finished until the world has been made perfect.” In Prisioneros del bucle, Alonso and Sánchez go back to other works that have dealt with the theme of time, self-improvement, and the existential trap.

One reference that stands out is the mythical tale of Sisyphus, the character from Greek mythology condemned by the gods to push a large stone up a mountain, which would roll back down just before reaching the top, forcing him to repeat the process for eternity. As the book states, in The Myth of Sisyphus (1942) the philosopher Albert Camus invited us to imagine that the condemned man was happy, because, despite the fact that “the gods thought, with some reason, that there is no punishment more terrible than useless and hopeless work”, Sisyphus still experienced freedom every hour he descended the mountain again.

“The film reflects a model of change that consists of letting oneself accept the repetition,” explains Alonso. “Many people are afraid of repetition because of the feeling of not moving and always doing the same thing over and again, but if you manage to change something in yourself and ride the loop, your perspective changes.”

Sánchez equates the film’s outline with the theory of grief: “According to Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, grief is structured in five phases: denial, anger, negotiation, depression, and acceptance. “They are the steps that the character takes psychologically. Phil is someone with Peter Pan syndrome, who never thinks about anyone, and does whatever he wants, and he progressively acquires a new perspective.”

The evocative influence of Groundhog Day goes further. In 2016, director Cynthia Kao made the short Groundhog Day for a Black Man, a critique of police racism. It tells the story of a Black man who, no matter what he does, is trapped in a loop and always ends up being murdered by a police officer.

It is a premise that was also taken by the Oscar-winning medium-length film Two Distant Strangers (2020). Not to mention other films also devoted to exploring how a decision made on one day can alter an entire existence, a theme that ranges from Edgar Neville’s Spanish classic La vida en un hilo (1945), through Mr. Nobody (2009), until the recent premiere on Netflix last February of the series One Day, an adaptation of the book of the same name by David Nicholls, which shows what it is like every July 15 throughout the life of Emma and Dexter, who meet at their graduation and spend a night together but whose lives take different paths from the morning after.

“I really like stories that take place in a single day, with or without a loop. Also in literature, such as Mrs Dalloway [1925], by Virginia Woolf. It is a way to concentrate an entire life and an entire person on how they live a day,” says Isabel Sánchez. “You can’t see what your life would be like every time you choose to do one thing or another, but art does open those possibilities to you. That cliché phrase ‘live each day as if it were your last’ has a ring of truth because, by chance or by design, any day can change your life.” By the way, the groundhog Punxsutawney Phil has predicted that spring will come early this year.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.