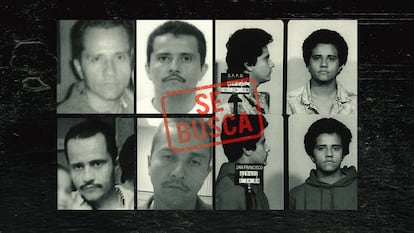

El Mencho, the discreet drug lord in charge of Mexico's most powerful cartel

The boss of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel has never set foot in a Mexican prison, and is defined by the legend of a drug trafficker who rose from the bottom, relying more on violence than on ostentation

At the beginning of the century, police in the Mexican city of Guadalajara raided a house in an affluent neighborhood where they found two AK-47s — Soviet assault rifles, widely used by drug traffickers. But these were special: the AK-47s — known in Mexico as cuerno de cabrito or goat horn — had gold handles. One was engraved with a horse, the other with a rooster — an unmistakable signature of Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera, leader of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), the most powerful cartel in Mexico today, due to the waning power of the Sinaloa Cartel, which is bleeding to death in internal wars.

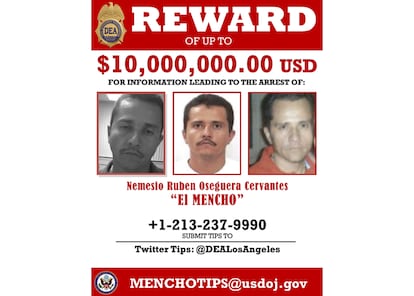

El Mencho has reportedly been killed dozens of times, but he’s still very much alive, continuing his reign in Jalisco. With growing U.S. demands to combat drug lords and curb fentanyl trafficking, many are questioning why he isn’t behind bars, especially since millions of dollars are being offered for any leads that hundreds of people could provide — including members of the police force. One can speculate, but there are no definitive answers.

On February 27, Mexico handed over 29 imprisoned drug lords to the United States, including El Mencho’s brother, Antonio. That same day, his wife, Rosalinda González, was released from prison. El Mencho is said to play his cards with discretion.

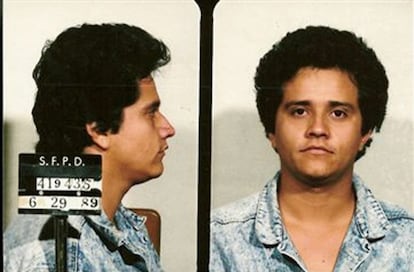

El Mencho — who is known as both Rubén and Nemesio — was born July 17, 1966, in Naranjo de Chila, Michoacán. He grew up amidst poppy fields but soon realized that methamphetamine, which doesn’t require land to thrive, held the key to his rise. He was the son of farmers who immigrated to California, where he first dabbled in drug sales — an act that led to his first appearance before a police camera. This remains the only known photo from his youth, where he is seen with curly hair. Another, more recognizable image shows his serene face with a small mustache. And little else.

El Mencho wasn’t born into drug-trafficking aristocracy, so he climbed through the criminal ranks, starting at the bottom: drug dealer, hitman, chief of hitmen, plaza boss, and eventually regional boss. Those born in less privileged circumstances understand that social advancement often comes through marriage, and Oseguera’s was no exception. He married Rosalinda González Valencia, whose surname opened doors into one of the most powerful drug-trafficking families, the Valencia brothers, also known as the Cuinis.

El Mencho’s criminal career is marked by a mix of betrayals and strategic alliances. Intelligence documents suggest that he played a key role in the arrest of Lobo Valencia in 2009, with El Mencho betraying him at the request of Nacho Coronel from the Sinaloa Cartel. This move elevated him to the head of Los Torcidos, a splinter group of the Valencias, which later evolved into the Jalisco New Generation Cartel.

The CJNG’s structure is paramilitary in nature, characterized by extreme violence, and found a good testing ground in its battle against the Zetas in Veracruz. However, argues Carlos Flores of the Center for Research and Advanced Studies in Social Anthropology, the cartel’s expansion cannot be explained without another critical factor: its ties to political power.

“High-level local political figures were key to the organization’s growth in Veracruz, as were state and federal governments in that state, Michoacán, and Tabasco,” explains Flores, an expert on the collusion between criminals and political power.

This collusion is starkly exposed in a recording where El Mencho viciously reprimands a police commander in Jalisco, berating him for his officers’ behavior and demanding immediate action to rein them in. He spares no insults, calling them a “bunch of bastards” who are pocketing money from his empire.

He is cold and calculating, but discreet. Unlike other drug traffickers, El Mencho hasn’t been caught out by his romantic entanglements, but that doesn’t mean he hasn’t had lovers in his nocturnal circles, says David Saucedo, a drug-crime specialist. Nor has he used his power to commission famous singers to write narcocorridos about his criminal exploits.

“He’s always maintained a low profile, but this strategy of restrain is not only due to his shrewdness but also to what he’s learned from other criminal organizations and the structures that support them —including mercenaries imported from other countries with sophisticated training — not to mention the backing of political and business elites," explains Flores.

If El Mecnho ever set foot in a Mexican prison, there would be a psychological file on him, revealing his eccentricities, perhaps his obsessions, and his tastes. But the kingpin seems to be surrounded by a thick veil of silence, which is only occasionally pierced.

“He manages his security in three concentric circles. First, he’s surrounded by hawks; then, a group of hitmen; and finally, police officers and former military personnel at his service,” explains a source, who asks to remain anonymous.

Flores also suggests that this enigmatic aura surrounding him may be a deliberate strategy “to construct a mythical figure as the head of a cartel that has higher ranks.” It’s rumored that El Mencho suffers from kidney disease, which leads experts to speculate that he may not be as powerful as his own organization.

In the heart of tequila-producing Jalisco, between the towns of El Grullo, Cuautitlán, and Villa Purificación, he has his estates, mansions, and even a private hospital where, they say, he treats his ailments. And who knows, perhaps he also undergoes other cosmetic surgeries, as Flores points out. In the many films and series based on cartel life, fiction often mirrors reality. It’s striking to see his recently detained brother Abraham, who is now an elderly man, and then look at the photo of El Mencho with his small mustache, frozen in time. If he’s ever arrested or killed, the first thing that will shock people will likely be the image of an old, wrinkled man.

El Mencho has ruled Jalisco New Generation Cartel with a firm hand and entrepreneurial audacity. “At the beginning of 2015, investigations into him began, which led authorities to the University of Guadalajara, where he sought out bright young students excelling in law and accounting programs. The goal was to offer them scholarships and recruit them upon graduation,” says the anonymous source. “His network is well-structured, and his activities expanded through offices with lots of phones, just like in the movies.”

But as of 2013, El Mencho still had no criminal record. The first cases were opened by the Jalisco police after a cook who went to cater a party was killed. This incident was followed by a second case involving the death of some fishermen. Rumor has it that El Mencho buys restaurants, assigns one of his own accountants to manage them, and lets them continue running. With his vast cartel network in Mexico, it’s impossible to track where the money for a good meal or medicine might end up. “One of the companies that supplied him with chemical precursors was owned by a Chinese citizen, and it wasn’t just any lab,” notes Flores.

Even in its name, the cartel has always maintained a local focus, earning the favor of Jalisco residents who felt protected by the brand. They’ve consistently marketed themselves as the people’s protectors, peacekeepers in rural areas, benevolent patrons in the field of education, and generous benefactors when the poor need medical care.

And it’s not entirely false. When a family leader was arrested, a notebook containing centuries-old accounting records was seized. “In it, for example, it recorded how, on a certain date, a woman came to ask for help because someone owed her money, or the permission a couple requested to get married. In gratitude, they left 1,000 pesos. The control has been absolute,” the anonymous source says.

These permits and arrangements support the middle and lower levels of the business, while the bosses secure high-profile deals to gain free access to the country’s major ports — Lázaro Cárdenas in Michoacán, Veracruz, and Manzanillo in Colima. “El Mencho has managed to make the right moves and with the right people,” adds the source.

The social power he holds in Jalisco, within his home base, is evident in village festivals, where vendors openly wear aprons with his mustachioed face. That’s when El Mencho digs deep into his pockets, sponsoring rodeos, providing food during the pandemic, distributing toys, or giving away King’s Day roscones. And entertainers, microphones in hand, make sure to make clear who’s footing the bill.

Numerous videos capture these moments, celebrated without restraint; unsurprisingly, the police are also beneficiaries from the same purse. The rooster logo appears on some of these gift boxes. Like his gold-handled AK-47s, roosters have been a weakness for the criminal leader — cockfights, to be more precise, held in bullrings with money and blood at stake. The Lord of the Roosters — that’s what they call him.

Just as El Chapo has his Chapitos and El Mayo has his Mayitos, El Mencho’s succession has been disrupted, with one son captured and extradited to the United States, his brother Antonio arrested, and Abraham imprisoned, facing an uncertain legal path that could lead him out of Mexico through the northern border.

“If he’s captured, this lack of a clear dynastic heir could trigger a civil war within the Jalisco New Generation Cartel,” says David Saucedo. In the meantime, the lord of the roosters quietly nurses his wrinkles away from the public eye, occasionally resurfacing to restore order among unruly police officers or send a shocking message to high-ranking government officials. He’s been killed countless times, but the dead man remains standing.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.