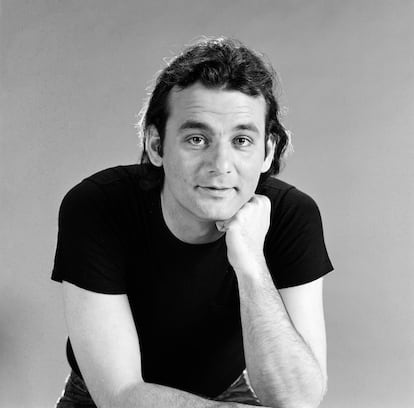

Bill Murray: Half a century of chaos, on and off the set

With his latest film ‘Being Mortal’ on a production pause due to complaints about the actor’s conduct, we reviewed his behavior and bizarre moments in a career spanning nearly 50 years

If you have Bill Murray starring in your film, you might reasonably expect it to succeed. The veteran actor, much-loved for his quirky half-smile, the unexpected depth of his characters, and his talent for improvisation, has helped launch the careers of many indie directors.

You might also assume that, in one way or another, it will not be a straightforward shoot.

The filming of Being Mortal was no exception. It was put on pause last April due to Murray’s “inappropriate behavior,” as a crew member told The New York Times,

Searchlight Pictures (the film’s production company) was placed under full investigation. Speculation was rife that the behavior must have been particularly serious considering that displays of anger, poor relationships with colleagues and generally unpredictable behavior are well-known in the industry to be par for the course in working with Murray.

The speculation was confirmed when Page Six quoted an internal source from the production who said that Murray had been “very hands-on touchy” on set.

The source said Murray had “put an arm around a woman, touched her hair, pulled her ponytail.”

Both that source and another interviewee stressed that, “everybody loves Bill.”

At the same time, they said, “while his conduct is not illegal, some women felt uncomfortable and he crossed a line.”

In an interview with CNBC some days later, Murray said the incident amounted to a failed joke with the woman he was working with.

“I did something I thought was funny and it wasn’t taken that way.”

Murray also said he was “trying to make peace” with the woman who filed the complaint and said the situation has “been quite an education” for him.

“I think it’s a sad dog that can’t learn anymore,” he said. “That’s a really sad puppy that can’t learn anymore. I don’t want to be that sad dog and I have no intention of it.” [sic]

‘The Murricane’

Murray’s reputation for trouble began with his late-1970s stint on Saturday Night Live; his fistfight with Chevy Chase represented a particular highlight.

In 2019, fellow actor Richard Dreyfuss told Page Six that Murray threw an ashtray in his face when they were filming What About Bob?, which was released in 1990.

Murray’s discord with Lucy Liu on the set of Charlie’s Angels (2000) is also well-known. As Liu told Deadline, she spoke up to Murray when he used language that was “inexcusable and unacceptable.”

With friends like Bill Murray, one also does not appear to need enemies. Due to the actor’s sudden, severe mood swings, fellow comedian and frequent co-star Dan Akroyd used to refer to Murray as ‘The Murricane.’ Further, while Ghostbusters (1984) is the most popular comedy of his career, it also marked the end of Murray’s relationship with director Harold Ramis, with whom he had previously collaborated for many years. Murray, who was also going through a divorce at the time, did not speak to Ramis during most of the filming; Ramis has otherwise said that Murray was unable to manage his emotions except through childlike “tantrums.” The two eventually came to blows and did not reconcile until shortly before the latter’s death in 2014.

‘No one is going to believe you’

In his book The Tao of Bill Murray (2016), journalist Gavin Edwards recounts a large number of stories collected from ordinary people describing bizarre encounters with the actor. The many documented events include Murray running up to a stranger while they were waiting at the traffic lights and stealing potatoes from a bag they were carrying; Murray showing up at college parties to do the dishes; Murray delivering pizzas; reaching into people’s pockets to give away money, serving cocktails at a bar, getting pulled over for driving a golf cart early in the morning. Edwards describes a man on a constant personal quest to make the world a stranger place, with the actor seasoning his surprise appearances with the words “No one is going to believe you.”

According to Howard Ramis, the two were once both walking down the street when a fan suddenly approached Murray to tell him how much they liked his work. The actor responded with, “Bastard, I’m going to bite your nose off!” and wrestled with the fan before, indeed, biting his nose in an attempt to carry out the threat to completion.

Edwards also notes that Murray’s ex-wife, costume designer Jennifer Butler, had accused the actor of “aggressive behavior” and won custody of their four children in the divorce proceedings.

Taken together, the stories in The Tao of Bill Murray track with those from the set of Being Mortal, especially in it being difficult to discern when Murray is performing or when he is misbehaving. It likely did not help that the actor has a well-known allergy to following scripts, finds it difficult to arrive on time, and has a fondness for disappearing or simply being impossible to contact. Murray refuses to have an agent and only provides his contact details to a very small circle of trusted people under threat of expulsion if the information is revealed to third parties.

Some colleagues, such as producer Laura Ziskin, have eventually grown tired of working with him – after a dozen collaborations, Ziskin decided to stop after Murray threw her into a lake and broke her sunglasses.

Could there still be life in Being Mortal?

Of his apparent penchant for provocation, Murray told Edwards he is always hoping that someone will jump in, “to wake me up.”

Even his most aggrieved victims have reportedly forgiven Murray – Richard Dreyfuss, Lucy Liu, and Chevy Chase. To be sure, regarding his reputation for being difficult to work with, Murray told The Guardian in 2018 that “I only got that reputation from people I didn’t like working with,” citing Jim Jarmusch, Wes Anderson and Sofia Coppola; three directors who have returned to work with him on multiple occasions.

The films he worked on with those industry luminaries include Broken Flowers (Jarmusch, 2005); Rushmore (Anderson, 1998)’ and Lost in Translation (Coppola, 2003) – all completed and successful productions. It remains to be seen if Being Mortal will be one of them.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.