US scientists who want to move to Europe because of Trump speak out: ‘I’m scared of fascism’

Leading centers in cities like Barcelona and Madrid have been receiving dozens of applications from researchers who fear loss of funds or deportation

In recent weeks, some of Spain’s most cutting-edge research centers have received dozens of applications from scientists based in the U.S. who are seeking to move to Europe to escape Donald Trump’s policies. This newspaper has collected several of their testimonies.

Ray Brown [not his real name] is a 50-year-old cell biologist who has been looking for work in Europe since Trump won the November 5 election. “Everyone around me is talking about leaving,” explains this chief scientist who leads a nine-person team at a prestigious East Coast university. He spoke to EL PAÍS on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals against himself and his family.

“My wife is of Chinese descent,” he explains. “At some point, the Trumpists will go after people of Chinese ethnicity. She was born in the United States and is an American citizen, but I don’t think that protects us anymore,” he explains. “I don’t see it as very likely that they’ll deport me, but I do see it as likely that if they read my name, they’ll cancel my own funding [he has two projects funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)] and that of my entire institution. Those are my fears. I guess what I’m really scared of is fascism,” he reflects.

From NASA to the NIH and the most prestigious universities in the country, there is a fear of speaking out: people are afraid of losing their jobs or having the government take action against the institution to which they belong, as has already happened with Columbia University. The New York institution, whose campus was the site of protests highly critical of the Israeli invasion of Gaza, risked losing some €400 million in federal funding if it didn’t comply with the Trump administration’s demands, which it ended up doing despite having a total budget of around €15 billion with which it could have resisted. Other universities have seen some of their faculty members deported and sustained budget cuts worth tens of millions of dollars due to their transgender inclusion programs.

Brown talks about the reasons that are driving him to seek work in Barcelona, Copenhagen or Oxford, even if it means earning a third of his current salary. “Fascists hate educated people, and they try to destroy the education system in the countries that they control. This is what we’re seeing in Trump’s attacks on universities and in all his policies related to the NIH.”

The NIH is the largest public research organization in the world. Each year, it dedicates approximately €40 billion to funding research groups across the country, and also abroad. It is one of the federal agencies hardest hit by the uncertainty and cuts imposed by Trump. “Funding for indirect costs has dropped from 60% to 15%,” explains Brown. “Universities are already reporting that they are losing money on basic research because they can’t afford the costs of staff and administration. I know of several institutions that won’t be able to survive for long,” he warns. The university where he works is one of many that have completely halted admissions of new students this year; an entire graduating class has been sidelined.

This researcher believes that thousands of high-level scientists will lose their jobs, and many will have no place in the United States, especially those who are not white men. “In five years, there will be no more basic research in the United States. There will be a huge wave of applications to Europe,” he asserts.

A second prestigious scientist who already has a foothold in Europe warns: “Things here are much worse than you Europeans think.” Those who will suffer the most are the youngest researchers, who will have no choice but to emigrate, he warns. Paradoxically, the spokespersons for the first scientific movement that took to the streets to protest against Trump are all young students who are not afraid to give out their names. “It’s a tragedy for the United States and a great opportunity for Europe,” believes this second researcher, who has decades of experience at the top of his field. He doesn’t want to give out his name for fear of the impact on his university, one of the most prestigious ones on the West Coast, and on his family. The “parallels” between the Trump administration and the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 20th century are “astonishing,” he says. “My wife is very active in politics, and she’s also Jewish. The fact that we already had a work visa and could move quickly to Europe was very important to me. In Germany, if you were Jewish and you thought too much about it, it was already too late,” he adds about the Nazi era.

Adam Siepel, a 52-year-old computational biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, is one of the few interviewees who agreed to give out his real identity. He hasn’t yet decided whether he’ll move to Europe, but is exploring options in Barcelona. “We’re afraid of saying anything that could make us a target for retaliation,” he acknowledges. But “at the same time, it’s very important for the world to know what’s happening.” The scientist, who leads a nine-person team, says the cuts announced by Trump will have “devastating” consequences. “When politicians say we’re in a race against China for scientific supremacy, I take them at their word, because I believe in the importance of scientific preeminence for a free and democratic society,” he explains. “That’s why I can’t understand why they’re taking steps that will, in effect, dismantle the world’s greatest scientific infrastructure. And they may be surprised to see how quickly all of this is lost, because science is highly international and mobile. Many scientists already live far from home and have made personal sacrifices to pursue science. If the United States isn’t willing to support them, they’ll go elsewhere. America’s scientific leadership could evaporate surprisingly quickly,” he warns.

All this fear and unease is beginning to reach Europe. The Barcelona Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) has received a dozen applications from U.S.-based scientists in just a few weeks, some from high-level researchers. The Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB) in the same city has received around 10. The National Supercomputing Center has received at least five. These are primarily biomedical scientists in institutions based in Barcelona and Madrid, according to Somma, the alliance of the country’s most cutting-edge research centers.

“We’re being contacted by researchers with funding from the NIH and the Department of Defense, whose funds are frozen,” explains Madrid-based biologist Luis Serrano, director of the CRG. The majority of them are Europeans who have moved to the United States, although there are also a few Americans, including Brown. “The last time something like this happened was after the fall of the Berlin Wall, but at that time most of the top scientists went to the United States,” notes Serrano, who has been a prominent representative of the Spanish scientific community. This scientist believes that Spain should make a budgetary effort to attract this talent. “With about €200 million, we can bring in about 30 top-level scientists. All we need is political will,” he ventures.

The biochemist Francesc Posas, director of the IRB, emphasizes: “We are receiving many more applications than we would expect, from really top people, some of them exceptional in their fields.” This situation is a direct consequence of Trump’s policies, which are causing many laboratories in the country to “implode,” he says. Posas agrees that it is time to take advantage of the momentum with more funding and coordination: “The most cutting-edge centers can attract these scientists with already established programs, but they’ll need to be given additional resources. We need a national strategy.”

Spain is one of the 10 countries that have asked the European Union to take action in this area with a coordinated plan and more funding. The European Commission is already working on this project and wants to double the existing budget for recruiting top-level foreign scientists with an eye to the talent boom emigrating from the United States, as EL PAÍS reported earlier. It’s not just about more money; it’s also about facilitating visas, for example.

Spain is already closing deals with at least eight scientists who are either U.S. citizens or based in the United States to relocate their research. It is doing this thanks to the Atrae (Attract) program, which provides grants of around one million euros per candidate. The program has allowed the return of Spanish researchers, such as the astronomer Noemí Pinilla, and hosted American ones such as the hydrologist Audrey Sawyer. Last year, €30 million were allocated to this program, and in 2025 the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities, headed by Diana Morant, plans to increase the budget. But the program doesn’t always work.

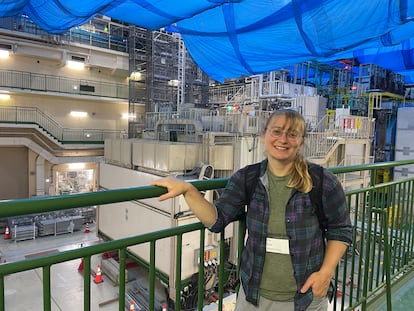

Theoretical physicist Gilly Elor, born 40 years ago in California, received good news in November: she had been awarded an Atrae grant. But four months later, the scientist realizes she will never be able to move to Spain. Elor explains via videoconference that she has been unable to establish a stable line of communication with the grant providers, who tell her there is a problem with her visa. “The only option left for me is to hire a lawyer to take care of the paperwork, and I don’t have the money for this,” she confesses. Her case is particularly poignant, as Elor already lost a Ramón y Cajal contract to settle in Madrid, in this case because the Spanish authorities did not recognize her doctoral degree, issued by the prestigious University of California at Berkeley. Elor’s project is to use particle accelerators to demonstrate an explanation for a small imbalance between elementary particles of matter and antimatter that allowed the Universe to exist. It is a risky investigation that, if confirmed, would likely mean a Nobel Prize. The researcher hopes that by telling her story, the problem can be resolved before the September deadline for coming to Spain. And what does she think of Trump’s policies? “Given that it’s very possible I’ll have to stay in the United States, I won’t comment on that,” she replies.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.