A demolished communist palace and other rubble: How Berlin is managing its GDR buildings and monuments

An exhibition commemorates the demolition of the former parliament building in the German capital in 2008, an example of the persistent erasure of traces of socialism in the city

Every building tells a story. And some of them are uncomfortable with respect to the official story — always cold, coherent and seamless — that every city aspires to convey. This was the case with the Palace of the Republic, which was pulled down in 2008. The demolition of the building, the former seat of the GDR parliament and a house of culture open to the public, brought an official end to the former East German socialist regime, two decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, via the erasure of one of its main emblems in the urban landscape. A symbol as loved as it was hated, destroyed but never forgotten, the building was erected between 1973 and 1976 in the center of Berlin to house the Volkskammer (or People’s Chamber, which wielded very limited powers) as well as a large social and leisure center modeled on the “palaces of culture” in the Iron Curtain countries, such as those in Prague, Warsaw, or Sofia.

The site featured 13 bars and restaurants, a cinema and a theater, an exhibition hall, a post office, a bowling alley and two dance floors. Contaminated by asbestos, it was closed to the public after the reunification of Germany and reduced to a shell. It reopened in 2004, freed of this toxic mineral and of all political baggage, and became a monumental stage for concerts and art exhibitions at a time when Berlin was still an anomaly in the European landscape: a free city, inexpensive and devoid of low-cost tourism. The GDR coat of arms was removed and replaced by an art installation featuring the word Zweifel (or “to doubt”) in giant letters above the main entrance, symbolizing the crossroads at which the city stood regarding its future.

The demise of the building, at once fascinating and ominous, was pronounced in 2006. After a lengthy debate, a committee of 15 experts voted — by eight to seven — to demolish it. Two years later, only rubble remained. Nearby, street vendors sold matryoshkas, military caps and other pro-communist souvenirs, symbols of the so-called Ostalgie (or nostalgia for the East). Some saw in this demolition a definitive emancipation from an authoritarian and illegitimate regime. Others saw it as an official erasure of the GDR and its achievements — social mobility and equality policies are often cited — and a denial of the existence of those who lived within its borders, as part of an operation to file away the darkest chapters of the 20th century in the city.

The controversy over the demolition intensified when, on the site of the Palace of the Republic, a reconstruction of the Berliner Schloss, the official residence of the Hohenzollern dynasty between 1443 and 1918, was erected. Damaged during the Second World War, it was destroyed in 1951 by the GDR, which also wanted to impose its own narrative on the Berlin landscape. An example of late Baroque, this pastiche of the old palace was rebuilt in a modernized version — part of the new facade is neo-rationalist — with funding from German industrialists nostalgic for the architecture of yesteryear. From this emerged a new cultural center, inaugurated in 2020 as the Humboldt Forum, which exhibits the collections of the Ethnological Museum and the Asian Art Museum. A project that may seem ill-advised in an era debating decolonization and the restitution of works: this showcase of imperial spoils stands on the very spot where Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered acts of genocide in his colonies. Even before its inauguration, the Humboldt Forum had had to announce the return of the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, leaving the room intended to exhibit them standing empty.

Even so, this outlandish project, installed in a space with the aura of a shopping mall, has against all odds become a suggestive place. The key has been to stop hiding its incongruous history and to assume it with transparency: when all is said and done, it is a trait it shares with the rest of the city. Its most recent gesture: a tribute to the Brutalist building that had to disappear to make room for this shoddy imperial palace. A new exhibition, on view at the Humboldt Forum until February 2025, traces the history of the Palace of the Republic through 300 objects, from the crockery in the restaurants to the works of art that decorated its grounds, displayed with clinical detachment and not too much nostalgia. It also includes 50 interviews with GDR citizens who managed the building, worked in it, or visited it.

At one time the museum’s own director, Hartmut Dorgerloh, who grew up in the GDR, was against the destruction of the Palace of the Republic. Today, he is in favor of turning it into a place of remembrance. “This episode shows that you can demolish a building, but you can’t erase people’s memories,” he says from his office in the heart of Berlin. “We can interpret its demolition as a sign of disdain for the lives of GDR citizens, but it was not a triumphal symbol of the victory of the West over the East. The will was to heal the wounds of the past. At the time, no one was talking about sustainability or urban memory. Sensitivity to these issues has evolved. Today, such a thing would not happen again.”

This episode shows that you can demolish a building, but you can’t erase people’s memories.Hartmut Dorgerloh, director of the Humboldt Forum

The demolition of the Palace of the Republic is not an exception, but the most famous case of the gradual erasure of the GDR’s memory from the urban space since German reunification. A few meters from the Humboldt Forum, the former GDR Ministry of Construction, was partially destroyed a decade ago. Today it is a steel and concrete skeleton waiting to be put to new uses. “The building offers considerable potential for the development of an urban mix of apartments, stores, restaurants and offices,” reads a sign on the first floor.

Of course, this transformation is also due to the capitalist awakening of the former socialist cities, where private property was almost non-existent. “There is little interest in investing in the renovation of GDR buildings when economically it is more viable to tear them down and start over,” says Kirsty Bell, author of The Undercurrents, a recent essay on the German capital’s unintelligible urban landscape. “Although the same logic drives many urban planning decisions in West Berlin,” she adds.

Examples abound, from the Ahornblatt building, a sophisticated emblem of German brutalism next to Alexanderplatz, which was demolished in 2000 — it contained a self-service restaurant with almost 1,000 seats that GDR officials used to frequent — to the recent demolition in February of this year of the Generalshotel at Schönefeld airport, renamed Berlin-Brandenburg, which used to host the leaders of the Soviet Union. The half-ruined House of Statistics in the center of Berlin houses artists and non-profit organizations while waiting to be converted into an office block.

Tacheles was one of the most famous squats in East Berlin: after the fall of the Wall, an artists’ collective moved in and set up studios for painters, a cinema, a nightclub and a public garden. They were evicted in 2012. Since 2023, the site has housed the Berlin branch of Fotografiska, a prestigious Swedish photography museum with an upscale restaurant on its top floor, although the anarchic graffiti on its staircase, which made it famous in its day, remains in place. The alliance of poorly disguised turbo-capitalism and the anti-liberal aesthetics of yesteryear is a mixture as absurd as it is perfect to define the infinite contradictions of modern-day Berlin.

Meanwhile small, dusty museums survive in various parts of East Berlin, such as the historical center of the Kulturbrauerei, in the eastern district of Prenzlauer Berg, or the Stasi Museum, in Lichtenberg, an enclave impossible to gentrify where working class survivors coexist with Turkish immigrants in a landscape drawn by endless rows of dreary socialist buildings, the so-called Plattenbauten, converted into unsuspected objects of architectural worship.

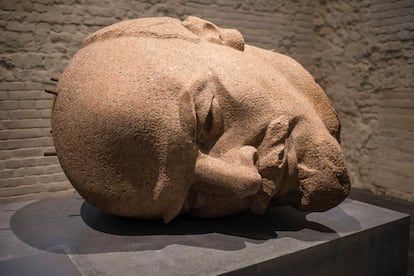

The Stasi Museum is located in the former headquarters of the GDR intelligence agency, in charge of the surveillance of citizens, repression of political dissidence and protection of communism. At the other end of the city, the Spandau Citadel has become a warehouse of uncomfortable statues, the kind that no one wants to see in public spaces, defined as “toxic objects of memory” by its director, Urte Evert. Among these is the head of a 19-meter statue of Lenin, which was dismembered and buried in the Müggelheim forest, southeast of the city, and has been on public display since 2016.

“The acrimonious struggle over the Palace of the Republic is an example of a broader struggle between erasure and memory. The symbols of the GDR were only part of history for a minority of the population: the East Germans. Western politicians, who were in the majority, did nothing to save something they never felt was theirs,” concludes essayist Katja Hoyer, author of Diesseits der Mauer (On This Side of The Wall), a best-selling book describing daily life in the GDR, accused by its detractors of advocating ‘pastel socialism,’ as Der Tagesspiegel said, or even ‘a comfortable dictatorship,’ according to the Süddeutsche Zeitung.

In fact, Hoyer seems to be interested in reinterpreting the official account of reunification, also contested by novelists who grew up in the GDR, such as Jenny Erpenbeck or Clemens Meyer. It is a political, aesthetic and, above all, cyclical question. “Sometimes it takes time, one or two generations, to understand the quality of some types of architecture,” notes Dorgerloh, who believes that we have already reached that moment of re-evaluation. While the endless Karl-Marx-Allee, the grand avenue of East Berlin, is now regarded with unprecedented prestige for its urbanistic features, a group of activists in 2021 tabled a most surreal request, which only makes sense in a city like Berlin. The collective demands the immediate demolition of the Humboldt Forum and the rebuilding of the Palace of the Republic by 2050. And then it’s back to square one.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.