Agent Sonya: a wife, mother and perhaps the best spy of all time

In his new book, historian Ben Macintyre explores the life of a woman who became a Red Army colonel, a successful writer and a top secret operative while raising three children

Ursula Kuczynski, alias Ruth Werner, alias Agent Sonya, was a Red Army officer and an expert in radio communication, a saboteur, a first-rate spy and a successful writer. She achieved all of these things while raising a family, which was both a perfect alibi and a fateful trap. If her story is not well-known, it is because until now it has not been written about.

Historian Ben Macintyre, the author of several books on the shadowy world of espionage and who has recently published the Spanish-language edition of his 2020 book Agent Sonya: Moscow’s Most Daring Wartime Spy, explains over the phone from the UK: “Today people talk a lot about how to balance work and family life, but in Ursula Kuczynski’s case it took place on a completely different level. Her work was lethal. If she failed, she would die and her family as well. She had a remarkable capacity for compartmentalizing, something that all great spies are able to do, but she admitted that if it had come down to a conflict between her family and the revolution, she would have chosen the revolution. In many ways she was a fanatical communist. That she was a woman was her best disguise, but it is also the reason we didn’t know anything about her.”

The second of six children in a well-to-do Jewish family, Kuczynski was born in Berlin in 1907 and grew up in a Germany mired in the ideological struggle between the far right and the left. At the age of 19 she joined the German Communist Party and allied herself to a cause she would never abandon. In 1930 she fled the growing reach of the Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, and moved to a convulsive Shanghai with her first husband, the architect Rudi Hamburger.

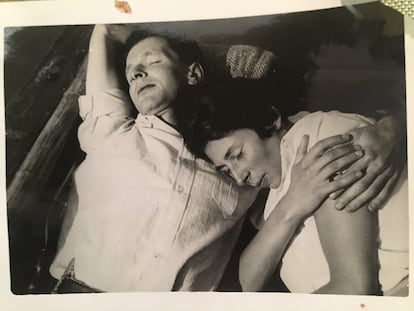

There Kuczynski met the spy Richard Sorge, embarking on a brief and intense romance and thereafter always carrying a photo of him with her. It was Sorge who gave Kuczynski her nom de guerre, and got her hooked on a clandestine existence of secrets and loyalties. When Sorge was arrested and executed in Japan at the end of one of the most impressive careers in the history of espionage, he never revealed Ursula’s identity. “All spies are convinced they are working for the most unimpeachable ideals, but it is always much more complicated than that. Espionage is both complex and addictive. Secrets are a very potent drug. Once you become a part of this elite it is very difficult to leave it and she was, furthermore, very ambitious. And of course, if you are working for the Soviets there is a practical element to consider: if you try to leave, they’ll probably kill you,” says Macintyre.

Macintyre, born in Oxford in 1963, is one of the most accomplished narrators of the history of espionage but he admits he had never encountered a case like Kuczynski’s previously. “What sets her apart from any other spy I have come across is that she was a professional,” the author explains. “She chose to work in the world of intelligence as a career, as a vocation. The majority of female spies worked for men on subsidiary missions or as informants. There are really very few who rose to be officers and I don’t know of any who were colonels in the Red Army. And nobody ever made it as far as she did in any intelligence service.”

Extremely adept at covering her tracks, during her lengthy career Agent Sonya evaded capture by the Gestapo, the Chinese secret police and Japan’s Kenpeitai and, during her time as a refugee in England in World War II, she also flew under the radar of British counter-intelligence. “The MI5 reports are hugely entertaining,” says Macintyre with a chuckle. “She was systematically underestimated by men and they failed time and time again to identify this woman who was looking after her children, wearing an apron and baking a birthday cake when they turned up to interrogate her, as someone who potentially could be the perfect spy. And she exploited that advantage as much as she could.” In MI5′s defense, despite the “incompetence and chauvinism” of many of its members, the agent Milicent Bagot insisted on several occasions that Kuczynski and the rest of her family who were living with her (above all her father and brother) were Soviet spies. She was correct, but she was a woman and so nobody paid her suspicions any heed.

However, Kuczynski had more formidable enemies: her own employers. Agent Sonya survived the Stalinist terror that swept away most of the structure of Soviet espionage, including many of her colleagues and friends, a danse macabre of denunciation and death that resulted in the arrest of 1.5 million people and the execution of more than 680,000 over two years. Macintyre believes there are two reasons for this: her enormous capacity for inspiring loyalty – “an essential part of the work of a spy, gaining the trust of others and convincing them that their future depends on their personal loyalty to you” – and a most extraordinary run of luck: “She was spared when so many others perished. For a variety of reasons, she could very easily have ended up with a bullet in the back of the neck in the basements of Lubyanka.”

Among Agent Sonya’s numerous achievements in Switzerland, China, Japanese-occupied Manchuria and Britain, one stands above all the rest: her handling of Klaus Fuchs, a German nuclear physicist, member of the Manhattan Project and Soviet spy who also worked on British research into the construction of an atomic bomb. In line with her commitment to the double life she led, Kuczynski gave birth to her third child in 1943, days after arranging for the final instalment of a 570-page document containing key information from the British atomic project to be delivered to Moscow from her home in the English countryside. It was a triumph of espionage that advanced Soviet nuclear ambitions by several years, leading to equilibrium between the WWII allied powers and paving the way for the Cold War.

In 1950, after Fuchs confessed to his wartime activities as a spy, MI5 admitted Kuczynski ran a network of agents on British soil but attempted to play down the magnitude of the security breach. However, British intelligence still refuses to acknowledge that “this woman so busy with domestic tasks” who loved to go on long bicycle rides (during which she would meet with her informants) was the master spy she is now known to have been. In 1949, Kuczynski had returned to her native Germany and the nascent GDR, which she viewed as a communist paradise, to settle with her second husband, Len, and her three children. Leaving behind her life as a spy, from 1956 onward she found fame as a writer under the name Ruth Werner. In 1969 she was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. She harbored doubts and fears and lived a life of pain and loss, committed to a single cause, but she never regretted what she had done.

“Ursula’s children idolized her, but they didn’t fully trust her and they wondered how well they knew her,” writes Macintyre in his book. Peter, Michael and Nina were the fruit of three separate relationships and always felt loved and cared for, even if they were unaware of their mother’s work for a period of time during their lives: much like the rest of the world, who only now are becoming aware of the story of perhaps the greatest spy in history.

A career unveiling the lives of famous spies

During his long career, Ben Macintyre has told the stories of the lives of some of the most famous figures in espionage like Kim Philby and Oleg Gordievski in books that combine meticulous research with narrative fiction techniques. Part of the strength of his books comes from the treatment he gives to the personalities whose stories he tells, including the secondary actors. Among these, MI5 agent Roger Hollis stands out in his latest book. Hollis is still under suspicion of having been a Soviet spy, with some writers attributing his incompetence in failing to unmask Kuczynski or the members of the Cambridge Five spy ring, in which Philby was a key player, to ulterior motives. “I don’t believe that. I’d love it to be the case, but I find it difficult to imagine that Putin would have passed up the opportunity to boast about something like that,” Macintyre says with a laugh.

English version by Rob Train.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.