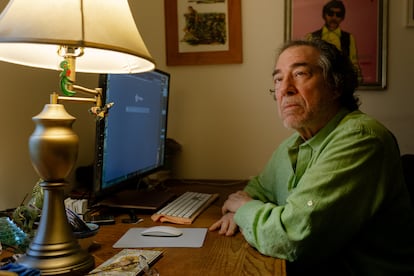

Dagoberto Gilb, writer and essayist: ‘To Americans, Chicano culture doesn’t exist’

The Mexican-American author, known for his short stories and essays portraying the working class to which he belonged, calls, without much hope, for Chicano culture to be fully present within the US cultural imagination

A full 75 years after being born in the United States, Dagoberto Gilb is still seen as an exotic man, while in Mexico, he’s just another gringo. The latter doesn’t bother him: he understands where it comes from, as he barely speaks Spanish and has lived practically his entire life north of the border. The former, on the other hand, gets on his nerves, but he accepts it with the resignation of someone who knows in advance that they’re on the losing side. The Mexican-American writer — MexAm or Chicano, he would say — is known for his stories and essays about the working class to which he has belonged his entire life, and last year he published two new books, one fiction and one non-fiction, which once again portray the everyday life without stereotypes of a community that, though comprising the majority of the population on the U.S. southern border, continues to be looked down upon by the hegemonic culture.

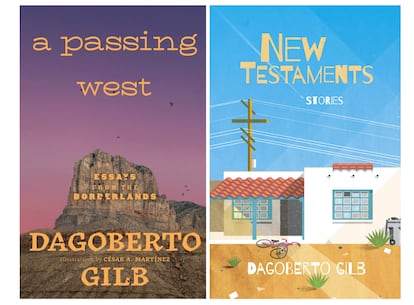

Gilb, whose works have appeared in magazines such as The New Yorker, Harper’s, and Best American Essays, does not conceive of his work as a political exercise. Indeed, nothing explicitly political is evident in his lines, yet his stories, brought together in the collection New Testaments, published by City Lights Press, and the essays in A Passing West: Notes from the Borderlands, edited by the University of New Mexico and filled with social critique, are difficult to interpret in any other key. Especially in the current context. Together — despite not actually being a pair — the two books converse with and complement each other. The essays are like a black-and-white delineated drawing, while the fictional stories bring color to the picture.

Like someone scoring a tree trunk with a knife to leave a mark of their passage, Dagoberto Gilb’s work marks a presence on behalf of Chicanos, whose complex identity he reflects with such familiarity that he takes it for granted. It’s not a question of explaining anything. His is a visceral response, a bang on the table: “We don’t matter. For them, Chicano culture doesn’t exist. We are a collection of tropes, stereotypes, and clichés. We don’t think about ourselves following their rules, because their rules have us all as immigrants,” he says via video call from Austin, Texas, where he lives part-time, having also resided in Mexico City for years on a kind of semi-permanent Chicano pilgrimage.

His banner is the American Southwest, a territory of Indian and cowboy legends, but, in his reading of it, of a dominant white, Anglo culture. “When people think of America’s spectacular Southwest, when they see the shapes of those states in their mind, it is never about the Brown people who are there. The raw, desolate beauty of the landscape, yes. The hip ‘Spanish adobe’ architecture in it, yes. The tasty food that abides, definitely yes. But the people? Americans know of them like they do a few words of Spanish in Cancún. The people who have lived there, who live there now and still? They are absent, purged, not one pretty shade in that mental map. Legacy, sure, that’s very cool. A unique, thriving living community and culture? Cowboys and Indians, that’s who’s there and been there,” he writes in the essay We Have Been Here All Along, one of two unpublished texts in the collection. In it, he expresses anger that “the voice of the Southwest” is that of Cormac McCarthy, a white writer born in Rhode Island and raised in Tennessee, and that the history of the region, which expands generously from California to Texas and dates back to before the United States or Mexico as we know them today even existed, is reduced to “a tourist Chinatown at best.”

The 25 stories in A Passing West, most of which were published in various magazines in the last decade, examine borderlands and their societies with a clarity only achieved by those who are a part of them. Many of the texts contain autobiographical passages and anecdotes that reveal the author’s natural habitat.

In the stories of New Testaments, that ecosystem is the same, and although Dagobert Gilb isn’t the name of the characters, more than one has parts of him within them. The writer also admits that while he has “mixed feelings” about Jack Kerouac, he admires the fact that “he lived a life”; the implication is that to write credibly about something, you have to have experience. Among his recent stories, three are about elderly men, all lonely and frail, two of them with disabilities caused by car accidents. Gilb, who is still living with the ravages of a stroke, knows a lot about that.

Born in Los Angeles in the years after World War II, the son of a Mexican mother and a white father of German descent who somehow spoke Spanish, Gilb says he had a difficult upbringing, though he didn’t know it at the time. His parents separated, and he doesn’t have many memories of his father until he started working at the industrial laundry, where he was the manager for decades. Meanwhile, his mother, a very beautiful woman, went from boyfriend to boyfriend. Young Gilb never bothered to get to know them, and he didn’t spend much time at home either; he’d go away for a few days, a few weeks, and then come back as if nothing had happened. “Looking back, I wish I could have talked to them. Asked them about their lives,” he says.

His life changed when he graduated in the turbulent year of 1968, when the Vietnam War seemed like the inevitable future for working-class youth like himself. After hearing about his friends’ experiences, he decided he would do everything he could to avoid the draft, so he enrolled in community college. “My life was completely turned upside down. I’d never read a book. I didn’t know anything, and I didn’t know I didn’t know anything. Every class was like a new girl I always wanted to be with,” he recalls. Eventually, he majored in religion and began writing.

But reality hit him. For years, no one would buy his stories; there was no interest in the stories of working people, so he rolled up his sleeves every day and worked as a construction worker to feed his two children — “they always needed shoes” — and his wife. Still, for 16 years, when physical labor on construction sites alongside his union colleagues was what put food on the table, he wrote. “I wrote as an object. I wrote about them [the workers] as a member. It’s all I know. Ray Carver was writing about the working class at the same time, and I remember reading his stories and thinking: that isn’t a story about work. Workers are not morose. Dudes that are at jobs. They maybe have too much fun. They’re too little wild. They’re not really moping around...”

When he was about to give up, in the early 1990s, he sent a selection of about 25 stories to the University of New Mexico and managed to publish the book The Magic of Blood, which won him the PEN/Hemingway Award for debut writers. From then on, life was never the same. “I couldn’t have gotten more attention. I didn’t sell as many as some others, but I did well. I got work in prestigious creative writing courses. And I’d never even taken an English class.” In the following decades, he published a handful more books, and his byline appeared frequently in some of the country’s most prestigious magazines.

But making ends meet never stopped being a challenge. “I didn’t know this business was so ridiculous,” he says. “It’s for rich kids. And I’m not a rich kid. It’s really fucking hard. How do people live on that money? You can’t pay rent as a writer,” he says angrily. And then, in 2009, a stroke left him with a disability that he has slowly learned to master, but which severely impacted his productivity.

Until last year, when he published two books in a row, and for a moment it seemed like a new beginning. But reality struck again: Dagoberto Gilb’s name is no longer as well-known, promotion has been difficult, and sales have been limited. The world — which at the time of his latest books was focused on a surreal presidential campaign with attacks and candidate changes just months before the election — has moved on and left him behind, Gilb admits.

His writing continues to give voice to a rarely explored experience of life in a natural and relatable way. That, he says with conviction, doesn’t change. But when he looks at the world convulsing around him, he admits he’s lost. “I wish I could, I wish I could say something. I can’t tell the difference between up, down, left, and right. I don’t know. We’re going fast, we’re going slow. I don’t know what’s going on. I’m really very confused,” before imagining a massive mobilization of people, like in the days of the civil rights protests.

For a moment he gets excited, then the eyes that had lit up very fleetingly go out and betray his little faith in formal politics. Then comes his analysis. “What I think happened to the Democratic Party is that they don’t know who they are supposed to be talking to. They don’t know what it’s like to work for an hourly wage. None of them have had a job where they can get fired by an asshole boss like Trump. They’ve never had that job.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.