A recipe for resistance: Indigenous peoples politicize their struggles from the kitchen

A book that compiles the recovery of ancestral recipes from the Americas, from Canada to the Amazon, maps strategies in the face of climate change and agribusiness

To cook chipa de pescado (a baked fish dish) with roasted yucca, the Asháninka Indigenous community of Peru must first gather bijao leaves to wrap the scaled fish in a leaf that will also serve as a plate. This community must also have fished for boquichico (black prochilodus) or chupadora (suckermouth catfish), in the Pichis River basin; quite a challenge since the widespread use of explosives and nets that barely allow the fish to grow. Similarly, to make toasted wheat soup, typical of the Quechua people in Bolivia, garlic, cumin, and red chili peppers, which they carefully harvest themselves, must be ground on a stone mortar. The story behind these ancestral recipes begins long before the fire is lit. It involves the selection of seeds, the methods of cultivation and fishing, how and with whom food is eaten, and how it is served. In a world where Western diets are increasingly limited to fewer food groups, keeping this diverse and colorful gastronomy alive is an act of resistance.

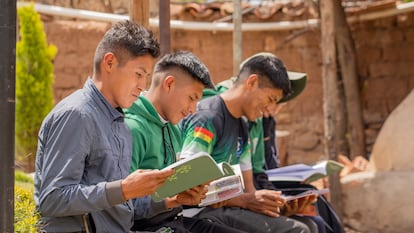

A year ago, a group of 10 Indigenous communities from across the continent (Asháninka, Aymara, Kayambi, Cree, Inuit, Nahuatl, Maya Q’eqchi’, Métis, Misak, and Wolastoquey) gathered in the cloud forests of Yunguilla, Ecuador. People from Canada, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia spent several days discussing the transformation of Indigenous food systems, the similarities in their traditional dishes, the need to incorporate technology into their daily processes, and the importance of seed sovereignty. The conversations yielded enough material for a book. So they published it. The result of these long discussions, and with the support of Rimisp, the Latin American Center for Rural Development, was the publication in late 2025 of Cultura alimentaria indígena: Territorio, tradición y transformación (Indigenous food culture: Territory, tradition, and transformation), a work that connects distant peoples with similar struggles.

Rodrigo Yáñez, director of Rimisp and editor of the book, recalls these exchanges, how they began as a challenge due to the language barrier itself and ended with a shared agenda with more points in common than differences. “The words that were repeated most often were sovereignty and resistance. These are two demands that go far beyond the food served at the meal,” explains the PhD in sociology. It has to do, he says in an interview with EL PAÍS, with land ownership, the right to water, the incursion of ultra-processed foods, the effects of climate change on crops… “Indigenous peoples know that they are part of global societies, with very similar challenges. Their way of seeking political strategies through food can also provide global solutions.”

Traditional dishes are not only the result of the alchemy of what women harvest in their gardens, they also accompany community milestones. Just as mole is synonymous with celebration for the Nahua people of Mexico, kaq ik is cooked when the Q’eqchi’ Maya of Guatemala are about to plant corn, and the Misak often eat sango from the same pot after a long day. “The original dishes are the most authentic, those that have been consumed for hundreds of years in my community, because they have not only nutritional value, but also spiritual value. They also possess a wealth of biodiversity, since they come from crops that are native to us,” explains Kelly Ulcuango, a Kayambi Kichwa woman from Ecuador, in the book.

Everyone involved in the book agrees on one thing: revolution also happens in the kitchen. There’s something deeply political behind what we consume, both in the Amazon and in any Latin American capital. That’s why these 73 pages capture the political perspective of these communities, their stance on access to food, food sovereignty, an analysis of the transformations of food systems over time, interviews, and detailed notes on each recipe, written by those who still remember their grandmothers stirring the pot or anticipating the menu by its aroma.

Another concern these communities face is how to promote their crops without it backfiring. There are many examples of ancestral American foods that become popular in the West — even in haute cuisine — and end up eroding community ties, creating monocultures, or altering community diets. Examples include açaí in Brazil, quinoa in Bolivia, Colombian coffee, ant eggs in Mexico, and cacao in Central America.

Therefore, Yáñez tries to put the concept of food sovereignty at the center. “Indigenous peoples are very aware that they are part of a global society, but sovereignty implies having some decision-making power over what is produced, consumed, and how food is accessed,” he explains. “When cases like these arise, I think about how to ensure that what is produced doesn’t end up being uprooted from the territory simply because it generates a good economic return.” More than anything, he explains, because if these exports are not curbed, the loss of food sovereignty ultimately translates into food insecurity.

But in this book, there is little room for catastrophism and alarmism. Its pages brightly illuminate the space for change and transformation toward more conscious models. This research champions food as a collective and territorial practice capable of sparking a revolution. “The richness of these territories lies in their defense of the right to difference,” the sociologist concludes. “They speak of resistance because they know that diverse diets that preserve traditions are also contested. Indigenous peoples are also subjected to the homogenization of diets,” he laments. However, the expert clings to the pride with which each Indigenous person he visits in their home shows their garden plot, how much the chard, chili peppers, or cilantro have grown. “That pride in diversity is what they can contribute to the West.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.