Maduro’s downfall puts China’s relationship with Venezuela to the test

Beijing and Caracas strengthened their strategic partnership in 2023, but this does not entail security commitments

For nearly two decades, China has been more than just a trading partner for Venezuela: a key political backer, a financial lifeline during the worst years of sanctions, and an ally willing to defy the isolation imposed by the United States. But the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces early Saturday has tested the strength of the Beijing‑Caracas strategic partnership like never before. And although the Asian giant has criticized Washington’s “hegemonic acts” and demanded the immediate release of Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, there is broad consensus among analysts that its response will remain largely rhetorical.

“China is deeply shocked and strongly condemns the reckless use of force by the United States against a sovereign state and the actions directed against the president of another country,” the Chinese Foreign Ministry said in a brief statement released about eight hours after explosions began in various parts of Venezuela, including the capital. On Sunday, the Chinese Foreign Ministry called on the U.S. “to ensure the personal safety of President Maduro and his wife, release them at once, stop toppling the government of Venezuela, and resolve issues through dialogue and negotiation.”

In both statements, Beijing denounced what it considers a “serious transgression” of international law, a “violation of Venezuelan sovereignty,” and a “threat to the peace and security of Latin America and the Caribbean.” “We call on the U.S. to abide by international law and the purposes and principles of the U.N. Charter, and stop violating other countries’ sovereignty and security,” a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said on Saturday.

The tone aligns with Beijing’s line over the past few months, during which it expressed opposition to the naval and air deployments Washington has maintained in the Caribbean since August and reaffirmed support for the Maduro regime as U.S. pressure mounted. In mid‑December, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi assured his Venezuelan counterpart, Yván Gil, over the phone that his country opposed “all forms of intimidation” and supported “the defense of Venezuela’s sovereignty and national dignity.” However, Beijing avoided backing that rhetoric with concrete actions.

That caution reflects several factors. Venezuela does not occupy a central place in China’s global strategic priorities, which are focused on the Asia-Pacific region (with particular emphasis on Taiwan), trade ties with Europe, and structural competition with the United States — a framework that helps explain why the Chinese government did not immediately respond to Maduro’s capture.

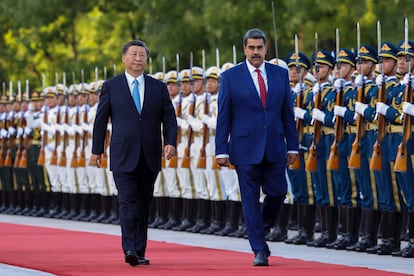

Beijing doesn’t have much room to maneuver. In 2023, during Maduro’s state visit to China, the China-Venezuelan relationship was elevated to the level of an “all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership,” but this flowery political recognition doesn’t imply any security commitments. Moreover, experts point out that, for China, Venezuela is a useful partner on a rhetorical and symbolic level, rather than an ally to whom it would be willing to offer military support in a scenario of direct confrontation with the United States.

“China’s position when some of its partners face a crisis is limited,” argues Inés Arco, a researcher at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB) specializing in East Asia, in an exchange of messages. “When the United States bombed Iran, a closer ally of China than Venezuela and in a similar situation of energy importance and international sanctions, Beijing offered no further support beyond rhetoric,” says Arco. “Ultimately, China presents itself as an economic partner, not a security partner.”

Such limits are not new. In recent years, Beijing has pragmatically recalibrated its relationship with Caracas, following a period of high financial exposure between 2007 and 2015, during which it provided Venezuela with oil-backed loans totaling more than $60 billion (equivalent to 16% of its GDP), according to data from the Inter-American Dialogue and Boston University. After the collapse of oil production, the Venezuelan economic downturn from 2014 onward, and the tightening of sanctions, China drastically cut financing and direct investment. Since then, Venezuela’s real economic weight for China has diminished compared with other regional partners such as Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Mexico.

In this context, the relationship has increasingly centered on the energy sector. China, the world’s largest crude importer, has been the main destination for Venezuelan oil exports since 2019, as U.S. sanctions closed off other markets. Although Venezuelan crude accounts for only about 4% of China’s total imports, it has been a lifeline for Caracas: between 2023 and 2025, China absorbed between 55% and 80% of Venezuelan exports in many months, according to calculations cited by Reuters. These sales have been essential for the Chavista regime to maintain a minimal flow of foreign-currency revenue while access to Western markets was restricted.

Although economic ties have been gradually limited, Venezuela has continued to serve China as a useful element in its narrative. Chinese foreign policy, especially under President Xi Jinping, is organized around the defense of sovereignty, rejection of unilateral sanctions, and opposition to external interference. These positions are consistently reiterated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, while carefully avoiding stances that could lead to an open confrontation with Washington. Within this framework, diplomatic support for Caracas during recent months of tension has allowed Beijing to reinforce its narrative against U.S. unilateralism and project an image of strong support for the Global South, at a time when U.S. President Donald Trump was repeatedly undermining the multilateral order.

A few hours before his capture, Maduro praised the “unbreakable bond” between Venezuela and China and expressed his gratitude to Xi “for his fraternal support, like an older brother.” He did so during a meeting in Caracas with a Chinese delegation led by Qiu Xiaqi, the special envoy for Latin America and the Caribbean — a meeting that neither the Chinese government nor state media have publicly reported.

At the end of November, Xi described the two countries as “close friends, dear brothers, and good partners” and reiterated his categorical rejection of “interference by external forces in Venezuela’s internal affairs.” The Chinese leader was also one of the few world leaders to congratulate Maduro on his victory in the 2024 presidential elections, which were questioned by much of the international community and widely condemned as fraudulent.

The Venezuelan crisis also unfolds amid growing rivalry between China and the United States for influence in Latin America. In early December, Washington published a new National Security Strategy that redefines the region as a “core national interest” and presents an updated version of the Monroe Doctrine, aimed at restoring U.S. primacy in the Western Hemisphere and protecting key strategic corridors.

Although it does not explicitly mention China, the strategy prioritizes preventing “non-hemispheric competitors” from deploying forces or controlling strategic assets and warns of the need to identify and counter “hostile foreign influences,” a framework analysts interpret as a direct reference to China’s growing presence in the region. Days later, Beijing released its third Policy Document for Latin America and the Caribbean (the first in nine years), portraying Latin America as an essential force in the transition to a multipolar order and emphasizing that its relationships “neither target nor exclude third parties, nor are they subordinated to any country.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.