John Belushi: The overdose that marked an end and a beginning in Hollywood

The ‘Saturday Night Live’ star was the biggest comedian of the 1970s. His death in 1982 left the industry in shock and led to a reassessment of the drug culture in the film industry

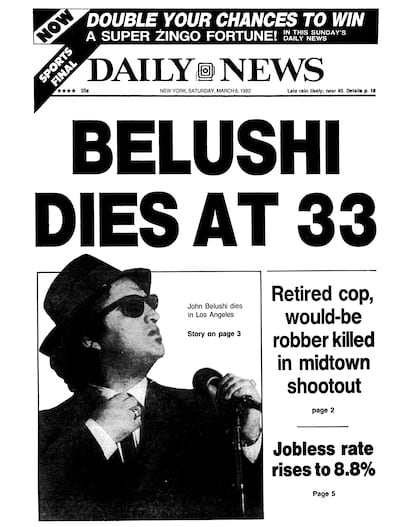

In Hollywood, the saying goes that the 1970s ended on March 5, 1982, the day that John Belushi died from an overdose of cocaine and heroin. “The game was up,” Taxi Driver director Paul Schrader would recall. “Some people stopped straight away; the feeling was that the rules had changed.” Bob Woodward’s 1984 biography of the comedian and actor, Wired: The Short Life and Fast Times of John Belushi, has recently been reissued in Spain, in which the journalist who uncovered the Watergate scandal paints a portrait not only of a man who was incapable of controlling his demons and impulses, but of a culture, that of Hollywood in the 1970s, that tolerated, facilitated and celebrated the rampant consumption of drugs.

It is hard to overstate Belushi’s impact on American culture, but it is also difficult to understand outside of his time. During an era of mistrust of the institutions and a crisis of values, after Nixon’s fall and the incapacity of Jimmy Carter, the US found a vehicle for its catharsis in Belushi. His humor was unpredictable, anarchic, uncomfortable, anti-system, surrealist and impulsive. “He adapted the counterculture to comedy,” says Toni García Ramón, author of the Spanish reissue of the prolog to Wired. “He was one of the first to pull jokes out of his sleeve, to improvise everything. He came from that dark, dirty, punk New York that Giuliani would later take on. Belushi was pure counterculture, he never bowed to anyone. He would walk into any sketch and blow it up. His greatest discovery was bringing street humor to the television, making the public at large laugh at the rough jokes people would tell in Hell’s Kitchen bars full of transvestites, punks and hookers.”

Saturday Night Live (SNL) was the first show created by and for that generation who were born at the same time as television. Belushi used the platform to do things nobody thought could be done on television: he shoved cigars up his nose, smashed beer cans on his forehead, filled his mouth with food and spat it out. Through comedy, he dissected human behavior and parodied a masculinity that, in the middle of a second wave of feminism, had become childish, primitive and explosive. His style of humor was imitated so many times that it swiftly lost its impact, but in 1975 it made Belushi, 26, a national idol. “He represented all of the messy bedrooms in America,” said Steven Spielberg, who directed Belushi in 1941.

Belushi developed his ability to dissect American culture during adolescence. “He was a great observer,” says García Ramón. “He came from a family of immigrants that never integrated and knew little about the United States. He spent the afternoons at his classmates’ houses. He had to completely reinvent himself. And that’s one of the things that made him stand out as a comedian. He was the only person who could do it because he had invented it.”

In 1978, Belushi had the most-watched show on television, a number one record with the Blues Brothers, the duo he formed with Dan Aykroyd, to warm up the Saturday Night Live audience before filming, and the highest-grossing comedy movie in history at the time, National Lampoon’s Animal House.

“John would literally hail police cars like taxis. The cops would say, ‘Hey, Belushi!’ Then we’d fall into the backseat and the cops would drive us home,” writer and producer Mitch Glazer told Vanity Fair. For the first time in history, young people were in charge. The US had become one big university campus and Belushi was its demented dean. Comedian Nick Helm told The Guardian that in the 1970s comedians were the kings of New York. “He introduced [the idea of] funny people not just as rock stars but gods. And I think that the funniness of it maybe came second to the lifestyle. It’s hard to watch those SNL sketches and not smell the alcohol and drugs. They just smell of excess.” In one of Belushi’s most popular sketches, he is pretending to be Beethoven and after sniffing a white powder, he turns into Ray Charles. What he sniffed, live in front of 17 million viewers, was real cocaine. Belushi called it “Hitler’s drug” for the power it made him feel. He was convinced that his best impersonations, from Henry Kissinger to Joe Cocker, were due to cocaine. “The truth is that many on the show thought that you can’t do a ninety-minute live comedy show week after week without doing cocaine,” SNL writer (and future US Senator) Al Franken told People.

The budget for The Blues Brothers movie provided for cocaine, for night-time scenes. “Everyone did it, including me,” Aykroyd told Vanity Fair. “[But] John, he just loved what it did. It sort of brought him alive at night - that superpower feeling where you start to talk and converse and figure you can solve all the world’s problems.” In the documentary Belushi, there are letters the comedian wrote to his wife, promising he would give up drugs after the next movie. Belushi ended up spending $2,500 a week on cocaine. The more he earned, the more he took. And if he didn’t have money, it was given to him as a gift.

“I swear, you’d walk down the street with him, and people would hand him drugs. And then he’d do all of them – be the kind of character he played in sketches or Animal House,” the director Penny Marshall told Vanity Fair.

Some of the stories Woodward relates in his biography are as sad as they are terrifying. One night he turned up on set at SNL in such a bad state that the producer, Lorne Michaels, called a doctor, who said that if Belushi performed he may well die. “What’s the probability?” Michaels asked. Fifty-fifty, came the reply. “I can live with that.” John Landis, who directed The Blues Brothers, found Belushi found him semi-conscious, soaked in urine and next to a pile of cocaine. “John, you’re killing yourself! This isn’t financially viable. You can’t do this to my movie!” His wife, Judy, wrote to Belushi’s dealer. “I understand it’s your job, but please stop selling him cocaine.”

As Belushi had been banned from all the bars in New York, he opened his own in an abandoned building on Hudson Street. Among his regulars were David Bowie, Keith Richards and ZZ Top. “It was tiny, it smelled awful and the bathrooms were filthy… it became the most fashionable party in New York,” Glazer recalls in the documentary.

Belushi spent the first week of March 1982 in Bungalow 3 at the Chateau Marmont on Sunset Boulevard, trying to rewrite the script for Noble Rot, a romantic comedy he hoped would help him mature as an actor. Paramount instead proposed the film The Joy of Sex, a comedy that required Belushi to wear diapers. The failures of 1941, Continental Divide and Neighbors had made him feel like a Hollywood pariah. Belushi, despite being anti-system, carried positive reviews around in his jacket pocket.

Bungalow 3 became a 24-hour party. To be able to sleep, Belushi had to rent a room at a nearby hotel. On March 5, Robin Williams came by to say hello and Robert de Niro stopped for a couple of drinks, but he didn’t stay long as he was uncomfortable around the mess, with bottles, overfilled ashtrays and leftover food everywhere, and because he didn’t like, by his own description, the “tawdry woman” accompanying Belushi.

That woman was Cathy Smith, a groupie who had lived in the Rolling Stones’ mansion for a couple of years and was then running errands for rock stars. Smith had taken up residence with Belushi at Chateau Marmont with the task of injecting him with speedballs, a mixture of cocaine and heroin, because he didn’t like needles. At dawn the next day, Smith took him a glass of water in bed and he told her that he was fine but asked her not to leave him alone. But she had errands to run. When she returned, the hotel was surrounded by police, reporters and onlookers: At midday, personal trainer Bill Wallace, who was helping Belushi to lose weight, had found him dead in his bed, naked and in the fetal position. He was 33 years old.

That morning, Hollywood awoke from a party that seemed it would never end but had stopped being fun all at once. “Before that day, nobody thought you could die from it,” Franken said. Belushi became a fable, with cautionary tale included, about the moral corruption of Hollywood and the suffering of its stars. Woodward’s book definitively inscribed the myth in the folklore of the city: “He made us laugh,” the reporter summed up. “Now he’s making us think.”

Photographs from Belushi’s funeral capture a generation of comedy stars in a state of shock. Cathy Smith gave an interview to sensationalist tabloid National Enquirer whose headline, I killed John Belushi, prompted the reopening of the investigation into his death. Smith was sentenced to 15 months in prison for involuntary manslaughter. She died in 2020, aged 73. The New York Times published an obituary describing her as “one of the most notorious footnotes in pop culture.”

Chateau Marmont, which had always been a discreet refuge for the stars, entered into the black chronicle of Hollywood after Belushi’s death. With the passage of time, the coaches carrying tourists around added it to the list of obligatory stops. Bungalow 3 became a place of cult worship and pilgrimage. New York artist Jean-Michel Basquiat would always stay in Bungalow 3 during his trips to Los Angeles (he died in 1998 from a heroin overdose). In the late 1980s, writer Jay McInerney traveled to Hollywood to work on the movie adaptation of his novel Bright Lights, Big City, which was released in 1988 and starred Michael J. Fox and Kiefer Sutherland. On getting out of his taxi, the movie’s producer told McInerney he had a room reserved for him at Chateau Marmont. “Is it any good?” asked the writer. “Is it any good?” the producer replied. “John Belushi died here!”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.