France discovers Céline’s lost manuscripts and his forgotten novel, ‘War’

The papers disappeared when the anti-semitic writer escaped to Nazi Germany in 1944. They reappeared in 2020. Now Gallimard is publishing the first text

Sometimes the unexpected happens. The newspaper Le Monde calls it “a miracle.” The lost manuscripts of Louis-Ferdinand Céline (1884-1961), perhaps the most brilliant and abject of French 20th-century writers, have come to light after almost 80 years in an unknown location. The Gallimard publishing house is publishing the first of the texts extracted from these manuscripts: Guerre (War), a raw and fast-paced account of the months in which Céline was wounded in Flanders at the beginning of World War I. The author of Journey to the End of the Night has become the literary star of the year in France.

“The whole ear on the left was glued to the ground with blood, the mouth too. Between the two there was an immense noise. I fell asleep in this noise and then it rained a heavy rain,” the 150-page book begins. It was written in 1934, two decades after the events it describes. “So I always slept with a terrible noise since December 1914. I caught the war in my head. It’s locked in my head.” This is the story of a headache, an endless noise and of one of the last mysteries of contemporary French literature.

“I no longer believed that we would see the manuscripts,” admits François Gibault, who, together with Véronique Chovin, is the executor of Céline’s estate. It all started in June 1944. The Allies had just landed in Normandy. Céline was the author of several anti-Semitic pamphlets and a friend of the Nazi occupiers. Together with his wife, Lucette, and their cat Bébert, he left his apartment in Montmartre and took a train to Germany. Thousands of pages were forgotten on top of a cupboard. Someone took advantage of the writer’s departure to take them away. He would spend the rest of his life regretting the theft, and never saw the documents again.

Gibault is certain of the culprit: “It was definitely Oscar Rosembly,” he says. Rosembly, a Corsican with distant Jewish origins, was a unique character: he was a reporter, a municipal government employee and a member of the resistance who was later imprisoned for looting collaborators’ apartments. Jérôme Dupuis, the journalist who in 2021 revealed the reappearance of the papers in Le Monde, cited the “legend” that tells that Rosembly became a “guru in California” and ended his life in Corsica, meditating barefoot on the mountain and bathing naked in the town fountain.

Céline himself accused Rosembly, with whom he had spent time in Montmartre, of the theft. Nothing was ever proven. Nothing was known about the papers until June 2020, when Jean-Pierre Thibaudat, a veteran journalist for Libération, got in touch with the writer’s executors through a lawyer. His widow, Lucette, had died the year before. Thibaudat explained that he had all 5,324 sheets: the lost treasure. Someone had given them to him in the late 1980s. Who? “Confidentiality of sources,” said the journalist. Whether it was a descendant of Rosembly or someone else is unknown.

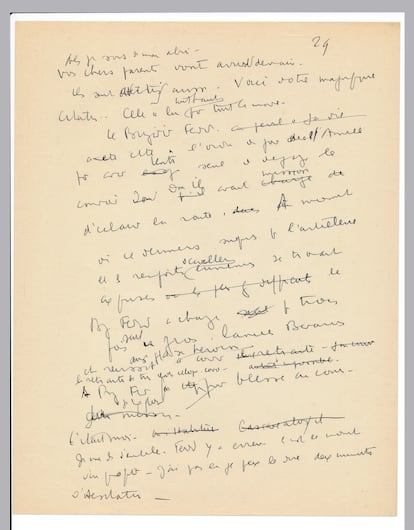

After a brief legal dispute, the executors recovered the manuscript. “When I saw them I felt excitement, satisfaction. We didn’t know what was in them, or if it was good or bad,” recalls Gibault. Now the Gallimard Gallery in Paris has some of the manuscripts on display, including extracts from the three found books, Guerre, La volonté du roi Krogold (The Will of King Krogold) and Londres (London), which recounts the author’s time in that city and will be published in October. The writing, in black ink, is almost always legible and has annotations and corrections in pencil.

Guerre is a very Celinian novel, due to the crudeness of the language, the use of jargon, the brutality of the scenes and the subject matter. “It has the major themes of Céline’s work: war and death,” says the writer Pierre Assouline. The novel’s conciseness, on the other hand, is not typically Celinian. Perhaps it is because the text was only an outline, or because it was not quite complete, but there is nothing here of the excesses, digressions and verbiage of other books. “If Céline had had the time or the opportunity to go back to the text, it would have been longer and would have lost the shock aspect,” adds Assouline. “This inconvenience is an opportunity.”

Guerre is a concentration of Céline’s signature elements. There is despair: “We know that it would take sleep to return to being a man like the others. We are too tired even to have the strength to kill ourselves. Everything is tiredness.” There is sex and misogyny. (”Le masque et la plume,” the literature program on France’s Inter network, called it “pornography” on Sunday.) There is life and memory transformed into literature: “What a shit the past is, it dissolves in reverie. He adopts little melodies that nobody had asked him for. He returns all made up between tears and laments. It’s not serious. Then you have to ask the dick for help to get your bearings. It’s the only way, the man’s way.”

Criticism is divided. Nobody questions the importance of the text, but while some describe it as a “masterpiece” and a now-fundamental book in Céline’s oeuvre, others call it an unrevised and incomplete text, a draft. “It has its value and an impact, but it is not a true Céline, because it is not finished,” says Henri Godard, a French Céline specialist. “These are texts that he had voluntarily left aside and that he did not think of publishing.”

As it has done with Marcel Proust and the previously unseen work by this other great French writer of the 20th century, Gallimard continues to reconstruct Céline’s work written decades ago but not yet completed. “The Gallimard house welcomed Céline at the most difficult moment, when he was a hated author,” says editor Antoine Gallimard, referring to the post-war period when the writer was imprisoned in Denmark, convicted in absentia in France and later granted amnesty. “When you read it today, it’s so relevant about the war,” he adds. “He is an extremely modern writer: he managed to give the most terrible things a glimmer of hope. He is never systematically horrible.”

The other pending volume includes the virulent anti-Semitic pamphlets that Céline published before and during the Nazi occupation. At the wish of the writer and his widow, they were no longer published in France, although they are available on the internet. At the end of 2017, Gallimard announced the intention of publishing them in a critical edition with a foreword by Assouline. The news sparked a wave of protests. Gallimard suspended the plans, but did not abandon them. In 2032, all of Céline’s work will enter the public domain, allowing other editorials to publish it. “We will have to think about the possibility of publishing the pamphlets,” says the editor. “I still have 10 years to go.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.