TikTok is ending music videos as we knew them: ‘Don’t strain yourself. Do the bare minimum’

More artists and record labels are promoting their work on the social network. In fact, some post so much that they no longer have time to create any new songs

On August 1, 1981, MTV began broadcasting on cable television. The first video it played was highly symbolic: The Buggles’ Video Killed The Radio Star. The music video era had begun. The genre would become central to pop culture. In the 1980s and 1990s, it gave rise to pop’s most recognizable stars, introduced a generation of cultural icons and colonized its viewers’ eyes and ears, as songs became inextricably associated with the imagery of their videos. But that culture began to decline around the arrival of the internet, if not shortly before.

“First, music videos on open channels disappeared, because record labels tried to recover their losses from pirating by charging significant amounts to broadcast them, so they could only be seen on pay TV. There was some competition for the audience, even though it was always light years away from the viewership of film, sports or documentaries. But the most torrid Latino music videos were always a good night-time option for platforms without porn. That lasted until the arrival of YouTube, which almost completely finished off those music video channels,” says Javier Lorbado, who was the director of the well-known Spanish music studio Sol Música from 1997 to 2014 and now works as a freelance digital communication specialist for artists, record labels and managers.

YouTube was born in 2005. It is now the second-most-visited website in the world after Google. With the platform’s arrival, as Lorbada recalls, “the ways of consuming videos changed, just as with films and TV series when Netflix appeared.” That made MTV start “a desperate race, completely changing its concept and forgetting that the M in their logo came from the word music. It tried reality shows, competitions, series, movies, until arriving at what it is today, a platform for all kinds of programs directed at an audience of teenagers and young people. Almost anything fits the bill, as long as it is attractive to advertisers.”

But a new paradigm shift arrived from China at the end of 2016. During the pandemic, TikTok became the most popular social network in the world. Now, the platform is threatening to set new rules for the music industry. The artist Halsey has publicly stated that her record company has prohibited her from releasing her new song “unless they can fake a viral moment on TikTok.” She joins a long list of stars who have criticized such demands, including Florence Welch, Ed Sheeran, Charli XCX and FKA Twigs. “They’re forced to constantly generate content to satisfy the current neoliberal machine. It’s always been like this to some extent, but I can imagine that now it must be really draining and hard to bear,” says Luis Cerveró, a music video director and founder of the Barcelona production house CANADA.

From Rosalía to Pink Floyd, the new viral video

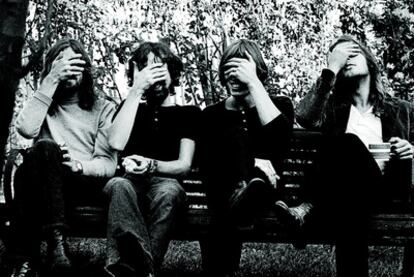

Other stars, however, have embraced the platform, fully aware of its marketing power. In March, Rosalía released her album Motomami with an exclusive performance for the social platform, including live performances of her songs and interviews with her celebrity friends. While Generation Z is TikTok’s primary audience, though, idols from other generations have also begun experimenting with the platform. Most unexpected has been this week’s news that Pink Floyd have made their entire song catalog available in TikTok’s sound library, and they will begin regularly posting exclusive videos on the platform.

“It’s more and more common for people to discover music on TikTok, and if you’re not present there, you’re going to be closing off an immense opportunity for promotion. A new generation of users who may have never heard Pink Floyd could now discover them,” says Laura Estudillo, who, after working in communications at Warner, founded the agency Panorámica in 2017 and works with artists including Chanel and Alizzz. Estudillo adds that “the most important thing is for the artist to feel comfortable with the content that they share. If they do it without enthusiasm, or it seems forced, the audience will notice it, and that can be counterproductive on platforms like TikTok. The great attraction of the platform is its unprecedented capacity for making things viral. Without even having followers, the algorithm can make you into a star, which will be reflected in YouTube videos, Spotify streams and ticket sales.”

But it also brings a paradigm shift to the video format. “TikTok creates a severe attention deficit. They are extending the time that videos can last, but they don’t work as well as the short ones, and you still can’t upload an entire song. For the artist, the content they make on the platform is an extra addition. And in the best case of TikTok success, having a viral audio considering the competition out there is almost a miracle,” says Ainhoa Marzol, an expert in digital trends. “If years ago you’d told me that content consumption would be in a vertical format, I wouldn’t have believed it,” Laura Estudillo adds. “Now even screens at festivals are adapted to the format of stories.” “As a social network, I prefer Instagram, but without a doubt, TikTok is the key right now,” says musician and performer Bea Pelea. “It lets you create cheaper, more accessible audiovisual content that can give a pretty significant push.”

The need to film music videos

In April, indie musician Javier Carrasco, better known as Betacam, wondered on Twitter: “Does it make sense to film music videos in 2022? Can you allow yourself NOT to film them?” After sharing his video for his song Norteamérica triste, he posted, “I lost a lot of money doing this, and for what? Nothing. Moral: don’t strain yourself. Do the bare minimum: a few dances for Instagram and TikTok and call it a day.” Other artists chimed in to agree with Carrasco’s Twitter thread. Today, Carrasco gives some nuance to his declaration: “At the beginning, when you’re starting out, doing a music video is something new and exciting, but as the years go by, it’s harder to dive in head-first. It’s still laborious, extra work, but at the end of the day, I think it’s worth it. It’s always a lost investment, like everything else in music, but it makes you stop for a moment and poke your head out of the sea of daily and weekly novelties,” he says.

Logically, the economic returns vary according to the artist’s popularity. For independent artists, budgets are very low: between €1,000 and €5,000 per music video, while a 30-second commercial can cost €180,000 on average. That also creates frustrations among musicians with a low profile. “I would have liked to record more videos, because they’re important to me, but I want to do cool, up-to-date things, and our economic possibilities don’t allow that,” says Bea Pelea. The business is also tough for producers: everything is done as a favor. Luis Cerveró confesses that he stopped directing videos in 2018, when his first child was born. “A week before, I finished shooting my last one, but since then I decided that I would only leave home to do paid work.” That video had a budget of €6,000, but it is almost always assumed that the money goes entirely to production. “Nobody gets paid, not the camera people, not the makeup artists. I’ve been paid twice in my life to make a video, and I’ve made more than 60. One time very early in my career, I shot a Niños Mutantes video and I kept the entire budget, because I really needed it, and the other time is when I did the second Pharrell Williams video [Come Get It Bae] because I I felt really stupid shooting the first one [Marilyn Monroe] and not charging anything for it.” Cerveró was one of the millennium’s most in-demand independent music videos directors, and he has worked with international artists such as Battles, Liars and Javiera Mena.

“For an artist, it is essential to keep thinking about having the largest possible number of videos of all their releases,” says Javier Lorbada. “It may no longer be so important to have a large budget to make an old-fashioned music video with meticulous photography, makeup, hairdressing, lighting, special effects and amazing editing. The digital world constantly demands new content in order to achieve greater exposure and reach the largest possible number of viewers. That forces artists and their companies to constantly post new music videos of the same song. In addition to the video clip, many have lyric videos, visualizations, duets, studio versions, at home, acoustic, in the rehearsal room. The truth is that this strategy works. The more videos you have, the better results you get.”

“If we talk in economic terms, it is very difficult to make a profit,” says Laura Estudillo. “You have to be very well-positioned to be able to monetize it. For labels that cover the costs, it is also difficult to earn back their investment, but they generally have more muscle to put together digital marketing campaigns that help them get views. There are more and more artists who decide not to make videos, but even so, it is still a good promotional tool. You can get more attention in digital media if you release a song with a video. You can promote it on platforms by adapting the format to small or vertical clips, and, above all, it continues to be one of the most efficient tools that a group has to present itself to an audience. I think of Rosalía or C. Tangana as current referents of Generation Z who have been able to build very powerful iconography around their image, and the importance of their videos is undeniable. Although the platforms allow us to give the artist another dimension through photos or stories, music videos continue to have the strength of placing the artist in a utopian, highly aspirational dimension.”

“In the 1980s and 1990s the video clip explored itself as art and played with it a bit. But I think that this is all outdated today. Its function is more aesthetic. It serves, above all, to mark or emphasize the tone that the artist wants to give to their own image,” points out Ainhoa Marzol. “But I don’t think it’s going to go away. Music is a sentimental industry that is really fond of doing things the way they’ve always been done. What I do think is that the form will expand. We are already seeing videos adapted to Spotify, others with key moments to play on TikTok. If the metaverse goes anywhere,, I would imagine some more interactive video clips within it, perhaps similar to albums in the format of video games, like Sayonara Wild Hearts,” the journalist concludes.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.