‘Physical Graffiti’ turns 50: How Led Zeppelin built a double-album masterpiece

Despite setbacks, with John Paul Jones threatening to leave the band and Robert Plant under the knife, the English quartet, spurred on by Jimmy Page, recorded a revered set of songs

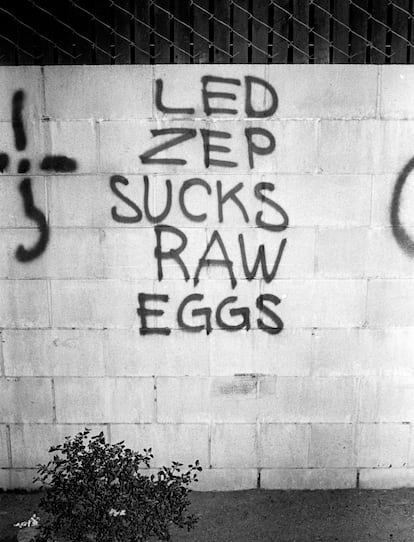

In the mid-1970s, Led Zeppelin best represented the canonical excesses of a successful rock band: shaggy-haired guys traveling in private planes, prone to unleashing barbarism in hotel rooms, and entertained by female fans and drugs. They also recorded sensational albums that they presented to audiences of thousands. But the British quartet’s narcissism still needed more. For example, a double album, something that figures like Bob Dylan (Blonde on Blonde, 1966), The Beatles (White Album, 1968), The Jimi Hendrix Experience (Electric Ladyland, 1968), The Who (Tommy, 1969), and The Rolling Stones (Exile on Main Street, 1972) had already done, to excellent reviews. Led Zeppelin’s frontman, guitarist and songwriter Jimmy Page, longed for the status that a two-record, four-sided album provided. But some challenges arose in the process: bassist John Paul Jones wanted to leave the band; vocalist Robert Plant had to undergo surgery to remove lymph nodes, and no one knew how the procedure would affect his voice; and drummer John Bonham was beginning to suffer the consequences of years of alcohol abuse. Physical Graffiti began its journey in this uncertain environment.

The negative reviews of the band’s previous album spurred on Page, who was as arrogant as he was competitive. Of that album, Houses of the Holy (1973), critic Gordon Fletcher wrote in Rolling Stone: “It’s one of the most boring and confusing albums I’ve heard this year. Even after 100 listens, I’m still not convinced that this album is from the same group that recorded songs like Communication Breakdown, Heartbreaker, or Black Dog."

The making of Physical Graffiti started with just 50% of the band. Page and Bonham met at Headley Grange, the former workhouse converted into a country house where the band had previously recorded Led Zeppelin IV and Houses of the Holy. In truth, Page longed to recapture the spirit of IV, their magnum opus. Plant’s surgery went well, and after being unable to speak for a month, he began joining the sessions at Headley Grange. In Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography, British writer Chris Salewicz provides insight into the change in Plant’s vocal cords: “His singing on Physical Graffiti is different from Zeppelin’s previous recordings: it sounds more comfortable, controlled, and accomplished, with much of the same raw power still present, but very rarely verging on the bitch-in-heat wails of yesteryear.” Still to be resolved was Jones’s departure, brought on by a nervous breakdown after the grueling pace of the previous years. Jones needed to spend time with his family, to disconnect from the lascivious life of rock, an environment his bandmates enjoyed much more than he did. The bassist considered his options and returned to Led Zeppelin, but not before receiving a promise from Page that the atmosphere would be more relaxed. That would never come to pass (it only took place after Bonham died, aged 32, as a result of a massive drunken binge in 1980), but the reunion of the four members was a done deal. Work on Physical Graffiti could begin.

The now-complete group immersed itself in a special atmosphere of creativity, and the songs began to emerge, some of them already worked on instrumentally by Page months earlier. Although many tracks were recorded, the result fell short of a double album, so the guitarist had to delve into the sessions of previous albums to fill the gaps. Some were of high quality, such as The Rover, Down By the Seaside, and Night Flight, while others were less interesting, such as Boogie with Stu (a rock ‘n’ roll track with piano by Ian Stewart, the Stones’ official keyboardist) or Bron-Yr-Aur (a series of arpeggios by Page on acoustic guitar).

What makes Physical Graffiti one of rock’s finest double albums is the exuberance of the tracks that emerged from those 1974 days at Headley Grange: the electric immediacy of Custard Pie; the 11 minutes of ghostly blues of In My Time of Dying, an even more lustful response to the Stones’ 1969 Midnight Rambler; the Stevie Wonder-inspired organ-driven funk of Trampled Under Foot (decades later exploited by Franz Ferdinand); the excellent mid-tempo Ten Years Gone, with Page’s effortlessly caressing guitar solo along the strings, his heart leading him into his hands; the hypnotic psychedelic blues of In the Light; The Wanton Song and its three distinct guitar melodies; or Sick Again, which closes the album and whose initial guitar riffs paved the way for Angus and Malcolm Young.

And, above all, Kashmir, eight and a half minutes of melodic frenzy, with musical substance to delight in listening to it again and again. Surely the trip that Page and Plant took through Morocco in 1973 inspired the music and lyrics of the song, co-written by Bonham, one of only two tracks in Zeppelin’s entire discography penned by the trio (the other being Out On the Times, from Led Zeppelin III). In Kashmir, one can appreciate Plant’s “restrained” and nuanced way of singing after surgery. The relevance of the song was highlighted by the vocalist when he stated years later: “I wish I were remembered more for Kashmir than for Stairway to Heaven. It’s so precise... There’s nothing pretentious, no hysteria in the vocals. The perfect Led Zeppelin." The conclusion? Physical Graffiti offers an enhanced and especially inspired showcase of all facets of the group.

“Physical Graffiti has enormous importance in the band’s history, so much so that Robert Plant said it was his favorite album, and it probably represents the band at its most creative,” Madrid-based guitarist Jorge Salán explains. “It’s considered the pinnacle of their career,” says British author Mick Wall in his book Led Zeppelin, When Giants Walked the Earth, where he also notes Page’s usual unstated “borrowings.” “The most notable example is Custard Pie, credited to Page and Plant, but whose harrowing introduction is reminiscent of I Want Some of Your Pie (1939) by Blind Boy Fuller.” Bertha M. Yebra, editor of the historic Spanish magazine Popular 1, attended one of the concerts on the Physical Graffiti tour, in Brussels in 1975. “I remember being in the front rows, very close to the stage, when I saw Plant with his wonderful look, his long blond hair, his special elegance, his voice, his poses. In those years, he was the biggest star on stage. Jimmy Page was natural and charismatic; John Paul Jones and Bonham were also excellent instrumentalists. I can say without exaggeration that it was one of the most amazing concerts of my life. Their sound seemed to have come from another galaxy,” the Catalan editor tells this newspaper.

Physical Graffiti was the band’s first release on their new label, Swan Song Records. After finishing their contract with the industry giant Atlantic, the bold and aggressive negotiator Peter Grant, the group’s manager, wrested a lucrative deal from Ahmet Ertegun’s multinational: to have their own record label under the Atlantic umbrella. The label’s launch parties in 1974 portray the opulent life of those Zeppelin members: ostentatious gatherings in expensive hotels (two events were organized, in Los Angeles and New York) with strippers, fire-eaters, magicians, pink flamingos... In addition to many musicians, Groucho Marx attended the party at the Hotel Bel-Air in Los Angeles. When he was introduced to singer Maggie Bell, she said, “It’s an honor to meet you, Mr. Marx.” Groucho responded, “Screw that! Show me your tits!”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.