The bittersweet story of the song that ended ‘Britpop’

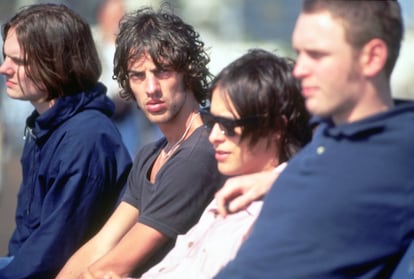

‘Bitter Sweet Symphony,’ the smash hit by The Verve, turns 25 after healing from some of its wounds, such as the fierce fight with the Rolling Stones for royalties. The song’s performers remain in the shadow of its success

In the music video for The Verve’s Bitter Sweet Symphony, a man walks down the street alone complaining that “life is a bittersweet symphony.” When it was released on June 11, 1997, it was immediately clear that the song was destined to make history. At a time when radio still played a major role in musical success, the song had constant airplay. It brought the band, led by Richard Ashcroft, to the forefront of Britpop just as the movement was breathing its last. After the Oasis concert at Knebworth the previous summer, as Blur turned towards American-influenced indie rock on their self-titled album and Radiohead changed the paradigm with OK Computer and The Prodigy with The Fat Of The Land, the hegemony of the sound associated with Cool Britannia was one step away from dying. Bitter Sweet Symphony, with all its majesty, its existential reflections, its ambition, its loftiness, its length of over six minutes and its iconic aura, was the genre’s last great anthem, Britpop’s swan song.

The video clip undoubtedly influenced the song’s success. Its director, Walter A. Stern, in fact wanted to pay tribute to Massive Attack’s Unfinished Symphony, another definitive nineties anthem whose video had the same structure. In this case, Ashcroft’s attitude not only demonstrates an extreme stubbornness, but also an exaggerated individualism characteristic of the time, with the protagonist completely oblivious to everything around him. The video elicited a wide range of interpretations, including one theory about the shot when the protagonist stops to let through a car with tinted windows, said to have been a tribute to his friend Noel Gallagher. Oasis started their career opening for The Verve, then did the reverse when they became famous, and the frontmen of both bands had dedicated songs to each other (Cast No Shadow and A Northern Soul) on their respective 1995 albums. The video also spawned a mythical route for fans who followed the path as if it were their own Abbey Road. (This one was a loop through Hoxton, Purcell and Crondall streets in East London.)

The experimental group with a cult following

The Verve was founded in 1990 in Wigan, a city in the Manchester belt famous for having been the site of the Wigan Casino, the Vatican of a 1970s movement called Northern Soul. The group’s rise was linked to the Madchester Sound and the style known as shoegaze. Their first albums were dense atmospheres of saturated psychedelic guitars. After several EPs and two albums (A Storm In Heaven in 1993 and A Northern Soul in 1995), the creative and personal conflict between guitarist Nick McCabe and the vocalist, who wanted to leave behind the group’s more experimental side, led the former to dissolve the group. It wasn’t the first time he’d done so, nor the first time he’d reconsidered. He knew that he had an ace up his sleeve that could change things, and that to complete the mission he needed his bandmates.

Bitter Sweet Symphony was the first single from Urban Hymns, a third LP for which the band recruited as producer Martin Youth Glover, a member of Killing Joke and The Orb who was becoming one of the most renowned technicians in British pop. The event was closely associated with one of the great scandals that dazzled the British press at the time: two years earlier, Ashcroft had secretly married Kate Radley, the girlfriend of Jason Pierce of the band Spiritualized. Radley was still a member of Pierce’s group, which simultaneously released another of the year’s most acclaimed albums, the despondent Ladies And Gentlemen, We’re Floating In Space.

“I wasn’t actually the first option. Before me, they tried a couple of other producers. I came to the recording recommended by Kate,” recalls Youth from the home studio that he currently owns in Granada. “And that’s where my life changed. I had already worked on some successful albums, like Together Alone by Crowded House, but Bitter Sweet Symphony is one of the best songs ever recorded. It is still appearing on many lists of all kinds. There are very few pop hits that have an impact like that.”

Some consider The Verve to be a one-hit wonder, but that’s far from the truth. In fact, the song only reached number two in sales in the United Kingdom. The band’s next single, The Drugs Don’t Work, was the only one of their career to reach number one. “The amazing thing about Urban Hymns is that Richard came up with all these amazing songs. He had left behind the space rock improvisations that characterized the band and came out with more concrete pop songs. Even his B-sides were better than the best tracks on other people’s albums,” says Glover. “Owning that material made it all very easy, so my biggest challenge as a producer was to let the songs soar, to do them justice.”

The controversy with the Stones

But working on Bitter Sweet Symphony was complicated and almost traumatic. It was Richard Ashcroft’s idea to build his unmistakable string sound through a sample of the Rolling Stones’ The Last Time, using not the best-known version, but one included in an orchestral album by producer Andrew Loog Oldham. The sample led to one of the most talked-about intellectual property lawsuits in pop history.

The original sample was just five looping notes, and the song was released before the Rolling Stones office approved it, as The Verve’s record label thought there would be no problem. It was a big mistake. Seeing that the single’s success was blowing up, Allen Klein, the manager of the Stones, went on to ruin the band’s lives. The Verve believed that the rights would be divided 50-50, but Klein, who is said to have left the lawyer’s office with a smile worthy of a movie villain, got 100%. All authorship of the song was credited to Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Andrew Loog Oldham, despite the fact that the Stones’ vocalist and guitarist had contributed absolutely nothing. The musicians of The Verve weren’t the only ones affected: David Whitaker, the true composer of the string arrangements sampled, was also excluded from authorship.

The recording was a meticulous piece of work, as Youth recalls. “Richard didn’t believe in the song at first. There was a version prior to my arrival, and I encouraged him to try recording it again.” The producer emphasizes that the Loog Oldham sample is not as noticeable in the final version, since it is hidden among almost 50 layers of instrumentation. “I persuaded a string section to play the melody over the top, with new arrangements, without Richard knowing, at a time when he wasn’t in the studio. I knew it would be worth it, even if he got mad,” he says. On the appropriation by the Stones, he says that “it was very unfair. It is true that we reproduced the same melody and the same arrangements. It can be understood as a version. But Richard wrote a completely new lyric and deserved more credit.” He ironically declared that Bitter Sweet Symphony was “the best Rolling Stones song since Brown Sugar” after it was presented at the Grammy Awards ceremony as a Jagger and Richards composition. Not only did the Rolling Stones get all the credit and the economic benefit, but their manager also had all the power over the song’s licensing for commercials and movies. When he allowed its use in a Nike campaign, Ashcroft flew into a rage.

Urban Hymns was a huge success at all levels. That year, The Verve packed all the big venues in which they performed, but the dispute over their emblematic song’s authorship remained stuck in the vocalist and led him into depression. The band did not last much longer together. In 1999, its leader announced its dissolution with a phrase worthy of Morrissey or the Gallagher brothers: “It is more likely that you will see the four Beatles together on stage again than The Verve.” But in 2007, they came back again for a couple of years, recording a fourth album and doing another tour, the last one so far. Ashcroft began a solo career that enjoyed considerable commercial recognition, especially at the beginning, but always under the long shadow of Bitter Sweet Symphony. New musical icons like Chris Martin recognized the group’s impact on the following generations. At Coldplay’s Live 8 mega-event concert in 2005, their frontman invited Ashcroft on stage to cover the song with him, after presenting it as “probably the best song ever written.” The leader of The Verve kept fighting for his authorship, and the story finally had a happy ending: in 2019, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards agreed to revoke their rights and acknowledge that the song was by Richard Ashcroft.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.