How Charlton Heston played a gay man without knowing it in ‘Ben-Hur’

Sixty years ago, the writer and director of one of the most popular films in history made sure that a major Hollywood star wouldn’t find out that his character was in love with another man

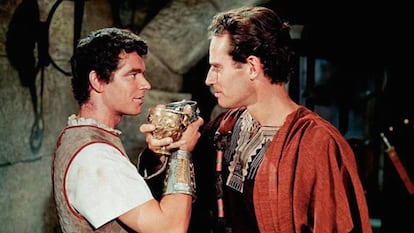

Two men encounter each other once again after years of separation. Judah Ben-Hur and Messala cannot contain their joy: they grab each other by the arm, gaze into each other’s eyes and look one another over with a half-smile. They brush hands as they share a drink, and they laugh nervously.

Their exchange could be understood as a declaration of love: “After so many years, still close.” “In every way.” “I said I’d come back.” “I never thought you would. I’m so glad.” The scene culminates with Ben-Hur and Messala sipping wine from their chalices with the arms interlaced, staring at each other intensely. According to the writer of Ben-Hur, considered the greatest movie about Romans ever filmed, the two men had been lovers. Charlton Heston, who played Judah Ben-Hur, reacted furiously when he was spoken to about the homoerotic connotations. Today, 60 years after the film’s release, its interpretations are passionate and divisive.

In The Celluloid Closet, a 1995 documentary about the LGBTQ+ presence in film, the scriptwriter Gore Vidal explained that he wrote Ben-Hur with the intention of suggesting that the rivalry between Messala and Ben-Hur was born from a youthful affair. “You had to be really good about projecting subtext without saying a word about what you were doing,” Vidal remembers in the documentary, noting that the only way to maintain the tension through the several-hours-long film was to establish that they had been lovers.

The director, William Wyler, accepted the idea, but there was an obstacle: Charlton Heston. Wyler feared that the film’s protagonist, one of the era’s most conservative stars, “would fall apart” if he discovered the plot point. “I’ll take care of him,” said Wyler. “Don’t say anything to Heston.” They had struggled to find a lead character: Burt Lancaster found the script intolerably boring, and Paul Newman didn’t want to show his legs. They couldn’t risk Heston getting nervous and leaving them without a leading man.

The solution was to explain the romantic past to Stephen Boyd, who played Messala, but hide it from Heston. During the filming, everyone knew but him. Vidal remembered how Heston mimicked the dignified posture of Francis Bushman in the 1925 production of Ben-Hur, while, he recalls, “Stephen Boyd is acting to pieces. There are looks that are just so clear.” Boyd and the rest of the crew found it funny to form part of the secret.

In a letter to Vidal, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer publicist Morgan Hudgens mentioned the set-up: “The big cornpone [the crew’s nickname for Heston] really threw himself into your ‘first meeting’ scene yesterday. You should have seen those boys embrace! I’m afraid CH is definitely coming off Secunda in that battle of profiles.” And towards the end of the film, the fervor with which Messala and Ben-Hur compete in the chariot race, with Messala cracking a whip left and right, acquire much more physical connotations when seen through another lens.

When Heston heard Vidal’s comments in The Celluloid Closet, he began a crusade to discredit them. He defined the revelation as “ridiculous” in Time magazine, and he called the documentary’s producer to deny that Ben-Hur was a homosexual. Gore Vidal responded in an article in which he referred to Heston as “proud trumpet for the National Rifle Association.” “What is one to do with an old actor who, when he works, often wears two toupees, one on top of the other in the interest of verisimilitude?” Vidal wrote.

Heston responded in the L.A. Times: “Vidal’s claim that he slipped in a scene implying a homosexual relationship between the two men insults Willy Wyler and, I have to say, irritates the hell out of me.” The actor discredited Gore Vidal, saying that he only worked on Ben-Hur for three days and that his contributions were discarded. That version contradicts Heston’s own autobiography (The Actor’s Life, 1978), in which he recounts, “Today we rehearsed Vidal’s rewrite of this crucial scene with Messala [Boyd]. Indeed the crucial scene of the whole first half of the story. . . . This version is much better than the script scene.”

The film historian Michael G. Cornelius, an expert on peplum movies (featuring stories about ancient Greece and Rome), and editor of the collection Of Muscles and Men: Essays on the Sword and Sandal Film, describes this type of subtext as a code that appears only in the highest works of art, a message that does not modify a piece’s more explicit content but rather complements it. Those who decipher the code will see more than those who prefer to remain on the surface and simply enjoy the main story.

“What makes Ben-Hur unique is that its subtext appears in the dialogue, which allows for a sincere consideration on behalf of the spectator. In most peplums, the homoerotic subtext is visual, which is more obvious but also more easily discarded,” Cornelius explains to ICON.

“What really sets apart the peplum is that the central theme of these films is the male form,” Cornelius continues. “The male body appears on show. Other genres are interested in exploring masculinity, but Roman cinema has risen as a study of the masculine and, in particular, the masculine form.”

But gay audiences’ interest in Roman movies goes beyond innuendo or sexualized aesthetics. (As Cornelius points out, “we’re talking about half-naked, muscular men running around in leather skirts and sweating around hordes of other similar men.”) They are also epic stories of social justice. “Apart from representing the zenith of masculinity, these heroes also reflect notions of justice, community and inclusion. They represent a progressive and inclusive society. They create communities that gays feel they could belong to. And that makes a positive and powerful impression.”

Ben Hur, the most expensive film in history at the time, ended up winning a record 11 Oscars. Charlton Heston won for best actor, while Stephen Boyd, who had won the Golden Globe, was not even nominated. The only nomination the film did not win was for best adapted screenplay. The film also triumphed at the box office, and it became the second most successful film in history, only behind Gone with the Wind.

Today Ben-Hur remains a classic of Easter movies and a relic of Hollywood’s most ostentatious times. But it also remains a symbol of a time when minorities had no voice of their own. They could only whisper and hope someone would hear. Hollywood has always been a dream factory, but sometimes you have to be wide awake to understand what’s behind the curtain.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.