The fight against hepatitis in Africa hangs in the balance after US cuts: Clinics closed, fewer tests and canceled research

Up to 40% of organizations report ‘major impacts’ on their work, according to surveys by the Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination and other groups, which warn of the risk of rising cases and severe liver disease

The cuts to foreign aid ordered by the United States government have wreaked havoc on the fight against hepatitis in Africa. Clinics dedicated to treating hepatitis B and C have been forced to close, thousands of aides who provided free diagnostic testing have been laid off, and medication supplies have been disrupted. The impact on the 72.5 million people in Africa living with hepatitis B and C is difficult to quantify precisely because the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and other institutions did not allocate a specific budget for combating these diseases. These resources, however, reached organizations through HIV‑related programs, since both conditions are transmitted through blood and sexual contact.

As a result, when the Donald Trump administration suspended USAID and temporarily paused the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), it also caused “major impacts” on up to 40% of the organizations working to combat hepatitis, according to a survey conducted by the Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination (CGHE), the World Hepatitis Alliance (WHA), and the team at the Hepatitis Elimination Laboratory (Plan‑B). The main findings were published in a Lancet column late Tuesday.

Responses from 240 researchers, health workers, and organizations between March and October 2025 revealed that 30% of the groups experienced “a high impact” on clinical care for their patients, and 40% faced serious difficulties in continuing research and clinical trials. Not all sources contacted completed the survey, and some even requested anonymity for fear of losing the few donations they still receive.

Marion Delphin, one of the authors of the publication and a postdoctoral researcher at the Francis Crick Institute in London, says they received alarming reports from several African countries. “In Malawi, more than 1,500 testing aides were laid off at the end of 2025. This halted community testing and forced clinics to close, leaving people without access to care or prevention,” Delphin tells EL PAÍS via email. “We have numerous reports of antiviral shortages in several countries, and of community associations and support groups severely affected by the loss of funding due to shifting priorities,” she adds.

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver that, if not diagnosed early or treated properly, can lead to severe liver damage or cancer. There are five strains of the virus that causes the disease, but types B and C in particular affect 304 million people worldwide and kill 1.3 million every year. Of those deaths, 943,000 occur in Africa, according to the WHO. Even before the cuts, however, the fight against the disease on the continent was already in a critical state. Fewer than 5% of people with hepatitis B have been diagnosed, and of those, only 5% have received treatment. Africa also has the lowest coverage of birth‑dose vaccination against the B variant: barely 8%.

In this context of extreme fragility, the decline of hepatitis care coincides with a broader shift in U.S. health policy. In December, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — whose experts are appointed by Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. — voted to recommend against universal hepatitis B vaccination for newborns. The government also backed a controversial study in Guinea‑Bissau that proposed leaving some infants unvaccinated, an initiative that was blocked after ethical objections from the WHO.

The problem, organizations warn, is that reduced screening, treatment interruptions, and declining vaccination rates could lead to a rise in cases, worsening outcomes for patients with more aggressive liver disease, and the emergence of drug resistance. Delphin explains that interrupting treatment for chronic hepatitis B can trigger “viral rebound, inflammation, and hepatic decompensation, and in severe cases, death.” If birth‑dose vaccination declines, she adds, the risk of mother‑to‑child transmission increases — the main route of hepatitis B transmission in sub‑Saharan Africa.

If preventive services are limited, she continues, the burden on health systems grows as they are forced to deal with liver failure, cancer care, hospitalizations, and transplants. “We needed to increase testing, outreach, and access to care, not reduce it,” Delphin insists.

Doing what they can with fewer resources

The NGO Kiraay, which operates in Senegal, is among those affected. Until now, the organization had worked under the umbrella of large coalitions of community groups in Senegal that received funding for HIV programs. With those resources, the NGO cared for patients with HIV as well as those with related conditions such as hepatitis. But after the cuts, the little it was able to do is now hanging by a thread.

“We have advocated for hepatitis to be included among the Global Fund’s priorities [which also faced cuts],” says Fatou Poulh Sow, Kiraay’s leader, via WhatsApp. At the same time, they have tried to seek support from regional donors, but so far, they have received no response.

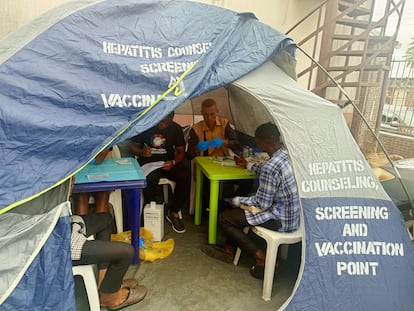

David Irinam, head of the NGO Bekwarra Hepatitis B Support in Nigeria, laments having to work “with next to nothing” in a country where more than 14.3 million people live with chronic hepatitis B and 1.3 million with chronic hepatitis C. Since 2023, the organization has led awareness campaigns, offered free testing, and referred hepatitis patients to health centers in Cross River State (population four million), where a high prevalence has been detected.

“Donald Trump’s foreign policy affected us greatly; services were disrupted, and we couldn’t continue our community outreach programs. We couldn’t test residents in some of the communities we planned to visit, which are very difficult to access,” Irinam explains from Bekwarra in a phone call. In one campaign, for example, they had planned to conduct 12,000 tests, but only completed 6,000 because there wasn’t enough money to travel to remote villages.

Irinam, a microbiologist and pharmacist dedicated to fighting hepatitis in Nigeria, adds that the cuts have also made it harder for patients to obtain medications at lower prices. “In this region, the average person lives on less than a dollar a day. And antiretrovirals cost around 30,000 naira a month [$22]. People can’t afford that, nor the cost of traveling to see a doctor,” he explains.

Although Bekwarra received support last December from the Hepatitis B Foundation USA and the African Hepatitis B Advocacy Coalition (ABAC) for awareness activities and free testing, she says it’s not enough given the scale of the problem. “That’s why we’re advocating for government intervention [in Cross River],” she adds.

Prince B. Okinedo, co-founder of ABAC, which launched a year ago, explains that the ABAC was able to award grants to 11 community organizations, including Bekwarra. “It was the first time some of them had received grants [for hepatitis programs],” Okinedo points out in a video call. “But it could have been many more,” he acknowledges.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.