Spain’s excommunicated nuns of Belorado: ‘We have enough to deal with just getting through life’

Of the 16 Poor Clares who were in the monastery when they split from the Church, only seven remain, awaiting an eviction scheduled for March 12. It is the latest chapter in a struggle involving real estate, restaurants and schismatic leaders

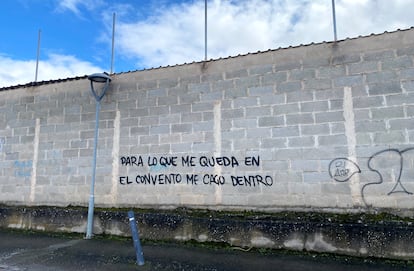

“Private Property. No Trespassing,” reads the sign at the entrance to the Monastery of Saint Clare of Belorado. The gate is locked. Inside are the nuns who, on May 13, 2024, broke with the Roman Catholic Church, which entails excommunication. They have no intention of leaving, but on March 12, they will be evicted by court order, with backup from law enforcement if necessary. “If you wish for assistance, please call this number,” reads a second sign hanging below the first. On a side door, there is graffiti that urges them to “Occupy and Resist.” About 100 meters away, someone has scrawled on a huge wall: “Considering what little time I have left in the convent, I might as well take a dump in it.” The street that runs parallel to Camino Monjas (Nun Road, the one leading to the monastery), is Camino del Matadero (Slaughterhouse Road).

Perhaps this is the scene that best describes the situation at Belorado, in Spain’s northern Burgos province. The case of the rebel nuns, initially seen as an eccentricity that attracted worldwide media attention, has become an endless legal battleground of civil and criminal lawsuits in which even the Holy See has intervened.

On Monday the sisters launched a website, queremosunconvento.com (wewantaconvent.com) appealing to the solidarity of the Spanish people and the empty expanses of rural Spain to find a new place to live if the eviction goes ahead.

According to the archdiocese, in ecclesiastical law, expulsion from consecrated life entails the loss of the legal status under which they lived in the monastery. The nuns’ defense, however, argues that Spain is not governed by canon law. “When each of them, as individuals, decided to separate from the Catholic Church, the Monastery, as a legal entity, also separated, so that neither they nor the Monastery are subject to canon law anymore, and therefore the Archbishop of Burgos ceases to have jurisdiction over them and the Monastery,” explains one of their lawyers, Florentino Aláez.

Upon splitting from the Church, the Poor Clares intended to transform the religious entity into a civil association and requested its transfer to the National Registry of Associations. The Ministry of the Interior denied the request after asking the archdiocese for a report to determine if it complied with the law.

The Holy See appointed Mario Iceta, Archbishop of Burgos, as pontifical commissioner, a kind of legal, financial, and administrative guardian of the three monasteries belonging to the Order of Saint Clare—Belorado, Derio, and Orduña—and which the Poor Clares are claiming as their own.

In the 70 pages of their Catholic Manifesto, the abbess explained that the decision to break with the Church had been under consideration for “many years” until reaching the “empirical conclusion” that all Church doctrines after the Second Vatican Council were invalid; the authority of the popes following the Council was denied, and Francis was declared a “heretic.” They placed themselves “under the guardianship and jurisdiction” of Pablo de Rojas Sánchez-Franco, excommunicated in 2019 and leader of the Pious Union of Saint Paul the Apostle, which Rome as well as religious experts consider to be a sect.

Since the publication of that manifesto, all sorts of things have happened: to begin with, an audition to recruit someone to attend to the needs of the daily liturgy. Candidates who applied included a priest known for his past as a bartender in Bilbao, an Argentinian boxing expert, and a priest from Valencia who had been ordained illegally.

Other things happened along the way: the opening of a restaurant that didn’t even last a year, a night in jail for two of the rebellious nuns, investigated for misappropriation of cultural heritage, and a second investigation into possible illicit activities in the sale of 1.7 kilos of gold for €121,000. There was also a rescue by the Civil Guard, achieved only on the third attempt, of the most elderly residents of the convent: five nuns between 87 and 100 years old, known as the non-schismatic ones.

The workshop where they produced and sold their famous truffles and chocolate sticks closed in May of last year. According to their lawyers, the schismatic nuns currently live off the “very profitable” business of breeding dogs and other animals that they already owned before the schism, and “survive thanks to the support of their families.”

Of the 16 cloistered nuns who were living in the monastery when the abbess signed the manifesto to sever ties with the Catholic Church, one left the next day. Five of the oldest did not ratify the decision, and now, a month before the eviction, only seven remain: Sister Isabel (the signatory on behalf of all), Sister Sion, Sister Berit, Sister Paloma, Sister Belén, Sister Israel, and Sister Alma. The oldest of the group is 61 years old.

One of them, who declined to identify herself to “protect” her “privacy,” returned this journalist’s call 24 hours after dialing the phone hanging on the gate of the compound some 20 times. The idea had been to meet with them to hear in their own words how things got to this point. “Media affairs are handled by a manager [Francisco Canals]. We prefer it that way,” she said sweetly on the other end of the line.

“The last thing we want is to be denigrated any further”

Told that this newspaper had already tried the press officer four times without success, she replied: “I’m sorry, it’s nothing personal. At first, we tried to do exactly what you’re suggesting, to speak out ourselves, but it was worse. We’d say one thing, and three seconds later, they’d say another. They even set a trap for me. And that’s been very hard. We’re a bit burned out, and the last thing we want is to be denigrated any further. Besides, EL PAÍS isn’t exactly aligned with our views.” Then she added: “The situation right now is very difficult. We have enough to deal with just getting through life. What’s the point of us going on EL PAÍS to deny everything that’s being said in the media? It’s all a lie...” As she hung up, she urged this journalist to follow their Instagram account [@tehagoluz]: “We speak out there.”

Of the 10 rebels, only seven remain. Aláez, the lawyer, elaborates: “What I don’t know is how the others have withstood the tremendous pressure from the archbishop, who intended to do them as much harm as possible. Discouragement, the struggle with the Church… There are many factors involved.”

Faced with the imminent eviction, this newspaper has been unable to obtain the rebels’ version of events. The nun who returned the call only listed one of what she considers to be “lies.” “It has been written that we beat the older sisters and kept them in deplorable conditions,” she laments.

When the abbess claimed to be signing the separation manifesto on behalf of all 16 Poor Clares in May 2024, she did not actually consult the others, or at least not the dependent or elderly sisters. This is how Carlos Azcona, secretary of the managing commission appointed by the Pontifical Commissioner, explains it. “We know that she is the only one who signed it because we were told by Sister Amparo, who left precisely because she disagreed with that way of doing things.”

What Sister Amparo recounts—and which this newspaper has corroborated with the niece of another non-schismatic nun—is a script worthy of a television series. “She didn’t summon us to present the agreement to us; she simply called us all on May 12, the day before making it public, to introduce us to our new bishop,” she said, according to Azcona. That new bishop was the excommunicated Pablo de Rojas Sánchez-Franco. Sister Amparo, again according to Azcona’s account, told them that their only bishop was Iceta, and at that point they asked her to leave the convent.

The niece of one of those five elderly nuns, who asked not to be named to “protect her family’s privacy,” told this newspaper: “It was impossible for the five older nuns to agree to that because some, like my aunt, were already in a state of dependency that prevented them from contradicting those who made the decisions. They couldn’t decide anything on their own because they weren’t capable of doing so. They didn’t realize what was happening around them. They were affected emotionally by the tension and the unusual activity; they were used to the peace of the convent. I think a small group of two or three manipulated the rest. They’re like a cult,” she recounts. This niece was “expressly” forbidden, from a certain point onward, from visiting her aunt. “The relatives of those who agreed with the manifesto have been at the convent almost constantly.”

Abbess Isabel’s term was her fourth, Azcona explains: “It had already been extended with the Holy See’s permission for two more three-year periods, which is the maximum allowed. The last term was expiring at the end of May 2024, and she could not be re-elected. The manifesto was presented just a couple of weeks before that…” Enrique García de Viedma Serrano, a lawyer and the abbess’ brother, maintains in a phone conversation that the nuns have not regretted their decision. “They knew the Church wouldn’t take it well, but what they didn’t expect was such a horrible and cruel reaction. The [pontifical] commissioner [Iceta] has wielded immense power over them, their finances, and their resources, treating them in such an inhumane way.”

When asked about this, the archdiocese says they would like to know exactly how and when the women were mistreated. Azcona stated: “They left the Church of their own free will. We respect that, but leaving has legal consequences. We tried to talk to them about their needs, but when we showed up there, they called the Civil Guard and kicked us out. We then gave them an email address so they could request anything they needed: diapers for the older ones, food, medicine. They only sent us traffic tickets and unpaid bills.”

Azcona asserts that when the archdiocese assumed financial oversight of the three monasteries, a disastrous financial situation came to light and that “€450,000 have been deposited from the Federation of Poor Clares to partially cover the shortfall.” He adds that when the nuns refused to turn over the monasteries’ accounts, they had to go “bank by bank” to inquire whether they had any accounts in the Poor Clares’ name in order to “determine which ones” to take over. He continues: “There were unpaid fines from the dog breeding operation, which was illegal at the beginning, payment demands from suppliers… We also had to regularize the payrolls of workers such as the caregivers and gardeners…”

There are no nuns at the Derio monastery. It’s closed, according to lawyer Florentino Aláez. They have been moving to the Orduña monastery in the Basque Country, although some residents say they haven’t seen them for a while. The older nuns were moved there last summer, before being rescued by law enforcement. The large house next to the Orduña convent looks completely abandoned and doesn’t seem habitable. There are broken windows. One doorbell is off the hook, and another isn’t, but neither one rings. The area where pigs and other animals used to be kept is muddy and also appears completely abandoned. The abbess’ brother believes this could be one of the possible sites for their relocation, “depending on their resources.” Eviction from the Orduña monastery is pending before a court in the Basque city of Bilbao.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.