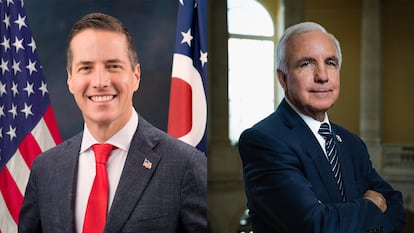

Bernie Moreno and Carlos Giménez, the Republican lawmakers leading the campaign against Petro in Washington

The senator of Colombian descent and the representative from Florida are the most visible faces of the effort to undermine Colombia’s political left ahead of presidential elections

It is October 21, 2025. Tensions between the United States and Colombia are running high: two days earlier, Donald Trump accused Gustavo Petro of being a “drug trafficking leader.” All of Colombia fears a harsh retaliation in the form of tariffs, a blow that would affect thousands of businesses and an entire economy dependent on exports to the United States. But Bernie Moreno, a Republican senator from Ohio of Colombian descent, dismisses this possibility. In an interview with Fox News, he says that the country should not fear a trade war because the sanctions will be directed at Petro and his inner circle. He reiterates this a day later Wednesday in the Colombian media: Petro, “the root of the problem,” will be added to the OFAC (Office of Foreign Assets Control) list.

Two days later, on Friday, October 24, the promise is fulfilled. Petro, two of his relatives, and the Minister of the Interior, Armando Benedetti, are added by the U.S. Treasury Department to a list that also includes terrorists, mobsters and drug traffickers. “Indeed, the threat was carried out,” said the Colombian president. Moreno responded: “FAFO,” an acronym for “Fuck Around and Find Out.”

Moreno and other Republican lawmakers, such as Carlos Giménez, a representative for Florida, have become the public faces of a campaign against Petro in Washington in recent weeks. Their statements have garnered significant media headlines: they have commented on everything from the decertification of Colombia to the military attacks against alleged drug-trafficking boats in the Caribbean and the Pacific, and even the legal case against former President Álvaro Uribe Vélez. An academic source familiar with U.S.-Colombia relations asserts that the Republicans have a strong affinity and a direct line to several Colombian right-wing politicians, including former president Uribe. The purpose is clear: to ensure the left loses in the presidential elections next year.

Sergio Guzmán, director of the consulting firm Colombia Risk, explains that Moreno, Giménez, and María Elvira Salazar (also a representative from Florida) “are very influential people within the Republican Party and its far-right wing,” which includes a large part of Trumpism. “President Trump gives each member of Congress prominence because of the issues they address. Furthermore, he wants to keep them happy because they are officials from very important states like Florida and Ohio,” he notes in an exchange of messages. For this reason, the statements made by these members of Congress have had repercussions in the White House.

María Claudia Lacouture, president of the Colombian-American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham), who has had numerous contacts with the Republican wing of the U.S. Congress in recent months, says: “It’s not random. There has been a collaborative effort since January [the first time Trump threatened Colombia with tariffs] to convey to Washington the need for a good relationship. They have determined that there is much more to Colombia than the government.” And she notes in a phone conversation: “Bernie Moreno has been crucial in this process and has championed the cause of defending Colombians.”

Last week, the senator from Ohio accused Petro, during a hearing of the U.S. Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control, of abetting “Hezbollah’s activity in Colombia” and of showing sympathy for Hamas. Both groups, the Lebanese Hezbollah and the Palestinian Hamas, have been designated as terrorist organizations by Washington. In another public relations move, Moreno sent a letter to the State Department, which is headed by Marco Rubio, requesting that it designate three Colombian armed groups as terrorist organizations: the General Staff of Blocs and Fronts (EMBF), the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (or Gulf Clan), and the Conquerors of the Sierra Nevada Self-Defense Forces (or Los Pachencas). These are three organizations with which Petro’s government is negotiating peace at various levels.

Petro is well aware of Moreno’s influence in high-level Washington circles. “Trump has been encouraged by U.S. Senator Bernie Moreno to clash with us. This isn’t Trump’s doing. [...] Moreno is trying to smear us, telling [Trump] that I’m a drug trafficker,” the president said during a televised cabinet meeting. According to him, this fierce opposition stems from the American politician’s ties to Colombia’s right wing. Petro accuses Roberto Moreno, Bernie’s brother and president of the construction company Amarilo, of having ties to an alleged money laundering case that supposedly benefited former conservative president Andrés Pastrana, under whose administration another brother, Luis Alberto, served as a minister.

The president and the senator met in August, during Moreno’s visit to Colombia, to discuss security cooperation and bilateral trade. “It went well,” the senator said at the time about the meeting. “We don’t have to agree on everything.” But it wasn’t enough to smooth things over.

Close ties to Uribe’s movement

The Colombian right’s good relationship with Republicans is also evident in the case of Representative Carlos Giménez, one of the most vocal U.S. congressmen in favor of Uribe’s political movement. He has frequently alluded to the former president in posts on the social media platform X. “I am happy about the news. I believe the conviction was unjust, as proven by this decision, which has overturned the conviction. I congratulate former President Uribe on his victory in the courts and hope to see him as soon as possible,” he said when Uribe was acquitted on appeal in a case against him for witness tampering, which he described as “political persecution”—the same expression used by U.S. State Secretary Rubio.

In his most recent publications about Colombia, Giménez questioned the selection of Iván Cepeda as the left’s presidential candidate. “I doubt that Colombians want to live in a country like the murderous dictatorship in Cuba, which has forced its people to live in abject poverty, without rights or freedoms. May God protect Colombia from the communist cancer!” he declared.

According to the analyst Guzmán, Giménez “is very involved in domestic politics and has an explicit interest in ensuring that no leftist remains in Colombia.” The country, the expert says, is central to the interests of his own voters. In his district, Florida’s 28th, which includes Miami-Dade County, seven out of ten residents are of Hispanic origin. In an interview with Semana magazine, Giménez mocked Petro for claiming to be fighting drug trafficking. “Seizing 2,700 tons of cocaine makes us the government that has seized the most cocaine in the history of the world,” the president responded.

During the most recent clash between Petro and Trump, many Colombian opposition politicians publicly declared their support for the U.S. leader, a figure many analysts believe will play a role in the 2026 elections, as he already did in Ecuador, Canada and Argentina. The pre-candidate María Fernanda Cabal, who is part of Uribe’s movement, asserted that “time has proven her right” after having supported Trump since his first presidency. Meanwhile, the far-right pre-candidate Abelardo de la Espriella went so far as to claim that if he became president of Colombia, he would extradite Petro if Trump requested it (even though Petro has not been found guilty of any crime to date). The “Trump effect” on the upcoming elections remains uncertain: more than 60% of Colombians have an unfavorable view of the American president, according to the polling firm Invamer. For now, it Trump’s his allies in Congress who are leading the effort from Washington to bring the right wing back to power in Colombia.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.