An intact 80-million-year-old fossil is the ‘Rosetta Stone’ that promises to decipher bird evolution

A new study reconstructs the skull and brain of ‘Navaornis hestiae,’ a species positioned at the crossroads of the evolutionary transition from ancient, dinosaur-like birds to modern avian species

In the evolutionary history of birds, there is a 70-million-year gap filled with questions. During this time, all the modern bird groups we know today emerged, but science has yet to fully explain how the transition from the ancient, more dinosaur-like birds to modern birds occurred. Now, an analysis of a fossil with an unprecedented degree of preservation — belonging to a previously unknown bird species that lived in what is now Brazil 80 million years ago — could help illuminate how this process occurred. The discovery is being hailed as a “Rosetta Stone” for the study of bird evolution, as it may unlock many of the mysteries surrounding their evolution. The research findings were published in Nature last Wednesday.

Guillermo Navalón, a paleobiologist from Madrid at the University of Cambridge, is one of the lead authors of the study, alongside Argentine researcher Luis M. Chiappe. He was in charge of digitally reconstructing the fossil using a non-invasive process and was able to reveal the life appearance of Navaronis hestiae, named after Brazilian paleontologist William Nava, who discovered it in 2016. “This fossil is so unique that it answers many frustrations that scientists have had in bird research for a long time,” explains Navalón.

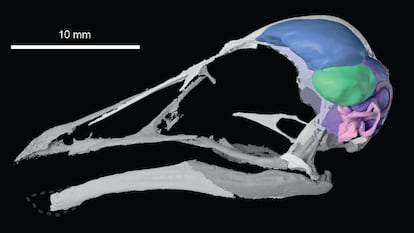

What makes this discovery so remarkable is that all previous fossils of extinct birds from the Enantiornithes group were found flattened, like a pancake, due to their delicate, hollow bones, which made preservation difficult. In contrast, Navaronis is nearly intact. This allowed scientists to reconstruct its skull and brain in three dimensions. While the brain tissue itself didn’t survive, the skull did, and since these animals — like humans — had bones closely surrounding the brain, researchers could examine the internal cavities. This allowed them to create a mold and replicate the soft tissue that would have been inside.

Understanding the brain structure of these ancient birds offers significant insight into their evolution and behavior. “We used a metaphor, perhaps a bit pretentious: the Navaornis is a Rosetta Stone. Just as that stone allowed us to understand hieroglyphics, this helps us understand how birds evolved. We have two evolutionary points — ancient birds and modern birds — and suddenly a fossil appears that is in the middle of that process and tells us what could have happened there,” explains Navalón.

So, what happened in this transitional period? A gradual evolution. By the time Navaronis appeared, there was already a mix of ancient and modern traits. “It has very advanced features that we thought were exclusive to contemporary birds,” Navalón explains. For instance, its brain is no longer tubular and elongated, as seen in ancient birds, but has become more globular, with a spinal cord that arches downward, similar to humans. “It is one of the most advanced characteristics that we identified,” says the researcher. The skull of Navaronis is particularly notable for being completely toothless and possessing a structure similar to that of modern birds, despite belonging to an older evolutionary branch.

The study also identified features of early birds, such as the cerebellum. In modern birds, the cerebellum is often bulbous, but in Navaronis, it is completely flat, resembling more primitive lineages. The cerebellum plays a crucial role in flight, as it is particularly active in contemporary birds during flight, which piqued scientists’ curiosity. How did this ancient species control flight? While some answers remain elusive, researchers are exploring the possibility that Navaronis had a different flight control mechanism. Additionally, the encephalon — the part of the brain responsible for higher cognitive functions — was of intermediate length in Navaronis, prompting speculation on how the animal moved and behaved.

Very complex animals

Studying the new fossil presents significant challenges due to the limited comparative data available. “We still don’t fully understand birds today and how changes in various parts of their brains relate to cognitive abilities,” Navalón says. Birds have very complex behaviors, making it difficult to study their evolution. Some species migrate thousands of miles using a range of navigation cues, such as visual landmarks, the Earth’s magnetic field, the sun and stars, and even scents. Other birds, like crows and parrots, use tools to acquire food and can even imitate human speech. How these behaviors are controlled neurologically remains a mystery in many cases.

Matteo Fabbri, an evolutionary biologist at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved in the study, commented: “These findings are a paradigm shift in evolutionary models, as this new Cretaceous bird species displays a puzzling set of morphological traits that connects modern birds to those of the early Mesozoic dating back more than 200 million years. Navaornis illustrates that the skeletal features of modern birds did not appear all at once, but in a mosaic fashion and gradually.”

The same holds true for their brain evolution. In other words, the transition from ancient to modern birds was a complex, non-linear process, with modern traits developing step by step, Fabbri explains.

Jesús Marugán, a vertebrate paleobiologist and researcher at the Autonomous University of Madrid, believes this new discovery not only advances our understanding of avian evolution but also opens up “a new paradigm.” “Special mention must be made of the digital dimension of this research. The fact that we can extract data from a fossil in a non-invasive way is a huge step forward,” he says. The techniques used in the study enable researchers to compare the morphology of different birds throughout Earth’s history with millimeter-level precision, all without physically manipulating the fossils.

Fabbri believes that the discovery is “a milestone that pushes the field of bird evolution forward, after more than two decades of waiting to find the right fossils.” While it is difficult to predict what other significant finds might emerge from the same site where Navaronis was discovered, the scientists involved are confident that this marks the beginning of a wave of revolutionary discoveries in the field.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.