Alejandro Gertz: Mexico’s attorney general becomes an ambassador at 86

The veteran politician resigns from the office two years before the end of his term, leaving Claudia Sheinbaum free to complete her security cabinet

Alejandro Gertz Manero, one of the veteran figures of Mexican politics, has stepped down as attorney general but, at 86, he is not retiring from public life. In his resignation letter, he said that he will become an ambassador “to a friendly country.” His departure had been widely rumored before, as had his health issues, but it was only on November 27 that he finally stepped aside.

Gertz waited until 5:15 p.m. to submit his resignation, after hours of chaos in the Senate. His departure clears the way for Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum to complete her security cabinet. Until now, Gertz had been the only member not appointed by the president.

Gertz became Mexico’s first attorney general in January 2019, nominated by then-president Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Previously, the institution had been called the Procuraduría. Although it may seem like a cosmetic change, it was actually a deep constitutional reform designed to give the office autonomy from the executive branch. From then on, the attorney general would serve a nine-year term, independent of presidential terms, meaning they could no longer be removed at the whim of a new president. Gertz, who was 79 when he assumed the office, was therefore supposed to serve until the age of 88. He did not make it that far.

However, he wielded a power that could become a weapon: institutional independence. Critics argue that Gertz used his enormous influence to settle personal vendettas and protect alleged business interests. While his job was to defend the Mexican people, in the eyes of many he was a self-serving attorney general.

Gertz’s appointment as attorney general in 2019 marked the return of a political survivor to public life. Born in Mexico City into a wealthy family with a background in the fine arts, he began his public career immediately after earning his law degree in 1961, during the final years of president Adolfo López Mateos’ Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) administration. In his early years, he combined work as a bureaucrat with roles as an entrepreneur, teacher, researcher, and writer — he is credited with authoring around a dozen historical and biographical books, according to his résumé.

In just over a decade, he rose from minor government positions — assistant, private secretary, legal adviser — to become Mexico’s first anti-drug czar under president Luis Echeverría in 1975. His office was officially called the National Coordination of the Campaign Against Drug Trafficking. Unofficially, the “campaign” became known as Operation Condor and marked the beginning of Mexico’s punitive approach to the drug war, which has fueled the country’s ongoing crisis of violence, disappearances, and forced displacement.

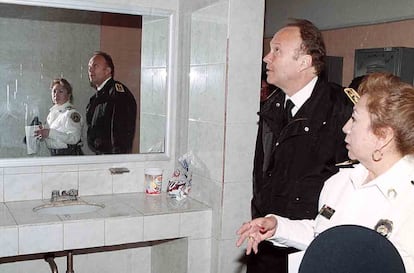

In 1998, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, founder of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), appointed Gertz as secretary of public security for Mexico City. Cárdenas became the first opposition politician to win the capital through a democratic vote. Was Gertz — a bureaucrat empowered for decades by the PRI — truly turning left with his appointment, or was it simply a pragmatic shift by a man adept at navigating the theater of politics? A lover of the dramatic, Gertz — after all — was the son of a fiction writer, Mercedes Manero, and had founded the National Association of Theater Producers in 1975.

Gertz served in Cárdenas’ government for two years. In 2000, he became the federal secretary of public security under Vicente Fox, a charismatic businessman from the conservative National Action Party (PAN). From this position, Gertz witnessed Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, head of the Sinaloa Cartel, escape for the first time — he would escape again — from a supposedly maximum-security prison in Jalisco in 2001, hidden inside a laundry cart. Guzmán would not be recaptured for another 13 years. Despite this scandal, Gertz remained in office until 2004, when he resigned to retire at the age of 65.

Gertz had no financial concerns. The grandson of a German businessman, Cornelius Gertz, the lawyer possessed a fortune that allowed him, in the years following his retirement, to acquire four homes in Spain worth 113 million pesos (more than $6 million), according to an investigation by this newspaper. He also bought an apartment in New York and another in Santa Monica, California, valued at $3.5 million, according to Univisión. That does not include the 122 luxury vehicles he purchased for 110 million pesos ($6 million), according to an accusation by the Financial Intelligence Unit (UIF) reported by El Universal. Gertz has always denied any irregularities in his immense wealth, the size of which he did not disclose to the Ministry of Public Administration, nor did he reveal any potential conflicts of interest.

In 2009, Gertz made a largely symbolic return to the political stage as a federal deputy for Movimiento Ciudadano (Citizens’ Movement), a young leftist party. During the three years he held the seat, he submitted 14 reform initiatives, none of which succeeded, and he was absent for more than half of the votes.

López Obrador’s rise to government following the 2018 election marked yet another return of Gertz to politics, this time with a level of power he had never held during his previous six decades as a public servant. The architect of his alignment with the Obrador administration and his subsequent appointment as attorney general was the influential Julio Scherer Ibarra, who served as legal adviser to the presidency. Initially allies at the start of the presidential term, their dramatic falling out in 2021 cast doubt on the impartiality of law enforcement and criminal prosecution under Gertz at the Federal Attorney General’s Office (FGR).

The most scandalous case involved his former sister-in-law, Laura Morán, and her daughter, Alejandra Cuevas, whom Gertz reported to the Mexico City Attorney General’s Office over the death of his brother Federico. Gertz accused both of homicide for allegedly neglecting his relative’s health. The capital’s prosecutor closed the case in 2016 due to lack of evidence. However, it was reopened in 2020, after Gertz took charge of the FGR. Immediately, Alejandra Cuevas was detained and imprisoned, where she remained for a year and a half until the Supreme Court ordered her release.

Beyond the cases where Gertz may have had a personal interest, it is undeniable that he was a loyal operative who understood López Obrador’s priorities and, in line with those winds, directed the FGR. There are several examples. When the U.S. government arrested General Salvador Cienfuegos, former secretary of defense, on drug trafficking charges, the Mexican president was concerned about the damage such accusations could do to the Armed Forces’ image. Cienfuegos was returned to Mexico, and shortly afterward the FGR announced that no legal action would be taken against him due to lack of evidence. Not only that: Gertz threatened to file international complaints against the U.S. investigators who dared to accuse the general.

López Obrador repeatedly said that he prefers that those accused of corruption return what they stole rather than spend their lives in prison. The attorney general listened to the president’s peculiar conception of justice and, based on it, pursued through the FGR the multimillion-dollar Pemex frauds and the Odebrecht bribery cases that marked Enrique Peña Nieto’s term, such as those involving Alonso Ancira and Emilio Lozoya.

During Gertz’s tenure, the FGR also closed the case on electoral crimes against Pío López Obrador, López Obrador’s brother, and pursued 31 Conacyt scientists following accusations from the president. This was because Gertz showed far less leniency toward López Obrador’s opponents, such as Rosario Robles, a former friend and collaborator of the president who later aligned with the PRI. At the FGR’s request, Robles was imprisoned — without a sentence — for three years for the multimillion-dollar embezzlements of the “Master Scam” during Peña Nieto’s government. Gertz pressured her to implicate former finance secretary Luis Videgaray in the corruption schemes, but did not achieve his objective.

Claudia Sheinbaum’s rise to power left Gertz out of place. Although he made gestures toward the new president’s government and toward Omar García Harfuch, the powerful security czar, it was not enough to secure his position. For weeks, reports circulated that officials in the National Palace were pressuring the attorney general to step down from the FGR, since, according to Article 102 of the Constitution, the president can only remove him for serious reasons. The other option was the long-discussed reform of the Attorney General’s Office. Sheinbaum carried out López Obrador’s flagship plan to reshape the judicial system, but experts all agreed: without changing how the Attorney General’s Office functioned, impunity in the country — hovering around 95% — would not improve.

Gertz was useful to Sheinbaum in addressing some of the early crises of her government, such as the discovery of the Teuchitlán ranch, the forced recruitment center of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, where he appeared publicly to deny that it was an extermination site, as searcher collectives had claimed.

However, Sheinbam also criticized some of his actions. This week, for example, a scandal erupted over Miss Universe and its powerful president, Raúl Rocha. The businessman had an outstanding arrest warrant and had been under investigation by the FGR since 2024. Members of the Attorney General’s Office were also involved in this investigation. In response to the snowballing situation, Sheinbaum asked Gertz to clarify the matter. Additionally, just hours before the attorney general’s resignation on Thursday, the president — who had not announced his departure — stated: “We need much greater coordination between the state Attorney General’s Offices and the FGR.”

Critics argue that Gertz squandered the nascent independence of the FGR, failing to steer a country riddled with impunity toward genuine law enforcement. That task will now fall to a Sheinbaum ally, the final link in the chain.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

More information

Archived In

Últimas noticias

Taylor Swift reveals obsessions, strengths and fears in new documentary: ‘I don’t want to be tracked like an animal, I’ve just felt very hunted lately’

Democrats release new photos from the Epstein files showing Donald Trump surrounded by women

Fugitive Natalio Grueso: In hiding with a glass of wine on an island in the Algarve

Ukraine trains civilians and journalists to survive under drone attacks

Most viewed

- Liset Menéndez de la Prida, neuroscientist: ‘It’s not normal to constantly seek pleasure; it’s important to be bored, to be calm’

- Belle da Costa, the woman who concealed her origins in 1905 and ended up running New York’s most legendary library

- A mountaineer, accused of manslaughter for the death of his partner during a climb: He silenced his phone and refused a helicopter rescue

- Trump’s new restrictions leave no migrant safe: ‘Being a legal resident in the US is being a second-class citizen’

- The fall of a prolific science journal exposes the billion-dollar profits of scientific publishing