A ‘war on drugs’ for regime change: Trump hits Maduro with gunboat diplomacy

The plan to hasten the Venezuelan leader’s downfall with a naval deployment in the Caribbean and a campaign of extrajudicial attacks on alleged drug boats has raised questions about what could come next

Ten warships in total, including three destroyers, an amphibious assault ship, a missile cruiser, and a nuclear-powered submarine, along with around 10,000 troops. The U.S. Navy deployment, ordered in August by Donald Trump in the area under the U.S. Southern Command’s influence, is almost unprecedented in the Caribbean and faces an equally unusual adversary: Venezuelan drug cartels.

A couple of weeks ago, the U.S. president informed Congress — without allowing for debate — that the country has entered into a war against drug cartels. So far, the reported casualties are modest compared to what such a show of force — mobilizing 14% of the U.S. Navy deployed worldwide — might suggest: four boats allegedly sent by drug cartels, which Washington accuses of drug trafficking, were destroyed in separate extrajudicial operations, with authorities offering no evidence beyond videos showing the moments when the vessels were blown up. At least 21 people have been killed in these operations, four of whom Bogotá claims as Colombian citizens.

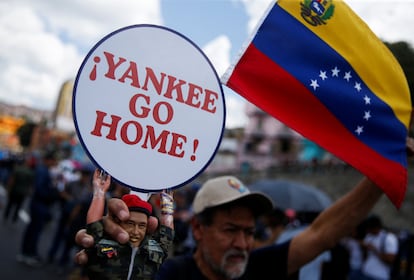

Trump’s offensive in the Caribbean has raised tensions in the region and fueled suspicions that this is about more than just reviving the drug war that once defined Washington’s policy in Latin America. “This isn’t about ending drug trafficking, but rather about bringing about a change of regime — a deeply corrupt and criminal regime — and making sure the move costs Washington as little as possible,” Christopher Sabatini, senior fellow for Latin America at Chatham House, explained in a telephone conversation on Friday.

Sabatini described the White House strategy as “gunboat diplomacy.” The goal, he explained, is “to intimidate the officials and military surrounding [Venezuelan President Nicolás] Maduro into letting him fall. It involves abandoning the same costly peaceful processes, that — it should be noted — earned [opposition leader] María Corina Machado the Nobel Peace Prize.”

Juan González, the Biden administration’s Latin America adviser, agreed with that assessment last week. “The deployment is vastly disproportionate to any real counter-narcotics mission. So this really looks, walks and talks like a regime change preparation,” he told CNN.

Second phase

The first phase of that offensive consists of the four extrajudicial military operations that Trump and his secretary of defense, Pete Hegseth, announced on social media.

For Sabatini, they are “worrying” for three reasons: “They expand the president’s executive power by inventing a new threat — narco‑terrorism — that requires an armed response; they ignore due process by blowing up boats without providing evidence of the identity of the crew or the cargo; and they exaggerate Venezuela’s role in the flow of drugs to the United States, since there is no evidence fentanyl is produced there and, according to official statistics, only about 5% of cocaine comes from Venezuela,” said the expert, who added that the destroyed boats “do not have the range” to reach the U.S. coast.

“They are probably heading to an intermediate point. Which one? We don’t know,” he said. Those uncertainties have not stopped the narrative promoted by Trump — who in February included several cartels, among them the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua, on the State Department’s list of “terrorist organizations” as a precursor to declaring war on them — from spreading the claim in recent days that each of those boats carried enough drugs to kill “25,000 or 50,000 Americans.”

“There’s a lot of theater in these attacks, and in the military deployment — even a nuclear submarine!” said Moisés Naím, a distinguished fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for Peace and one of the most influential Venezuelans in Washington. “It’s like a staged scene, a context that serves to justify subsequent actions.”

Last Sunday, Trump himself admitted that the operation against alleged drug trafficking would enter “phase two,” arguing that the strikes had stopped boats carrying drugs. “We’ll look at what phase two is,” he said, later adding, for the sake of clarification, that it would continue on land.

“It’s impossible to know what form [this operation] will take. It may focus on dismantling criminal networks and sites in Venezuela — ports or airports involved in drug trafficking,” said Sabatini.

“It won’t be an armed invasion with thousands of soldiers, as some might wish,” added Naím. “It will be surgical, selective, precise, and technological. I just hope that Machado’s Nobel Prize makes [Trump and his team] rethink their approach.”

Venezuelan opposition leader Machado won the Nobel Peace Prize for “her tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela.” She led a movement to collect the paper voter tallies from the 2024 election, which allegedly showed that the opposition had won the vote, contrary to Maduro’s claims — allegations accepted by most of the international community.

In an inteview with EL PAÍS on Friday following the Nobel announcement, she said: “We are facing the real possibility that Venezuela will truly free itself and move toward a transition that will be orderly, because 90% of the population wants the same thing. Don’t tell us this could be Libya, Afghanistan, or Iraq — this has nothing to do with those cases,” she said, referring to other disastrous U.S. interventions abroad; a pattern that Trump promised during his campaign he would not repeat.

But experts consulted in Washington are less certain that there will be an orderly democratic trainsition. There is also the widespread belief that the Trump administration is trying to finish what it started in 2019.

“And it’s being carried out by almost the same actors. Besides the president, there’s Marco Rubio,” warned Alexander Main, director of international relations at the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Back in 2019, Rubio was a senator able to whisper in Trump’s ear about Latin America. Today, he has become one of the most powerful figures in the White House, serving both as secretary of state and national security adviser. “The two were at odds during the 2016 campaign, but then reached a compromise: Rubio would help him mobilize Florida Republicans in exchange for support for his vision for [what in Washington is called] the Western Hemisphere,” said Main.

During Trump’s first administration, pressure on Venezuela came first through sanctions, then with support for Juan Guaidó, in what Sabatini calls “that fanciful idea of setting up a legitimate parallel government.” “I think Trump is still embarrassed for having invited [Guaidó] to the 2019 State of the Union address,” he adds.

At the time, Washington’s calculation — that this would make the Chavista regime collapse like a house of cards — failed. Main fears that the lessons from that experience were not learned. “I think Rubio and Trump are once again confident that a brief military intervention will bring down Maduro, when the consequences of something like this are unpredictable. Most Venezuelans, even if they are fed up with their president, are not in favor of a U.S. intervention.”

Last week, Trump ordered, in another display of aggressive foreign policy that has produced uneven results in Gaza and Ukraine, the halt of all diplomatic contacts with Venezuela, after months in which Maduro — facing his most difficult days — tried unsuccessfully to appease Washington by offering dominant participation in the country’s oil and mineral resources, according to The New York Times on Friday. The Venezuelan president also promised to distance the country commercially from China, Russia, and Iran, his current partners, who had provided funds to mitigate the impact of international sanctions.

The White House rejected the proposal. Moreover, in August, it doubled the bounty to $50 million for any information leading to Maduro’s capture, whom Washington considers the leader of a narco-state.

The order to cut diplomatic ties was directed mainly at Richard Grenell, Trump’s envoy in the region, who has some rapport with Jorge Rodríguez, Maduro’s top political operator. According to sources close to the Chavista leadership, the Venezuelan president was not as submissive as Washington would like to believe. In any case, the diplomatic channel is broken, except for the part in which Venezuela continues to receive flights returning deported migrants from the U.S. — about 10,000 since February.

On the streets of Caracas, accustomed to 25 years of Chavista uncertainty, the same doubts heard in Washington offices are echoed: no one knows what the extraordinary U.S. naval mobilization will bring. Or perhaps it’s that most people prefer not to comment on Machado’s Nobel Prize either. Better not to get into trouble.

Chavismo, for its part, is keeping the armed forces busy with almost weekly military exercises and has ordered all public institutions to decorate buildings and offices with Christmas ornaments, making it harder to define the mood in the country. Meanwhile, Maduro continues with his schedule of activities: inaugurating hospitals, signing a state of emergency decree for external unrest (granting him virtually unlimited powers that he already holds), and even receiving an honorary doctorate.

Around public buildings, corners have been reinforced with pairs of soldiers equipped with riot gear. Security rings around the Miraflores Palace, the presidential residence, have been expanded, and concrete barriers have been placed at the main access road to the capital from Maiquetía International Airport, to be moved if needed to “block the passage of enemies,” according to a soldier who spoke to Venezuelan state media.

The greatest military mobilization, however, is in the coastal areas. In Zulia and Sucre, which are home to key drug distribution hubs, fears of drone airstrikes are spreading. “There’s fear in the streets; people are expecting something,” said a resident of the Costa Oriental del Lago de Maracaibo. Panic buying (and stockpiling supplies) is the immediate reaction in Venezuela to the escalating political conflict — a habit dating back to years when long lines were the norm for basic provisions. Despite the tension, given the rising cost and economic decline, most Venezuelans for now are just concerned with daily survival.

Amid this scenario, there are no signs that Maduro is willing to relinquish power as part of negotiations, according to a source close to Chavismo. Resistance has become a way of life for a country that has endured devastating economic crises — almost like a nation at war — surviving as best it can under international sanctions. The U.S. fleet stationed in the Caribbean represents a real threat, but Maduro and his team appear prepared to push the situation to the limit, waiting to see if Trump dares to take a decisive step.

Time, however, is not entirely on Trump’s side, as critical voices about the U.S. president’s “gunboat diplomacy” grow in Washington. On Wednesday, the Senate narrowly rejected (48-51) an initiative by Democrats Adam Schiff and Tim Kaine that would have stopped Caribbean attacks before the 60-day deadline Trump set for himself under the War Powers Resolution of 1973. “So by early November, he would have to halt these military operations. If he decides to continue attacking ships without congressional authorization, then he would be breaking the law,” said Katherine Yon Ebright, from the Brennan Center for Justice, affiliated with New York University.

Ebright adds that the law also allows the president to request an additional 30 days to withdraw U.S. forces from the conflict zone — in other words, the waters that now host an extraordinary U.S. naval deployment, with few precedents in the recent history of the Caribbean.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.