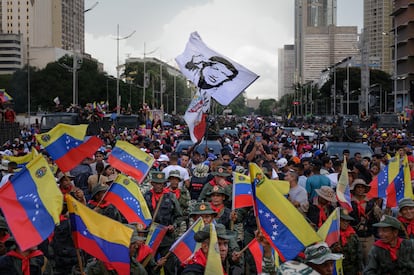

Maduro’s militiamen, rifle in hand, confront the United States: ‘Ready to defend Venezuela’

Chavismo is recruiting citizens with no military experience in the event of a possible war scenario

The scenes are astonishing. Men and women of all ages and physical conditions, zigzagging and crawling across the ground, rifles in hand. Quickly hiding behind mounds to avoid enemy fire. Aiming and firing with the greatest possible precision. Crossing a river, holding onto a rope. Perched on a tree, scanning the horizon with binoculars. The enemy seems to be at the door.

Venezuela is training its civilian population in combat tactics in case the United States — which has deployed forces in the Caribbean Sea and claims that Nicolás Maduro is an illegitimate president — takes the final step and attacks the country. Although a war scenario sounds impossible to many, the Venezuelan government has taken the signals from the White House very seriously, with the U.S. naval detachment having blown up at least five vessels that have left the Venezuelan coast allegedly on drug-smuggling runs and amid Donald Trump’s threats about striking targets on land.

Nervousness has soared among Maduro and his Praetorian Guard. Chavismo claims to have several million combatants at the ready — a figure impossible to verify — and hope to add even more with these crash-course exercises. More than one observer has raised an eyebrow. Facing them would be the U.S. military, with the greatest firepower in human history, one capable of subduing Iran in a single night with the most powerful non-nuclear bombs in existence. However, Maduro and the regime’s deputy, Diosdado Cabello, and even Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino, have shown no sign of submission in the face of Washington’s threat and often cite the war experiences of Vietnam and Afghanistan as examples that resistance is possible.

Most of those who have participated in the training are linked in one way or another to the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), the ruling party. They call it “a patriotic duty,” according to militia members interviewed by this newspaper. The training sessions have been televised. They have been carried out in the areas of Petare and Coche; and in La Guaira and Guarenas, near Caracas. The National Bolivarian Armed Forces have patrolled Caracas’s highways with their heaviest weapons. It has been stated that the training will include all of the country’s Communal Councils. Civilians are trained in close combat, weapons disassembly, shooting practice, physical exercises, and theoretical work.

“We’re not here to play games. We’re not here to revel. We’re preparing,” Padrino said at a recent event with civilian volunteers who were enlisting for combat on Caracas’s central Bolívar Avenue. “At the right time, the people would take up armed struggle, inch by inch, to defend the homeland, national honor, and national dignity.”

The atmosphere on the streets, however, is still far from conveying the imminence of an international military conflict to the population. It’s not easy to go to a poor neighborhood in Caracas and openly recruit volunteers to go to war. The ruling party is satisfied with the response of its militants, but the prevailing sentiment among the majority of the population regarding what is happening is one of distance and expectation. The decline in Chavismo’s mobilization capacity is being laid bare.

They primarily train what the government considers “social movements” (Chavista civil society). Alongside them is the Bolivarian Militia of Venezuela, a military component founded by the regime to which many civilians also belong. The so-called social movements are made up of groups like Futuro and Somos Venezuela; the street leaders of each community; the leaders of the UBCH (Bolívar-Chávez Battle Units); the most committed members of the Communal Councils; the armed collectives; the beneficiaries of the Local Supply and Production Committees (CLAP); and cultural groups aligned with the government.

Both bodies have served as a natural bridge between the concerns of the civic-military leadership governing Venezuela regarding threats to the nation and the potential interest of ordinary people in hearing them. Beneficiaries of government social programs, holders of the so-called Homeland Card, are currently being asked if they are willing to enlist for national defense.

Although they are in the minority, it is true that citizens emotionally disconnected from the government have also enlisted. A significant number of volunteers have come forward for these military training sessions, a result of the ruling party’s total control of the public message and the undeniable organization of its militants, but the overall response of the population is far from being overwhelming.

“In Venezuela, we don’t recruit people. We’ve put out calls,” explains Rubén, an activist from the Las Palmas neighborhood of Caracas, who declined to give his last name. “You call 100 people, 15 register. We keep track of them. In each area of the city, you recruit volunteers. When you come to see them, from area to area, you have a large group to work with.”

“Ready to defend the homeland from traitors, from sellouts, from those who want to violate the sovereignty of this country, which is sacred,” stated Lieutenant Sara, on active duty, who also did not want to give her full name, and who did not want to add anything else “because we don’t have to talk to the international press.”

Several militia members and volunteers involved in these activities declined to comment, stating that they needed permission from their superiors. “I wouldn’t go out into the streets shooting, not even if that were to happen,” murmured a resident of the Chapellín neighborhood, formally identified with Chavismo’s organizational and social programs, who preferred to remain anonymous. His story is a common one in the twists and turns of national society. “There are a lot of people who are working with the government out of necessity. You work with them, but nothing more. It’s all lip service. No one is going to go out and kill themselves with so many hardships that people in this country are experiencing.”

Maduro recently declared a so-called state of external commotion, a constitutional clause invoked for these types of situations, although it seems redundant in a context like Venezuela’s, where the government wields complete control. Some observers of Venezuelan politics have been concerned about this measure, which could serve to increase censorship, reduce the limited space enjoyed by the opposition, suspend constitutional guarantees, or militarize daily life in the country.

“What the United States wants is to get its hands on our oil, that’s clear,” says Carlos Jiménez, one of the many leaders of Chavismo’s social movements in the capital, based in the La Florida neighborhood. “And I say there is dignity here; what the United States government says is unacceptable. We have the blood of Bolívar; we are the people who liberated America. We may have differences in the local debate, but the country, Venezuela, comes before all that.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.