The watermelon: Painterly inspiration, political symbol and protest statement

Star of summer still lifes, the fruit has been used to symbolize carnal passions, racism and nationalism throughout art history

There are times when a simple gesture is capable of unleashing a gale of emotions, conjuring from a finite universe the promise of infinite pleasure. So it is every year when, after a long wait, we crack into the hard green shell of a watermelon, leaving its interior exposed.

Sight is the first sense overtaken by the striking red of its flesh. Then comes touch — our tongue jolted by its cold, wet nature, as ancient physicians once described it. And our hands too, as its sticky juice inevitably begins to run between our fingers. On the palate, it sparks a true celebration, and to top it off, watermelon takes on power in that invisible stomach we call memory. There, it becomes our summer version of Proust’s madeleine, and that first bite brings back memories of other bites — on the beach, by the pool, in the backyard. It reassures us of what we already know but still need it to confirm: summer is here.

This — and much more — is what The First Cut (after Robert Spear Dunning), a 2009 still life by Australian photographer Robyn Stacey, explores. The piece is part of her Empire Line series, and it’s no coincidence that the artist has chosen a watermelon as the central subject of the image — few foods appear as consistently in summer still lifes throughout art history. Yet, in contrast to the restraint of Stacey’s photograph, the presence of watermelon in still life painting has always carried a barely concealed sensuality. A clear example is the very work that inspired this contemporary version: Still Life of Fruit, Honeycomb and Knives (1867), by Robert Spear Dunning.

The scene seems to take place just a few minutes after Stacey’s image — when that timid first cut has unleashed the unruly desire that gluttony provokes. Gone are the precise slices with which our parents used to dissect watermelons every summer. Here, the diners have plunged in shamelessly, as if devouring it in wild, open-mouthed bites. In contrast to the neatly sliced, out-of-season orange and the pristine condition of the other summer fruits, the watermelon appears to embody everything that is pleasurable and uncontrollable about eating.

Sensuality evoked by the fruit appears in even starker contrast in compositions where the watermelon is accompanied by dry foods, as in Luis Egidio Meléndez’s Still Life with Watermelon, Pastries, Bread and Wine (1779) in which when seen alongside those other offerings, the watermelon emerges triumphant, drops of its juice appearing to be on the brink of falling off the canvas.

Indirectly, these representations have also been a rich source for botany throughout its history, as demonstrated by the studies of Susanne Renner, Harry Paris and Jules Janick, who have compiled hundred of images of the fruit in places as diverse as the tomb of Tutankhamun, the late medieval manuscript Tacuinum Sanitatis, and, of course, the still lifes and market scenes produced since the Renaissance—all to demonstrate a significant transformation in the shape, color, and likely even flavor of the watermelon over the centuries. A quick glance at Still Life with Fruit (1641) by Albert Eckhout is enough to reveal that the watermelon as we know it today is a kind of miracle — half nature, half human creation.

The fleshiness of the fruit’s pulp, and particularly its color, have made the watermelon an irresistible subject for artists from the 17th century to our present day. Current depictions are still imbued with its sensual connotations, as seen in Tsai Ming-liang’s film The Wayward Cloud (2005), in which the protagonists, faced with a terrible drought, are invited to quench their thirst with the watermelon’s juice. They inevitably go on to use it in satisfying other bodily needs.

The watermelon as political image

But beyond its powerful link to sensuality, watermelons have also been used in art with political and social undertones, drawing on elements as varied as its colors or the identity of its main producers.

On certain occasions, watermelons have served as a way to characterize (and stigmatize) a social group. Such is the case with the African diaspora in the United States. As Spanish writer Federico Kukso explains in his book Frutologías: Historía popular y cultural de las frutas (Fruitologies: Popular and Cultural History of Fruits), this peculiar connection arose in the 19th century, when enslaved African Americans were finally emancipated during the Civil War. One of their primary sources of income at the time was the cultivation and sale of foodstuffs, in particular, watermelons. So it was that the fruit came to characterize the stereotypical cliché of Black people in supposedly humorous images clearly created with the intention of denigrating them. The early days of advertising were awash in such depictions, with ads, postcards and theater bills, such as one preserved in the Library of Congress from approximately 1900, sucking all the juice out of the association.

Cinema, still in its early days, was not exempt from this regrettable trend. Films like A Watermelon Feast (1896) by William Kennedy Dickson and Watermelon Contest (1896) by James H. White likewise exploited the racist stereotype that Black people derived their greatest joy from watermelon-eating contests and parties, with the fruit taking center stage.

But while visual art has at times used the watermelon as a weapon against a marginalized group, it has also been reclaimed as a symbol of resistance and national pride. Its green, white and red was employed by a range of Mexican painters, who saw in it a love of country, associating the watermelon with the colors of the national flag.

Among them, Rufino Tamayo stands out for his sustained use of watermelon imagery, beginning in the late 1960s and ultimately turning it into an unmistakable emblem of 20th-century Mexican art.

Frida Kahlo’s Viva la vida (in English, Long Live Life; 1954) deserves special mention as a true pictorial testament created one week before she died, on which the artist inscribed the title of the piece next to her name on a slice of watermelon.

In another part of the world and for entirely different reasons, the watermelon’s shape and colors, including the black of its seeds, have provided an ingenious way of defending the Palestinian cause. At the end of the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel prohibited Palestinians from displaying national symbols like their flag in public, with the excuse that they were an incitement to terrorism.

In a response that continues to be employed to this day, the friendly fruit was used to circumvent that ban on the streets as well as in art, situating the watermelon firmly in the context of protest, e.g. Khaled Hourani’s This Is Not A Watermelon (2024) and Jordanian illustrator Sarah Hatahet’s Watermelon Resistance (2021).

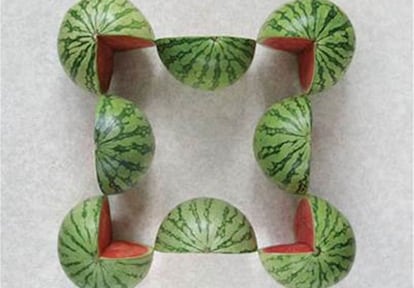

Still, the weight of tradition is heavy on the watermelon, which refuses to be shaken from its ornamental charm in the world of art. Its hypnotic colors, perfect geometry and inevitable associations with summer and sensuality often emerge in contemporary creations, such as those of Turkish artist Şakir Gökçebğ in Cuttemporary (2007), in which the fruits take on kaleidoscopic shapes that dazzle the eye and encourage us to prolong summer beyond reason, until we enjoy, already with a flush of nostalgia, the last watermelon of the season, consoling ourselves with the thought that, unlike summer romances, they will return next year.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.