‘Black history is a horror story’: Literature and horror films confront racism in the Trump era

Filmmaker Jordan Peele selects his favorite Black authors in ‘Out There Screaming,’ an anthology of stories. The book serves as the cultural industry’s spearhead against racial clichés

In mid-October, the American horror community — led by Stephen King — revealed its greatest fear to the world: the return of Donald Trump to the White House.

To help stop him, writers, filmmakers and other cultural agents organized an online event titled Scare Up The Vote, in favor of Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic Party’s candidate. Not by chance, some of the most prominent voices at this meeting were people of color: from Tananarive Due — a leading author of what is known as “Black horror” — to Stephen Graham Jones, an experimental writer and member of the Blackfeet Tribe.

Among the participants was also P. Djèlí Clark, a New Yorker of Trinidadian origin. A few days after Trump’s victory, he travelled to Barcelona for Festival 42, which is dedicated to fantasy literature. There, Clark endorsed one of the maxims of his colleague, Tananarive Due: “She always says that ‘Black history is a Black horror story.’ Inevitably, African-American authors have grown up under the influence of the Civil Rights Movement, along with a cultural heritage that’s the product of social oppression, from slavery to the present day. That’s reflected in the stories we tell and how we tell them,” he explains to EL PAÍS.

In Ring Shout (2020) — his most successful novel — Clark turns the second coming of the Ku Klux Klan into a dark fantasy. It centers on Black female soldiers fighting against an army of hooded monsters, who are on the loose after watching The Birth of a Nation (1915). “We cannot forget that it was the first film to be screened in the White House,” Clark points out. “Its popularity led to a wave of murderous racism throughout the United States.”

In D. W. Griffith’s film, the Ku Klux Klan saves a white woman, who is about to be raped by a freed slave (a white actor in blackface). The unfounded fear of the Black rapist led to a wave of lynchings across the country. In response, the Pan-Africanist historian W. E. B. Dubois would publish the post-apocalyptic story The Comet (1920), in which a white girl and a Black boy — the only survivors of a meteorite that destroys New York — unite across the racial barrier, until a white male savior appears to restore order.

“The historical context is important,” Clark emphasizes. “As I was writing Ring Shout, I couldn’t imagine that its publication would coincide with the police killing of George Floyd. I thought my little novel would serve as a reminder, but there’s no need to remind us of anything, because all that real terror that we Black people experienced is still just as present in the U.S. today. Did you see the thing about Black American citizens receiving anonymous messages on their phones threatening to send them back to pick cotton after Trump’s re-election? Lynching today continues to happen, with all the tools at its disposal. And that’s infinitely more terrifying than any story a writer like me can publish about the Ku Klux Klan,” Clark reflects.

P. Djèlí Clark is one of the 19 authors chosen by filmmaker Jordan Peele for an anthology of Black horror stories: Out There Screaming: An Anthology of New Black Horror (2023). The book includes stories by other essential contemporary authors, including Tananarive Due, Cadwell Turnbull, Nnedi Okorafor, Tochi Onyebuchi and N. K. Jemisin. In the preface, Peele writes that horror is “a way to work through your deepest pain and fear — but for Black people that isn’t possible, and for many decades wasn’t possible, without the stories being told in the first place.”

The director won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for Get Out (2017). He turned traditional horror narratives on their heads with Black characters. In the film, an elite group of privileged whites prolong their lives by kidnapping, auctioning off and transplanting their consciousnesses into the bodies of young Black people. Its release coincided with Trump replacing Barack Obama as president. “Get Out is a documentary,” its creator tweeted ironically.

Robin R. Means Coleman — an academic who specializes in the representation of the Black community in horror films — has made Peele’s filmography an object of study in her classes. “With Get Out, he went a step further. He questioned what cultural critic Rich Benjamin calls ‘white suburban utopias,’ those residential communities that have become bastions of security for white neoliberal people. Suddenly, those suburbs became dangerous, and the safe place was Black Brooklyn,” she explains to EL PAÍS in a video interview.

In 2019, Means Coleman produced the documentary Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror. She reminds the viewer that “although there’s now a renaissance of Black horror, there have been interesting creators for decades. We can go back to the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, with filmmakers like Oscar Micheaux or Spencer Williams. Or to people who marked an era, like William Crane with Blacula (1972), or Rusty Candieff, director of Tales from the Hood (1995).” The latter — a kind of Creepshow produced by Spike Lee — used humor and horror to issues such as institutional racism, gender violence, gang conflicts and police brutality. One particular episode dealt with events that took place in real life: the acquittal of four police officers for beating up taxi driver Rodney King, which would cause the worst race riots in the history of Los Angeles.

With Night of the Living Dead (1968) — filmed in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement — a turning point came. George A. Romero chose Duane Jones as the lead actor in the film because “he was the best actor who showed up on casting day.” For the first time in cinema, the Black man was neither the victim nor the danger, but rather the protector against the monsters. “As soon as filming was over — which took place in a town in Pennsylvania — Romero said that he put the film cans in his car to go to New York, and on the trip, he heard the news of Martin Luther King’s assassination on the radio. I’d like to think that, at that moment, he was aware of what he had intuitively filmed. It became an instant classic because of its ability to reflect the social turbulence that was taking place in the U.S. at that time,” Means Coleman reflects. That is, a new racial reality: peaceful marches had given way to riots to confront persecution and murder.

Now, even though Romero’s film has a Black hero, the protagonist still ends up getting shot by the white authorities and burned in a pile of zombies. It’s one of the great clichés of horror cinema: the Black man must die. Means Coleman is actually the co-author of a book entitled, precisely, The Black Guy Dies First (2023). In horror films, she analyzes, he’s the “sacrificial Black man,” always willing to give up his life for the white protagonist. A glaring example: Kubrick killing the only Black character in The Shining (played by Scatman Crothers) simply to cause a shock in the final stretch of the film. But in King’s novel — which the movie is based on — the character survives.

Another common trope is the “Magical Negro.” The Black man who — thanks to his paranormal perception and spells — helps the white man achieve his ends. Something that Whoopi Goldberg took to the extreme of parody in Ghost (1990).

“There are horror comedies that have played at dismantling these stereotypes, like Scary Movie (2000) or Meet the Blacks (2016),” Means Coleman acknowledges. “The [last girl to survive] is no longer always the white one, but there’s still a long way to go. The sacrificial Black character persists, not only in horror. When you see films like Civil War (2024) and they introduce this older Black character who isn’t going to be able to run away when danger presents itself, you already know that he’s going to sacrifice himself for the white character,” she notes.

Professor Kinitra Brooks — a specialist in Black cultural studies and author of a series of articles titled The Safe Negro Guide to Lovecraft Country (2020) — thinks that “many of these clichés come from white people, who have dominated the visual arts industry, undertaking a reading of Blackness. But these ideas have become outdated. In recent years, they’re being flipped around. Firstly, because white people are better versed. Secondly, because there are more and more Black voices expressing our reality: if it’s a Black person who speaks about magic, instead of something evil, it can be a connection with our ancestors, an instrument of power. And thirdly, the conversation has moved to another place: audiences today demand more sophisticated discourses,” Brooks comments via video conference.

Means Coleman emphasizes “there’s no cliché more harmful than systematically erasing the presence of Black people: it’s been the most effective way of silencing us historically.” But the change is beginning to be palpable. In 2023 — according to the website Blackhorrormovies.com and its creator, Mark H. Harris (co-author of The Black Guy Dies First) — “the number of Black roles in horror films and series has tripled since the release of Get Out in 2017.”

However, there’s still an unresolved issue in the industry: despite the numerous novels and stories published by Black authors, their works are rarely chosen to be adapted for the screen. “And, when it happens, many details are lost and few are privileged to reach large audiences. If they [alter] Stephen King, imagine [what they do to] works by racialized authors,” Means Coleman continues.

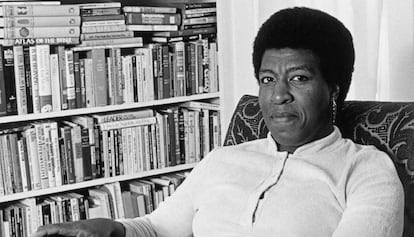

Fans of Octavia E. Butler, for example, were disappointed to find a hollow and reductionist vision of Black trauma in the recent miniseries adaptation of Kindred (1979), a landmark novel in which a Black writer accidentally travels back in time to meet her enslaved ancestors.

Black horror literature has always had a political role, as Kinitra Brooks reminds us. She refers precisely to other speculative fictional works by Octavia E. Butler: The Parable of the Sower (1993) and its sequel, The Parable of the Talents (1998). In this dystopia — published in the 1990s and set in the 1920s and 1930s — a Christian fundamentalist presidential candidate presents himself as the best solution for a United States ravaged by ecological disaster, structural racism and the collapse of capitalism. He brandishes a triumphalist slogan: “Make America Great Again.” Sound familiar?

“In those super dark books about the end of the world, Butler not only grasped the times, but also the subject matter. She saw that everything was going down the drain and gave us a guide to cope with it. Whenever things go bad, Black people always have it worse. My father always reminded me: ‘I was born in the 1950s and grew up in the 1960s: we’re going to be fine.’ We know what it means to be in the fight, even though there’s still a long way to go,” Brooks concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.