Meet the man who recorded the world’s first viral video

In 1991, George Holliday filmed LA police beating Rodney King, sparking deadly race riots

One of the first things George Holliday did when he bought his then cutting-edge Sony Handycam 8-millimeter video camera in early 1991 was to go into a bar in front of his house in north Los Angeles. It was there that he managed to capture some moments from the shooting of the celebrated scene from Terminator 2 when Arnold Schwarzenegger steals a biker’s clothing and rides off on his Harley Davidson.

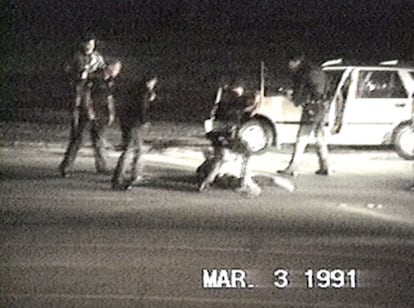

On March 3 of that year, using the same tape and in the same place, he recorded the savage beating by several police officers of an unarmed black man called Rodney King. The term might not have existed at the time, but this was the world’s first viral video, as well as an early example of citizen journalism, becoming a symbol of police brutality and sparking the worst race riots in US history in Los Angeles a quarter of a century ago.

Holliday says he was woken up around 1am by the sound of a helicopter. The police had been chasing King in his car at speeds of up to 160 kilometers an hour, and the chase ended in front of Holliday’s apartment. He went out on to his balcony to look, and when he saw police decided to record the scene. King was about 40 meters away, and the camera picked up the sound of the batons used by the officers to beat him for eight minutes as he lay on the ground. “I thought to myself: what did that guy do to deserve that?”

People have blamed me for the disturbances. What is on the tape caused them, not the tape George Holliday

He didn’t know what to do with his recording: this was a time before YouTube or Facebook. A few days later he went to a wedding, where he told guests about what had happened, but nobody considered it important. He then contacted his local police station, but officers would give him no information. Finally, he called local television station KTLA to ask whether there had been a police operation in his neighborhood. “During the conversation, the fact that I had recorded something came up and they asked if I would show them the tape,” remembers Holliday.

The same night, KTLA played the recording on its 10pm news program, attributing the footage to Holliday. “My phone blew up. Everybody wanted to interview me and get a copy of the tape,” he says, adding: “I had to disconnect the phone.” The next day he went back to KTLA to get his tape. “They told me it was a bigger story than they had thought and asked if they could hold onto the tape for a couple of days in return for $500.” He accepted. A few hours later, police officers turned up at KTLA and confiscated the tape. Fortunately, a copy had been made, which the television station kept.

Four white police officers were tried for the assault. On April 29, 1992, they were found not guilty by a white jury, even though the entire planet had seen, for the first time, video evidence. That afternoon, the worst violence in decades swept through Los Angeles, lasting six days, and during which more than 60 people died. “Some people have blamed me for the disturbances. What is on the tape caused the disturbances, not the tape itself,” says Holliday.

Holliday speaks fluent Spanish. His father, British, was a senior executive at the Shell oil company, while his mother was German. He was born in Canada and lived in Indonesia and London, but his father decided to retire in Buenos Aires, which is where Holliday grew up. He left in the late 1980s, looking to make his way in the world.

My phone blew up. Everybody wanted to interview me and get a copy of the tape George Holliday

“One day my son came home from school and said, ‘Dad, you are in a history book’,” says Holliday. The name Rodney King is still often used when a news program broadcasts the latest video of police brutality, nowadays filmed with smartphones. But Holliday says that for him, the most enduring aspect of the affair is that he features in a Trivial Pursuit question. He is still sometimes recognized in the street, a quarter of a century later, although he rarely gives interviews.

Now aged 57, he is a self-employed plumber, and still makes some money from selling the broadcast rights to the video of the beating of Rodney King. A few years ago his Sony camera was returned to him by the police, but the original tape remains in the hands of the FBI.

He says he never spoke to Rodney King about what happened that fateful night 25 years ago, but about a year after the riots, paying for gasoline in a garage, he heard a voice call his name. “Hey, George Holliday! Do you know who I am?” “I didn’t recognize him, I had only seen him in photographs with his face swollen.” It was Rodney King. “He said to me, ‘You saved my life.’ I didn’t know what to say. We shook hands and said goodbye.”

English version by Nick Lyne.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.