New research uncovers ‘father’ of the modern watermelon in war-torn area of Sudan

A study of Ancient Egyptian paintings and genetic analysis point to the Kordofan melon, a wild variety with a white flesh that is still grown in the region of Darfur

The poet Pablo Neruda neary ran out of metaphors in his praise of watermelons: “the green whale of summer,” “a treasure chest of water,” “the coolest of all the planets,” “the fruit of the tree of thirst.”

A slice of watermelon could also be viewed as a page out of a history book. The fruit’s name in Spanish, sandía, comes from the Arabic sindiyyah, meaning “from Sindh,” a region of Pakistan that the plant supposedly comes from, according to the Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy.

But that’s a false lead. New research suggests a much older and more complicated story involving the Egypt of the pharaohs and stretching all the way back to Nubian farmers who lived in modern-day Sudan more than 4,000 years ago.

A team led by the German botanist Susanne Renner has been tracking the origins of watermelons with the same zeal of European explorers who searched for the source of the Nile River four centuries ago. Renner and her colleagues have been analyzing the fruit’s oldest historical footprint: two drawings from Ancient Egypt that suggest Egyptians were already eating watermelon 4,360 years ago. The illustrations were found inside the graves of powerful individuals at the necropolises of Saqqara and Meir, and they depict something that looks like elongated watermelons served on trays.

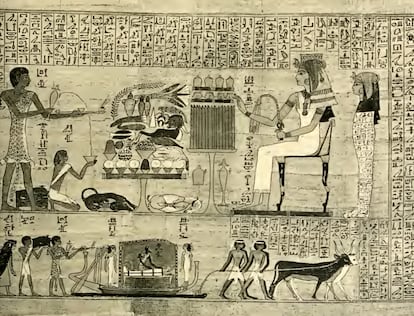

A third drawing found on the Papyrus of Kamara, a 3,000-year-old document, includes what appears to be a small, striped, spherical watermelon sitting on a table. Renner’s group believes it to be a Kordofan melon, an ancestral variety that is still grown in Darfur, a region of western Sudan that’s been ravaged by warfare for nearly two decades. The Kordofan melon is the main suspect of being the “father” of modern watermelons.

Renner, a former director of the Botanical Garden in the German city of Munich, holds that the Nubians, one of the oldest civilizations in the world, domesticated watermelons in the Darfur region and that the crop later moved north to reach Egypt. Both the sweet variety and the more bitter species from South Africa arrived in the Iberian Peninsula during Roman times, said Renner, who recently joined Washington University in Saint Louis, in the United States. “There is a recipe dating from the 4th century, written in Latin, to make jam out of the South African species,” she notes.

The researcher imagines the journey undertaken by watermelons across the globe from their starting point in modern-day Sudan. “We know that they reached North America soon after Christopher Columbus made his trip in 1492, and Brazil through the slave trade,” she says. The trade caravans along the Silk Route likely took the sweet watermelons to Asia during Roman or medieval times.

Renner’s team unsuccessfully tried to grow Kordofan melons at the Munich Botanical Garden. But Renner, 66, is planning a trip to the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, where she intends to taste a slice of the apparent progenitor of today’s watermelons.

The team’s research went beyond an analysis of the Egyptian drawings. Renner and her colleagues also sequenced the genomes of several kinds of modern watermelons, as well as the Kordofan melon, which has white flesh that is not bitter, unlike its relative the cucumber. The results, published in the scientific journal PNAS, show that the watermelon’s flesh became gradually redder and sweeter throughout the process of domestication.

The French biologist Guillaume Chomicki, co-author of the paper, underscores that the Kordofan melon is genetically more resistant to blight than modern watermelons. “Those genes were lost during domestication. This means that the genome of the Kordofan melon could potentially be used to develop disease-resistant watermelons,” notes Chomicki, a botanist at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom. Researchers are proposing the use of CRISPR, a revolutionary genome-editing technique that won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020.

Chomicki, 30, explains that watermelons suffer from a multitude of fungi and virus-related diseases. Besides fungicides, farmers use pesticides to prevent insects from spreading a virus from plant to plant. Watermelons genetically modified to imitate the blight resistance of the Kordofan melon “could significantly reduce the use of pesticides,” says Chomicki. China, at 61 million tons a year, is by far the world’s biggest producer, far outpacing Turkey (3.8 million), India (2.5 million) and Brazil (2.3 million). Spain is the world’s 14th producer at 1.2 million tons, according to data provided by the United Nations.

The southern region of Andalusia accounts for half of Spain’s entire production. Natalia Gutiérrez, a biologist at the Andalusian Institute for Research and Training in Agriculture, Fisheries, Food and Ecological Production (IFAPA), has worked on developing new varieties of the plant. Gutiérrez applauds the new research, which she did not take part in. She notes that crossing domesticated varieties with wild ones helps introduce new, interesting genes and makes the former more resistant.

Oscar Alejandro Pérez, 32, an agricultural engineer who was born in Bogotá (Colombia), did participate in the new genetic analyses of the various watermelon varieties. “We tend to think that species are units with their own unique identity, but both the Kordofan melon and the red-flesh watermelon that we eat today have some shared genes, they are united through time,” says Pérez, who works at the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens outside London.

Two years ago, the same team published a draft analysis of the DNA of a watermelon leaf allegedly found in the 1800s inside a 3,500-year-old sarcophagus near the Egyptian city of Luxor. The authors claimed at the time that this leaf proved there were already watermelons with a sweet, red flesh during the New Kingdom of Egypt. Guillaume Chomicki now admits that they were wrong. “When we drew up the draft, we still hadn’t carbon-dated the leaf. When we did, we realized that the leaf was not 3,500 years old, but instead from 1871, the year it arrived at [London’s] Kew Gardens.” What the team did find at Kew’s old botanical collections was two watermelon seeds that were 3,100 and 6,000 years old, respectively. Their future analysis will continue to reveal the journey around the world of Pablo Neruda’s “round, supreme and heavenly watermelon.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.