Shining a light on Nick Drake, the most mysterious singer-songwriter of the 20th century

A half-century after his death, an album of previously unreleased material reveals another side of the legendary artist

His fame arrived too late and in a most unexpected manner. It was the year 2000 and Volkswagen was presenting its new Golf Cabrio via an ad in which four men drive, top down under a full moon, listening to a song. The ad was a tremendous hit, with that previously unknown track being one of the reasons. It was Nick Drake’s Pink Moon, the eponymous song of his third and final album released in 1971. In 30 years, the LP had scarcely sold 6,000 copies. Three months after the commercial came out, that total had risen to 70,000.

So it was that the unfortunate Drake, who died in 1974 at age 26 in his parents’ house from an antidepressant overdose that may or may not have been accidental, became a cult artist decades after he left the Earth. His short life was quite eventful. A handful of Drake’s contemporaries, like Richard Thompson, John Cale and John Martyn admired his emotive voice, his particular way of playing the guitar and his melancholic melodies. After the singer-songwriter’s death, his legacy was treasured by other musicians like Lucinda Williams, Peter Buck of R.E.M., Paul Weller and Robert Smith, who says that his band’s name The Cure came from a Drake lyric (possibly a lie, but he did say it). 1990s indie rockers adored Drake, and his influence was palpable in the work of Belle and Sebastian, the Scottish group that in its early days sounded like nothing so much as a rebirth of the musician himself.

Today, Drake’s influence on thousands of artists is undeniable, but when he died, it barely made the news. “I think I found out through a friend. I don’t think it was published anywhere, besides an article in the local paper,” Paul de Rivaz, Drake’s college friend and owner of one of his rare recordings, told EL PAÍS.

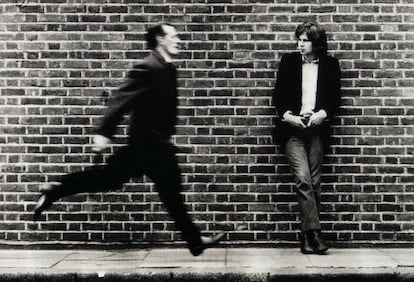

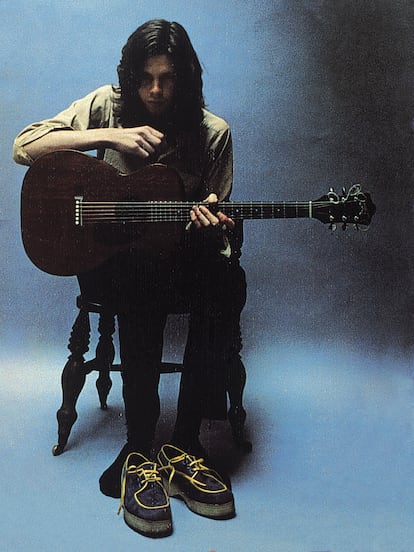

Indeed, the singer-songwriter had a nearly entirely underground career. He left behind three albums that had been met with disappointing sales: Five Leaves Left (1969), Bryter Layter (1971) and Pink Moon (1973). He only gave one interview and performed around 30 concerts. He never appeared on television or was ever filmed. He was very tall, thin, with a sad gaze — handsome in a melancholy way.

They say he was fragile, charming and extremely shy. He suffered from depression, often avoided physical contact and in his songs, appears as a solitary figure, as if an internal wall prevented him from establishing profound relationships. Drake presents himself as someone who would give anything to love and be loved. Today, our image of him has become rather mythical. Drake, an intangible being, a man too sensitive for this world.

In reality, he was very well loved. He was born in 1948 in Myanmar, then known as Burma, to an upper-middle-class British family. When the Asian country achieved its independence, they returned to England and Drake spent a happy childhood in the enormous family home in a town nearby Birmingham. In 1967, after finishing high school, he went to live for a year in southern France before starting his studies at the University of Cambridge. They say he was happy there as well. That year, he also set out on an adventure with his friend Richard Charkin, determined to drive across Morocco. The idea was to see the world and smoke joints. The climax of the trip was when he wound up at a café in Marrakech with the Rolling Stones, and Drake gave them an impromptu concert.

De Rivaz met Drake a few months after that trip, at Cambridge. “We set up sessions to listen to music, and he always brought his guitar and would play. Nick Drake was one of the nicest people I’ve ever met. You couldn’t imagine him shouting at someone or arguing. He had a sense of humor, but was chronically shy. He loved to play the guitar, sometimes his own compositions, sometimes covers,” de Rivaz recalls.

For decades, Drake’s heirs refused to put out any previously unreleased material. They didn’t want to publish anything that Drake wouldn’t have green-lit when he was still alive. That’s why his discography, save for a few exceptions, was long comprised of re-releases of his three official albums. But finally this month, The Making of Five Leaves Left was released, a four-album boxset with previously unheard material that looks to shed light on the process behind his first album, a 13-month project on which Drake worked with the producer Joe Boyd, sound engineer John Wood and his friend and arranger Robert Kirby. The idea was to humanize Drake’s angelic image a bit, to show that his work hadn’t fallen from the sky, but was rather the product of months of trial and error.

De Rivaz contributed the release’s most special component, a rehearsal recording that provides a new vision of Drake. He’s no longer an ethereal, timid being, but rather a musician with clear ideas and a splendid, personal guitarist — a role often forgotten by his admirers. “In 1968, Nick had a concert coming up and he was nervous because he’d never played his songs in public. I had a Grundig tape recorder and he asked me to to go with him to Rob Kirby’s room,” says de Rivaz. Kirby was going to play with Drake. “I arrived, plugged in the recorder and sat down. I didn’t say anything. Nearly everything was said by Nick. He’d play fragments of a song, stop, and say, ‘Now the flute would come in’ or ‘here, the violins’. Kirby barely intervened. Drake was in a good mood. I think he complained on the recording that he was a little hungover or something, but you couldn’t tell, he played amazingly,” says de Rivaz.

He hardly saw the musician again. That February 23, 1968 concert, in which Drake opened for Fairport Convention, was not recorded. De Rivaz never saw him live. “I didn’t have the chance. Besides, we drifted apart. After that afternoon, I saw him very little. He became more and more introverted, left college, and all I heard from him was his records. I think half of the people who bought his albums when he was alive knew him at Cambridge,” says de Rivaz, who nevertheless hung onto the fragile recording for almost half a century. “I resisted the temptation to erase it, because I always thought Nick had a great future ahead of him. I was wrong at the time, but the future can surprise you.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.