The Grateful Dead: A story of hippies, LSD and Lithuania’s iconic basketball uniforms

The Californian band, famous for its improvisational style and devoted Deadheads, played their final concert on July 9, 1995

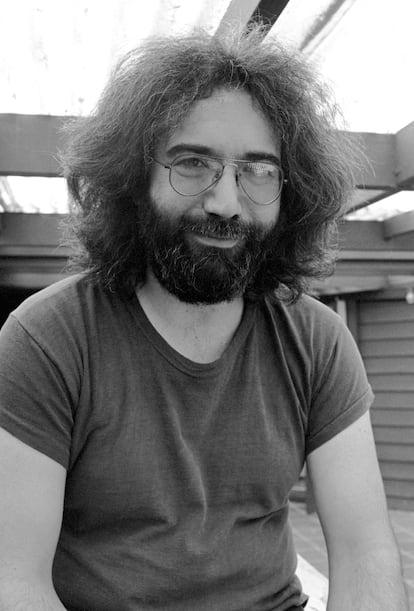

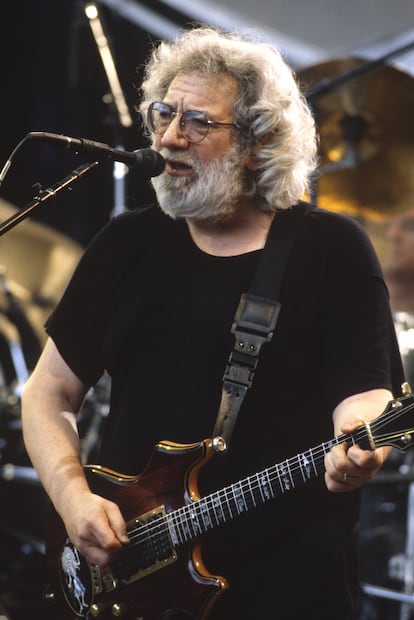

On July 9, 1995, The Grateful Dead played their final concert in Chicago. Just one month later, their leader, Jerry Garcia, passed away at 53 due to complications from diabetes. Despite being inactive during the latter half of that decade, they were the second highest-grossing band of the 1990s, surpassed only by the Rolling Stones.

This wasn’t the only record broken by the band, which was formed in Palo Alto, California, in 1965: it is estimated that over their 30-year career, they performed live for around 25 million people — making them the band with the largest live audience in rock history. Their biggest crowd came in 1973 at the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen festival, reportedly attended by 600,000 people. Just before the end of their career, they drew 90,000 fans to their historic concert with Bob Dylan in Vermont, also in the U.S.

They also hold the record for the most albums charted in their home country, being one of the major social and cultural phenomena that defined 20th-century North America. Closely tied to the birth of the 1960s counterculture, The Grateful Dead have been the subject of numerous essays and academic studies, and arguably possess the most loyal fanbase ever.

Sixty years after the band’s formation, the surviving members are now celebrating with a box set of no less than 60 CDs, titled Enjoying The Ride, which includes live recordings spanning their entire career. For those looking for a less ambitious introduction to their universe, the band’s label Warner has also just released their first greatest hits collection on a single vinyl record. Titled Greatest Hits, it includes nine tracks.

A unique band

Jerry Garcia (vocals and guitar), Bob Weir (guitar and vocals), Ron “Pigpen” McKernan (keyboards and harmonica), Phil Lesh (bass), and Bill Kreutzmann (drums) got their start playing bars in the San Francisco Bay Area under the name The Warlocks — until someone told them another band was already using that name. They then chose to call themselves The Grateful Dead.

They honed their craft by playing five sets a day, five nights a week at a venue called In Room, and their first concert under their definitive name took place on December 4, 1965, as part of the Acid Tests organized by writer Ken Kesey. These were parties featuring live music and projections, linked to LSD consumption (which was still legal in California at the time), and are considered a landmark event marking the beginning of the hippie movement and psychedelic culture.

There, the members of Garcia’s band began developing a near-telepathic communication that evolved into a style based on improvisation — closer to jazz dynamics than the traditional language of rock. Two years later, they crossed paths with Big Brother and the Holding Company (Janis Joplin’s band) and poet Allen Ginsberg at a benefit event for the Hare Krishnas at their temple in San Francisco.

Another legendary performance took place in May 1968 at Columbia University in New York during the student protests against the Vietnam War, where they hid their equipment in the truck that delivered bread to the campus cafeterias. By the time the police realized what was happening, the band was already deep into a psychedelic jam session.

They weren’t as lucky in 1970, when, during another tour, law enforcement raided their hotel on Bourbon Street in New Orleans and arrested 19 people for drug possession.

Deadheads in a mythical North America

The trippy, improvisational psychedelia with which The Grateful Dead began planted the seeds for what would later become progressive rock (in fact, they started around the same time Pink Floyd was doing something quite similar in England). But their approach was freer. They never took the stage with a fixed setlist; instead, they let the songs flow, often weaving several together as part of their improvisations.

Generally, the songs that appeared on their albums had been tested live beforehand — a practice many bands have since adopted, from their disciples Phish to groups as seemingly different as Animal Collective or Swans. Yet, amidst their cosmic journeys, there was also something deeply rooted in their homeland. The band allowed influences from country, folk, and blues to surface, while playing with imagery and narratives connected to major American myths, especially in the lyrics written by their collaborator Robert Hunter. According to Denis McNally, the band’s biographer, they created in those lyrics “a hyper-American, non-literal tapestry — a psychedelic and kaleidoscopic weaving aimed at unraveling the national character of the United States.”

It’s here, for example, that Javier Vielba, leader of the Valladolid-based band Arizona Baby, identifies their greatest influence. “In 1970, with the albums Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, they chose a predominantly acoustic sound and vocal harmonies very close to the Laurel Canyon sound and groups like Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young — which I believe have been as influential as their more levitating and expansive side,” the musician explains.

However, the band’s manager and former music journalist José María Rey believes “the essence of the band lies in their previous studio album, Aoxomoxoa, from 1969” and shares a little-known anecdote: “On the back cover of that album appears the earliest known photo of Courtney Love, aged 6 or 7, since she was the daughter of one of the roadies.”

The leader of Arizona Baby also highlights “that philosophy of closeness with their followers, forming a big family.” In this regard, The Grateful Dead were unique and immensely important to many people. Over the course of the 2,300 concerts they performed, they cultivated a very special sense of community with their fans, who were popularly known as “Deadheads.” Many of them followed the band on tour for months or even entire years.

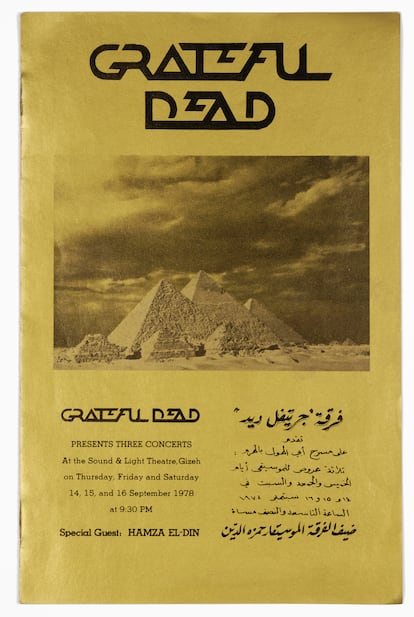

The band encouraged the creation of markets around the venues where they played. These were meeting places — which Deadheads called Shakedown Street after the band’s 1978 same-named album — where fans exchanged all kinds of objects and information. Among the many things found there, cassette tapes with recordings of their concerts had a special role — a practice that not only didn’t bother the band but was actually encouraged by them. They would even place boom microphones over the audience to improve the sound quality of these recordings.

As a result, The Grateful Dead probably hold another record: the band with the most circulating bootleg live recordings — many of which they officially released themselves. That spirit of freely sharing was part of their identity from the beginning, when they helped the local San Francisco community by providing food, shelter, and free medical care to those in need.

And one more record: some say they are the band that has given the most free concerts in music history.

“Despite the cynicism left by the hippie era, I believe the adventure of Garcia and The Grateful Dead is a great example of what hippie culture should have been: self-management alongside the record industry, communion between artists and audience, a community experience,” says Isabel Guerrero, music journalist at Rockdelux.

“I don’t think there’s any experience quite like that of the Deadheads — their subcultural and cultural impact has spanned multiple generations. They might be a very American phenomenon, but in the best sense of the word, by championing a free-spirited lifestlye, which now might sound naive but was exactly what every concert by the band represented. I think their vast bootlegs, recorded by fans, perfectly symbolize the essence of The Grateful Dead: embrace freedom, have fun, share.”

Their ideal of self-management was combined with a sharp business sense. By 1973, they had already created their own record label, Grateful Dead Records. Their career was tightly managed by Hal Kant, nicknamed “the czar.” Despite the band’s seemingly loose approach to allowing their concerts to be recorded and pirated tapes freely distributed, their manager and lawyer secured millions of dollars for the group through intellectual property and merchandising rights. They were also one of the first rock bands to own the masters of their recordings.

Regarding merchandising, they achieved several unique milestones. For example, the ice cream brand Ben & Jerry’s (whose owners, of course, were The Grateful Dead fans) created the first ice cream named after a rock musician: Cherry Garcia. Every November 23, they celebrate “Garcia Day” by giving away a Cherry Garcia ice cream to anyone who can prove they have that last name.

Even more surprising was their curious relationship with the Lithuanian basketball team at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Newly independent from the USSR, the Lithuanians lacked the funds to cover their trip to the games. Šarūnas Marčiulionis, one of their stars playing in the NBA, sought sponsorship, and the story attracted The Grateful Dead. They offered to pay for their trip to Barcelona and even designed their sportswear through their collaborator Greg Speirs. Those tie-dye style jerseys caused a sensation, especially after the Lithuanians won the bronze medal against the Unified Team (made up of former Soviet republics except the Baltic states). That Speirs-designed jersey became a powerful symbol of national pride in Lithuania.

Beyond the hippie splendor

Another achievement of The Grateful Dead was managing to endure once the counterculture of the 1960s went out of fashion. They were right at its epicenter: they played at the Monterey and Woodstock festivals and were supposed to be the band to close the ill-fated Altamont festival in December 1969, an event considered the death knell of that prodigious decade.

Their musical achievements also contributed to their survival, as Isabel Guerrero assures: “Jerry Garcia’s voice is one of my favorite male voices; I’m fascinated by its extraordinary sensitivity. You only have to listen to him on songs like Dark Star or Death Don’t Have No Mercy. Musically, they filtered American traditionalism by embracing their psychedelic zeitgeist and shaping a unique and inimitable style that has influenced countless bands to this day. And, on a personal level, unlike other artistic duos, it was important that Garcia, so druggie, modest, and playful, and Bob Weir, an Adonis on guitar, were as opposite as they were complementary, creating possible balances with the other founding members.”

The punk explosion not only didn’t end the band’s career, but it led them to one of their greatest moments of glory. In 1977, they released one of their most acclaimed albums, Terrapin Station; performed their most legendary concert at Cornell University; and broke another record at Raceway Park in New Jersey, with 107,000 paying attendees. For 47 years, it was the single-artist concert with the highest ticket sales in the U.S.

In 1981, they played the only concert of their career in Spain, at the Palacio de los Deportes de Montjuïc in Barcelona, but that was a more difficult time for the band, due to Garcia’s heroin addiction. As EL PAÍS journalist Diego A. Manrique recalled in his obituary, the band’s leader “had to face the police and an ultimatum from his bandmates, but he reacted positively and knew how to maintain his dignity in a changing world.”

The leader, increasingly weak in voice and vitality on stage, hit rock bottom in July 1986 when he fell into a diabetic coma and had to cancel all the concerts scheduled for that year. But his comeback was spectacular: their 1987 album, In The Dark, was the best-selling of their career and even put a single on the charts for the first time, Touch Of Grey.

That same year, the band toured alongside Bob Dylan, an event documented in the album Dylan & The Dead. After Garcia’s death in 1995, the surviving members tried to keep the spirit alive under various names, until June 2015, when Weir, Lesh, Hart, and Kreutzmann organized five concerts in California and Chicago. Under the title Fare Thee Well: Celebrating 50 Years of the Grateful Dead, these shows served as a final farewell and tribute to the memory of their beloved leader. Although they presented it under the band’s name, it was no longer The Grateful Dead. But their fans celebrated it as if it were..

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.