What happens when you die on the same day as John Lennon? Artists whose death was overshadowed by another

Heartfelt tributes are being paid to Kurt Cobain, who left us 30 years ago, but none to Lee Brilleaux, a British rock figure who died a few hours before him and was relegated to a footnote in an obituary

In the universe of rock fans — a place where the things that matter are being authentic, knowing more songs than anyone else, being more of a purist, and boasting about knowing a band from its beginnings, since “before they became commercial” — few events stir up the hornet’s nest more than the death of a great star. There’s the type who exaggerates his closeness to the deceased and overacts his sadness; then we have the type who claims to have always been passionate about the dearly departed’s music, even if he had never mentioned it before; finally, there is no shortage of individuals who accuse the rest of being upstarts. But there is also the fan who humbly approaches from a place of genuine curiosity, to discover the legacy of this incredibly relevant musician whose music he never had the opportunity to listen to. Looking at the bright side, this is the good part about an artist’s death: their work gets disseminated, their songs (or excerpts from their books, or scenes from their films) are shared as a tribute, attention is renewed, and sometimes they end up being more popular in death than in life.

There are those, however, who cannot even enjoy those few minutes of post mortem fame, nor do they have the opportunity to pick up new fans at the very last minute. On April 8, 1994, the body of Kurt Cobain, leader of Nirvana, was found. He had killed himself three days earlier by shooting himself in the head. His death at the age of 27, like other figures such as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison, and the elements of tragedy involved — the sadness of a very famous guy with terrible demons that tortured him, the source for sensationalism represented by his marriage to Courtney Love, his drug-fueled fatherhood and all the urban legends that originated instantly — surrounded Cobain with a mythical halo that is still in full force: tributes on the 30th anniversary of his death have not been lacking in all the main cultural outlets, and Nirvana (their songs and their t-shirts) are just as present or even more so than they were three decades ago. The same cannot be said of Lee Brilleaux, the frontman of the British band Dr. Feelgood, who died of lymphoma at the age of 41 on April 7, 1994, one day before Cobain’s death was reported.

Uncut magazine — whose April issue features on the cover an interview with the survivors of Nirvana, Dave Grohl and Krist Novoselic — regretted a few years ago, on the occasion of the publication of Brilleaux’s biography, that “Lee’s passing became a mere footnote to the unfolding drama in Seattle, briefly mentioned.” In 2015, The Guardian went further and drew an antagonism: “To blokes of a certain vintage playing in bands above pubs, he is what Cobain was to Generation X mallrats. Where Cobain created a sardonic, uninterested aura, off which slacker culture fed, Brilleaux helped kickstart British punk rock [...] Viewed today, Brilleaux is the anti-Cobain. His attitude was always one of the hard worker, a cartoon version of a hard-drinking blue-collar Canvey Island geezer. But in many ways Brilleaux was just as nonconformist and disgusted with the record industry merry go round as the Nirvana singer.”

Outlandish comparisons aside, Brilleaux was for more than 20 years the vocalist of a band that some called “the equivalent of John the Baptist” among the prophets of punk. Dr. Feelgood, founded in 1971, represented, in the progressive context, the return to the roots of rock, to primitive sounds and simple structures, which lit the fuse for the explosion of British punk. Songs like Roxette (their biggest hit), She Does It Right, Going Back Home or covers like John Lee Hooker’s Boom Boom, made up an energetic and intense songbook, with a staging that was no less impressive. Director Julien Temple, who dedicated the documentary Oil City Confidential (2009) to them, was surprised: “They were the biggest band in England for 18 months and it’s as if they had never existed.”

In the film, guitarist Wilko Johnson (who died in 2022 and who, in the headlines of many obituaries, was identified as an actor in a few episodes of Game of Thrones before being mentioned as a member of Dr. Feelgood) declared: “In rock & roll, things are as important as they are perceived, and today Dr. Feelgood is not perceived at all.” For those who did perceive the band — which is still active without any of the original members — in its golden incarnation of the 1970s, either in person or through YouTube videos, the aggressive image of Dr. Feelgood is memorable: a virtuoso guitarist, Johnson, performing an accelerated and intense blues and looking menacingly at the audience with bulging eyes, along with a singer, Brilleaux, always sweating profusely and doing push-ups live in a suit full of stains.

Josele Santiago, bandleader of Los Enemigos, does not hesitate to describe Dr. Feelgood as a “fundamental band” in his own formative years. “It was thanks to their covers that I discovered the music I love, a wide range from blues to the soul of the [record company] Stax, not forgetting New Orleans. I understood the power of simplicity, of feeling and of passion, of respect for the roots,” he says. “I was perfectly capable of hitchhiking to France just to see them.” He remembers that he found out about Billeaux’s death “in the bar downstairs” of his house. “Lee Brilleaux’s voice and his no less prodigious harmonica were perfect for this type of music. The symbiosis with Wilko’s very Martian [guitar] Telecaster, a forceful and concise rhythmic base like few others and his attitude, simultaneously humble and arrogant, was also perfect to drive the audience crazy.”

However, Santiago believes that “even if Cobain had not died, there would not have been much said about Lee. Cobain changed the lives of many people and the way they understand music. Lee was a great singer, a frontman and harmonica player, but he was a rocker and he only intended to entertain people. They cannot be compared at the level of significance. Kurt was an artist and Lee was a craftsman.”

One step away from glory

If the black masses of the Satanists are based on the parody and subversion of Christian symbols, early punk also had a lot of mocking opposition to rock: ugly and nihilistic people who allowed themselves the luxury of occupying stages and giving openly unpleasant concerts before a fervent audience, in the midst of an unintelligible hubbub of instruments. Among them, Jan Paul Beahm, singer of Germs, had a plan to become their messiah. Under the stage name Darby Crash, at the age of 17 he gave himself five years to put together a band and commit suicide at the peak of his success. With Germs, he managed to attract the attention of the specialized press and fans of the genre: they were the most attractive and scandalous group on the Los Angeles punk scene, and they were also the ones that caught the attention of director Penelope Spheeris when she made the emblematic documentary The Decline of Western Civilization (1981).

After breaking up the band, at age 22 Crash made a death pact with his girlfriend, Casey Cola, to inject themselves with $400 worth of heroin and die like legends. At the last minute, it is not clear whether out of love or egomania, the vocalist decided to give his partner a non-lethal amount so that only he would die. The ground was fertile for the Germs leader to posthumously consummate his final insult and ascend to the status of rock martyr. But a symbol of that very same hegemonic culture against which he rebelled was the one who, ironically, ruined his well-designed plan. The day Darby Crash chose to die was December 7, 1980. A few hours later, John Lennon was murdered at the entrance to the Dakota building in New York, where he lived, and the time for afterlife propaganda that Crash had hoped to obtain dwindled significantly. Kurt Cobain, who did achieve legend status after taking his own life, was a self-confessed admirer of Germs and hired their guitarist Pat Smear as a backing musician in Nirvana.

Far from the part mournful, part frivolous terrain of the great tragedies of rock, the writers Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World (1932), and C.S. Lewis, father of the Chronicles of Narnia saga (1950-56), also did not enjoy much space in the news: on November 22, 1963 it was difficult to talk about anything else beyond the assassination of U.S. president John F. Kennedy in Dallas. The death on June 5, 2004 of another former tenant of the White House, Ronald Reagan, overshadowed the death five days later of another relevant figure of his time, Ray Charles. “In line at the post office, someone asked why the flag was at half-mast. I responded that it was because of Ray Charles. “Ray was, from my point of view, a better American than Ronald,” recalled a prolific Quora user in a debate about, precisely, more and less relevant deaths.

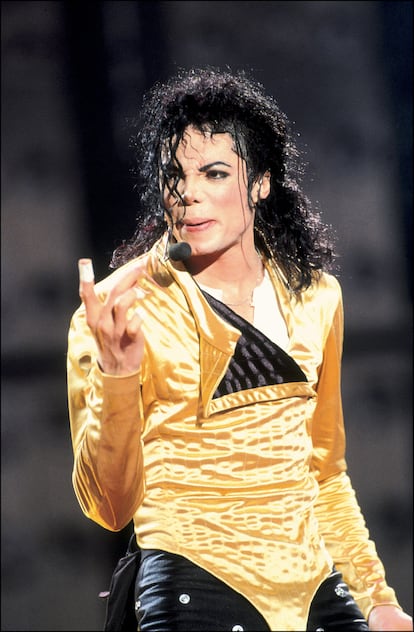

On June 25, 2009, when the death of Michael Jackson unleashed a media storm with several fronts (the lights and shadows of the deceased, the mysteries about his life, the investigation into the responsibility of his doctor in the poisoning that caused his cardiac arrest), many people failed to find out about the death of actress Farrah Fawcett, which occurred shortly before the singer’s. The news apparently did not even reach the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which in March 2010 did not include her in the Oscar tribute to the deceased of the year, unlike Jackson. The journalist Christopher Bonanos of New York Magazine proposed that the star of Charlie’s Angels was joining the “Eclipsed Celebrity Death Club.” As a paradigmatic example, he cited Groucho Marx, who died the same week in August 1977 as Elvis Presley. For a comedian who had boasted of having “worked my way up from nothing to a state of extreme poverty,” that may have been the most fitting ending of all.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.