Another surrealism existed: There were not only European men in the movement that changed the 20th century

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Surrealist manifesto, an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris proposes a new reading that broadens the role of women and non-Western voices

Europe had collapsed and a group of twenty-somethings — traumatized by World War I and alarmed by the potential for destruction that supposed “progress” implied — wanted to rebuild it. They proposed another way of seeing supposed reality, convinced that there was a truth hidden beneath the surface of the visible world. “An absolute reality, a surreality,” wrote André Breton, the movement’s leader and main theorist. Breton — who studied medicine and psychiatry, although he never completed his studies — sought to “express the real functioning of thought” and prioritize “the omnipotence of the dream.” A century after the publication of the Surrealist Manifesto (1924), the Centre Pompidou in Paris is proposing a new interpretation of this avant-garde movement, which alternated Marx’s desire to “change the world” with Rimbaud’s desire to “change life.”

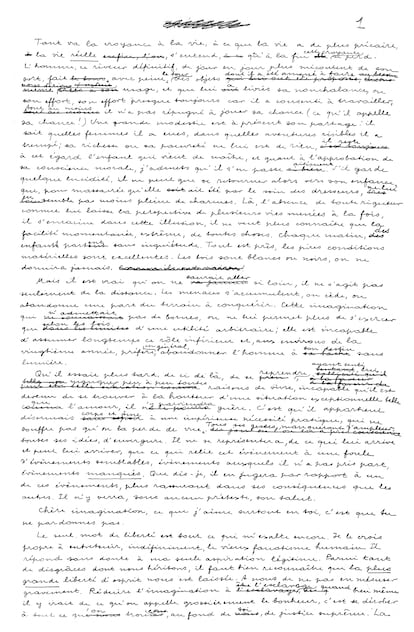

At the beginning of this ambitious exhibition — which opened this past week and will be open to the public until January 2025 — is Breton’s handwritten manifesto, bought from his heirs in 2019 by the National Library of France. It is now on loan to the Centre Pompidou. Some sentences — written in perfect handwriting — resonate in Breton’s voice, which has been reconstructed thanks to artificial intelligence. This is a questionable choice for a movement that was staunchly opposed to the industrialization and mechanization of society. The previous exhibition on this ism at the Pompidou — The Surrealist Revolution — took place in 2002. Since then, academic research has revealed new perspectives on a movement that was actually less Parisian and masculine than legend suggests. The current exhibition’s organizers admit that an update was needed.

As the Surrealism Beyond Borders exhibition — which was displayed in London and New York City in 2022 — already showed, the movement managed to go far beyond Parisian circles. It took hold in the United Kingdom, Belgium, Sweden, Italy and Spain, but also in Japan, Egypt and across Latin America. These other countries and regions are widely-represented in this new exhibition, which brings together a total of 500 artworks and documents.

“It was an international movement that spread throughout the world, free of esthetic dogmas and formalisms. It was a space of freedom and emancipation… a philosophy and a human adventure open to all those who wished to explore a new relationship with the world,” explains curator Marie Sarré. It was also “the avant-garde group that gave the most significant space” to women. Not enough space, certainly, but more than other related ideologies at the time. In the 2002 exhibition, the Centre Pompidou only exhibited the work of three female artists. In this new exhibition, nearly 40% of the selected artists are women.

The exhibition explores the dominant themes in the different surrealist schools, from the artist as medium in the work of Giorgio de Chirico and Victor Brauner, to the significant influence of Freud on the work of Salvador Dalí. The Spanish artist’s iconic painting — His Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee (1944) — has been loaned to the Centre Pompidou by the Thyssen Museum in Madrid, while the Reina Sofía has loaned The Great Masturbator (1929). The exhibit also delves into the murky eroticism of German artist Hans Bellmer’s broken dolls, to the interest in the cosmos expressed by René Magritte and Joan Miró.

The mixture of disparate elements was defined by the French poet Lautréamont as being as “beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissection table.” Over the decades, it would give rise to mixtures that were simultaneously absurd and lucid, including photo collages and exquisite depictions of cadavers. These were two of the quintessential surrealist exercises, along with Max Ernst’s frottage technique (placing a piece of paper on a structured surface and rubbing over its texture with a pencil), or Óscar Domínguez’s decalcomania, which involves pressing paint between sheets of paper.

Remedios Varo — a Mexican artist, who was never well-known in France — also has a leading role in the exhibition. The hybrid nature of the chimeras depicted in her fantastic iconography is surrealist by definition. According to popular legends, a chimera had a lion’s head, a goat’s belly and a dragon’s tail.

Surrealism was a kind of “total art” that wasn’t limited to a single discipline. It was born as a literary movement with great influence in the 20th century. Julien Gracq, Boris Vian, Julio Cortázar and even Annie Ernaux are considered to have been influenced by its esthetics. It eventually spread towards the visual arts, cinema and music, guided by that “convulsive beauty” so appreciated by Breton, who confronted the classicism of the early-20th century and managed to bury it.

Breton — known as the patriarch of surrealism — was sometimes treated as a petty dictator, who didn’t hesitate to excommunicate heretics. He pushed away several individuals from the movement, including fellow French poet Louis Aragon, Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti, as well as Max Ernst. The German artist would be expelled from the surrealist inner-circle upon accepting a prize at the Venice Biennale in 1954, a sacrilege for Breton. However, through the exhibition, Breton is somewhat rehabilitated. Those responsible for it present him as an upright leader who opposed the commercialization of art and gregarious submission to political parties. “In surrealism, the artist had to be politicized, but not his art,” the curator confirms.

One of the most striking rooms is dedicated to the figure of the monster, which symbolized the political and social ills of the time. Max Ernst’s painting L’ange du foyer (1937) — translated as The Fireside Angel, or The Triumph of Surrealism — seems to foreshadow the horrors that Europe would face a few months later. On a different scale, Dorothea Tanning — who would later marry Ernst — spoke of other monstrous figures in her installations, which seem to be possessed by sexual ghosts and childhood memories in an ominous domestic environment. The scenes — oftentimes covered in dust — are ones in which terrible events undoubtedly took place.

Ernst and Tanning are two of the surrealist icons that are highlighted by the exhibition. Other popular paintings and figures — such as Man Ray and Dora Maar — are also included, but they are counterbalanced with less-known names. For example, there’s Unica Zürn — author Hans Bellmer’s wife, who painted delicate, oceanic-inspired landscapes — or Ithell Colquhoun, a British woman born in colonial India, who created several hallucinatory landscapes. In 1940, Colquhoun was excluded from the surrealism group, due to her esoteric affiliations and her practice of the occult. Tate Britain — formerly known as the Tate Gallery — will dedicate a retrospective to her in London next year.

At another point in a journey full of unexpected ideas, a small series of paintings by Caspar David Friedrich recalls the movement’s link to German Romanticism and its obsession with nature and the forest, which reached the jungles depicted by the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam, who has two works on display in the Paris exhibition.

In other rooms — half-hidden — there’s a work by Victor Hugo and another by Odilon Redon, as if suggesting that these men were the putative fathers of this movement. And then, there were other surrealists avant la lettre claimed by its members. In general, these were heretical figures, such as the Marquis de Sade and Rimbaud, or lesser ones, such as Lewis Carroll, the more decadent Joris-Karl Huysmans, or a precursor of the absurd, like dramatist Alfred Jarry.

The exhibition greets visitors in the form of a labyrinth, one of the surrealist tropes par excellence. It delves into the complexity of a movement that — despite having dissolved itself in 1969 — remains very present in contemporary culture. The stereotypes that tarnished its name — such as a link to kitsch, which didn’t always seem justified — have disappeared. “Surrealism isn’t dead… at least, not as a way of thinking,” says Jean-Claude Silbermann, who at 89-years-old is the last living member of the surrealist group, on the eve of the exhibition’s opening.

The artist was finishing the installation of a series inspired by Alice in Wonderland, alongside a work by British-Mexican painter Leonora Carrington: a self-portrait in a straitjacket that recalls her difficult days in a psychiatric hospital. Following the unexpected return of figuration as the predominant language in art, today’s artists are — once again — defending the teachings of surrealism, the power of the marvelous and the poetic as weapons for surviving in a world that’s adrift. “It’s no coincidence that all of this is happening in times of political turbulence and amidst the new rise of nationalism,” says curator Marie Sarré. After all, the same thing happened about a century ago.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.