The trail of Nazis Mengele and Eichmann in Argentina

The Milei government has published online declassified files on the activities of war criminals in the country

On June 22, 1949, Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele arrived at the port of Buenos Aires in search of impunity. Known as “The Angel of Death” for murdering thousands and conducting grotesque experiments at the Auschwitz concentration camp, Mengele entered Argentina using a false passport under the name Helmut Gregor. He was 38 years old and claimed to be a “mechanical technician” looking to begin a new life far from his country after World War II. He felt so secure that, six years later, he applied for new documentation under his real name and remained in Buenos Aires until the arrest of fellow Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann by Israeli secret services.

The movements of Mengele, Eichmann, and other high-ranking members of Hitler’s regime in Argentina can now be traced thanks to a trove of declassified documents recently published online by Argentina’s National Archive (AGN).

The collection, comprising nearly 2,000 documents, was originally declassified in 1992 but could only be consulted in person at the AGN. On Monday, President Javier Milei’s government announced it would make the materials publicly accessible, following the delivery of a copy to the Simon Wiesenthal Center, which is currently investigating Credit Suisse’s alleged ties to Nazism. “[The Argentine state] has no reason to continue safeguarding this information,” said Chief of Staff Guillermo Francos during the announcement.

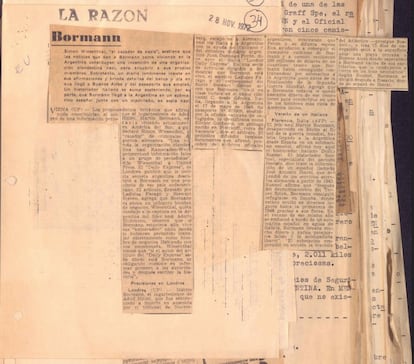

Hitler’s private secretary, Martin Bormann, arrived in Argentina in 1948, followed by Mengele in 1949 and Adolf Eichmann — one of the chief architects of the Holocaust — in 1950. All three fled Europe via the so-called “Ratlines” — clandestine escape routes used by Nazi fugitives — and settled in Argentina, which at the time was governed by Juan Domingo Perón.

From refuge to extradition

According to Ariel Gelblung, director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, the newly released archives may not provide new information for experts, but will allow all interested parties to examine original sources and draw their own conclusions about the years when Argentina served as a sanctuary for fugitive war criminals. “This shows how Argentina’s position on this issue in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s was very different from what it was after the return of democracy in 1983, when all the war criminals found were extradited.”

The initial impunity is evident when looking at the official documents. Mengele’s police record shows that on November 26, 1956, he applied for a new national identity document as Jose Mengele, “a manufacturer by profession,” “in connection with the rectification of his first and last name.” With his true identity restored, he crossed into Uruguay to marry his brother’s widow, and the two returned to live in Argentina.

The earliest official documents on this Nazi war criminal do not reveal any awareness of his past — something that did not surprise experts. However, later intelligence reports include publications describing Mengele as “a monster of Auschwitz.” One such report is a 1959 article from The Jerusalem Post, which states that the crimes attributed to Mengele include “the selection of Jewish prisoners sent to him for medical experiments followed by death in gas chambers,” “the personal killing of Jewish prisoners by phenol injections,” “throwing newborns into fire in front of their mothers,” and “the murder of a 14-year-old girl with a knife.”

The files on other Nazi criminals are similar, and include articles from foreign newspapers detailing the crimes committed and the locations where these individuals were allegedly hiding, as well as telegrams and correspondence between national and international agencies.

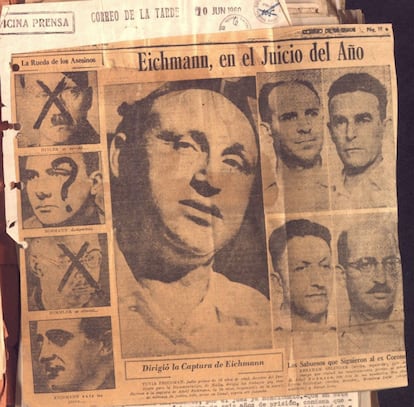

Adolf Eichmann, head of Hitler’s Office of Jewish Affairs, used a passport issued by the Red Cross to enter Argentina in 1950 under the alias Ricardo Klement, a stateless technician supposedly born in the Italian city of Bolzano. He lived for years in a house in San Fernando, a city north of Buenos Aires.

The high-ranking Nazi officer never suspected he had been discovered and was being surveilled by 11 Israeli agents led by Isser Harel, who oversaw the team that abducted Eichmann as he stepped off a bus on May 11, 1960. According to the declassified documents, the operation received assistance from members of Argentina’s security forces.

Nine days later, Mossad agents sedated him, dressed him as an airline pilot, and smuggled him onto a flight bound for Tel Aviv. Upon arrival, Harel called then-Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion. “I have a gift for you,” he said. Two years later, on May 31, 1962, after being found guilty of crimes against humanity, Eichmann was executed by hanging.

As the net tightened, Mengele fled first to Paraguay and then crossed into Brazil, where he drowned in 1979 under the alias Wolfgang Gerhard. The truth did not come to light until 1985.

Support networks

Nazi war criminals reached Argentina thanks to an international network that provided them with false passports and helped them settle within the country’s borders and remain undetected — Mengele’s case being a prime example. The doctor first stayed in a Buenos Aires hotel, then moved into the home of Gerhard Malbranc, one of the frontmen managing Nazi funds.

The path of those funds — allegedly stolen from Jews, sent to Argentina to finance pro-Nazi businessmen, and partly returned to Europe through the bank known today as Credit Suisse — is still unclear. It is the subject of an investigation, on which the Simón Wiesenthal Center hopes to have news “between February and March of next year,” according to Gelblung.

“These accounts ranged from German companies such as IG Farben [the supplier of Zyklon-B gas, used to exterminate Jews and other victims of Nazism] to financial institutions such as the German Transatlantic Bank and the German Bank of South America. These two banks apparently served as transfer channels for Nazis en route to Switzerland,” the Simón Wiesenthal Center told EL PAÍS when the investigation began in 2020.

Some Nazi leaders, such as SS Captain Erich Priebke, managed to live in Argentina undisturbed even after the country’s return to democracy. Priebke settled in the Patagonian city of Bariloche and remained under the radar of justice until 1991, when he was interviewed by Argentine writer Esteban Buch and spoke openly about his role in the Ardeatine Caves massacre, where 335 Italians were executed on Hitler’s orders. Three years later, when a team from the U.S. network ABC returned to interview him, the footage made global headlines and prompted widespread calls for his extradition to Italy. Priebke was sent to Rome, tried, and sentenced to life imprisonment for his crimes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.