A Bavarian enclave in Brazil protected Mengele even after his death

A new book tells the story of two German-speaking immigrant families and a fervent Nazi who continued to keep the Angel of Death’s secrets even after he drowned in São Paulo

In April 1979, Gregory Peck was nominated for an Oscar for his powerful portrayal of the sadistic Nazi criminal, Dr. Josef Mengele. Although he didn’t win, Peck’s performance in The Boys from Brazil transformed Mengele from a cruel doctor in black and white photos, known for his horrifying experiments on twins in the Auschwitz death camp, into a fugitive who captured the public’s imagination. He was now a man in an immaculate white suit and a Panama hat, who lived in a jungle mansion somewhere in Brazil. At the time, Mengele’s whereabouts were still unknown, but the film got it right. As it turned out, Mengele was indeed in Brazil, but he was long gone — dead and buried.

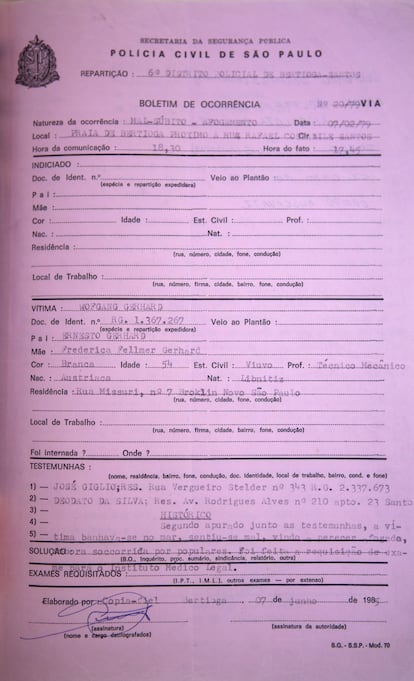

Two months prior to the Oscar ceremony in Hollywood, the world’s most sought-after Nazi perished at the age of 67 on Bertioga beach, near São Paulo. Mengele was enjoying an outing with close friends, Liselotte and Wolfram Bossert. Their children — Andreas and Sabine — didn’t know Mengele was a notorious Nazi doctor. They knew him as Uncle Peter, who had shared countless swims, canoeing adventures, countryside trips, and steak meals with them. This intimate circle of trusted friends played a crucial role in hiding the fugitive from the relentless Nazi hunters who pursued him.

Brazilian journalist Betina Anton’s book Baviera Tropical (Tropical Bavaria) reconstructs the escape from Germany of Josef Mengele, Auschwitz’s Angel of Death, and how a handful of close friends protected him for two decades in Brazil. European expatriates were aware of his secret, yet never betrayed him, despite a 1959 arrest warrant offering a $3.7 million reward. Mengele evaded discovery and justice for 34 years, first escaping from the Nazi death camp in Poland to his native Bavaria, then moving through Argentina and Paraguay, before settling in Brazil.

Anton, a journalist and international news editor for the Globo TV network, thoroughly covers Mengele’s time in Brazil. His initial contact was an Austrian man named Wolfgang Gerhard, who let Mengele use his name and Brazilian documentation. In fact, that was the name on Mengele’s death certificate and tombstone in the Embu das Artes cemetery near São Paulo. “Gerhard was a fervent Nazi who placed swastikas atop the family’s Christmas trees. He introduced Mengele to other sympathetic families in the area,” said Anton.

“Mengele lived here for almost 20 years because he was protected by friends. There was an Austrian couple [the Bosserts] and a Hungarian couple [the Stammers]… They all spoke German, so [Mengele] could converse with them in his own language. He didn’t end up in some remote corner of the world and lose touch with his culture. No, he lived in a tropical Bavaria where he listened to classical music and had a library of up-to-date German books.” He also corresponded regularly with his only son, Rolf, and with other close friends in Germany. And his family never stopped sending him money from home.

When Anton was six years old in the 1980s, she met one of the people from Mengele’s close circle of friends. Liselotte Bossert was a teacher at Anton’s school for the German community in São Paulo. One day, she disappeared from school and never came back. The serious expressions and hushed conversations of the adults told Anton that something serious had happened. This was Anton’s first encounter with the chilling story that she spent six years investigating, conducting interviews and immersing herself in the Nazi doctor’s letters.

Gerhard protected Mengele for ideological reasons. “But the Stammers weren’t Nazis, they actually came to Brazil to escape communism. The Federal Police found out that they had some kind of business with Mengele, who even helped them buy a farm [where they all lived together]. Gitta Stammer was the one who brought him money every week,” said Anton. Liselotte Bossert’s husband had been a corporal in the German army and had enormous admiration for Mengele. And Liselotte? “I think she acted out of friendship and didn’t want to believe the crimes he committed. He always said he was a scientist. And her children became very attached to Mengele.” Bossert’s children refused to be interviewed for Anton’s book.

Anton was able to interview Rafi Eitan, the former head of Israel’s Mossad who is now in his nineties. Eitan was part of the team that tracked down Adolf Eichmann in Argentina in May 1960 and brought him to Jerusalem to face trial. That’s when they discovered a clue that led Israeli Nazi hunters to São Paulo. “Rafi Eitan told me that he once met Mengele face to face, but they couldn’t grab him right then.” Soon after, Israel became embroiled in a crisis with Egypt, so Mossad’s pursuit of Nazis had to take a backseat.

Cyrla Gewertz was a victim of the Angel of Death’s experiments in Auschwitz. He would immerse the young Polish girl in very hot water for 15 minutes, and then dunk her for 15 minutes in ice water. And so on, all day long. When she cried out that the water was burning her, the Nazi snapped: “Put your head under or I’ll kill you.” Another human guinea pig died right next to her.

Many years later, Gewertz was married to another Holocaust survivor and living in São Paulo when someone approached her at a hotel in the nearby city of Serra Negra. “Do you know who’s living here? Mengele!” Gewertz was petrified. “She packed her things and left immediately,” said Anton. “She was so traumatized that she didn’t ask questions or call the police. When I interviewed her [in 2017], she told me she still had trouble sleeping and cried easily.”

A symbolic trial in the 1980s

In 1985, during the 40th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, Mengele’s victims reminded the world about his cruel crimes. Led by Eva Mozes Kor, they conducted a symbolic trial in Jerusalem, where numerous twins shared testimonies of the atrocities. These testimonies were televised worldwide, including in Brazil, resulting in joint efforts by West Germany, Israel and the United States to locate Mengele.

The crucial clue came from a German who told the police about a drunk guy who boasted that he was sending money to the Angel of Death in South America. The drunk turned out to be a Mengele family courier. When investigators followed the clue, they learned that the world’s most-wanted Nazi had drowned six years earlier in Brazil. They found the Stammers and the Bosserts, who confessed their roles under interrogation.

Liselotte Bossert was fired from the school where she taught, while Brazil and the world watched as Mengele’s body was exhumed and tested to confirm his identity. Mengele’s victims found some relief in knowing that their torturer was finally dead. No documentation of his experiments has ever been found to help doctors treat the never-ending health problems of the victims who survived.

The remains of the infamous and sadistic Nazi doctor ended up in the University of São Paulo’s medical school as educational material for students.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.